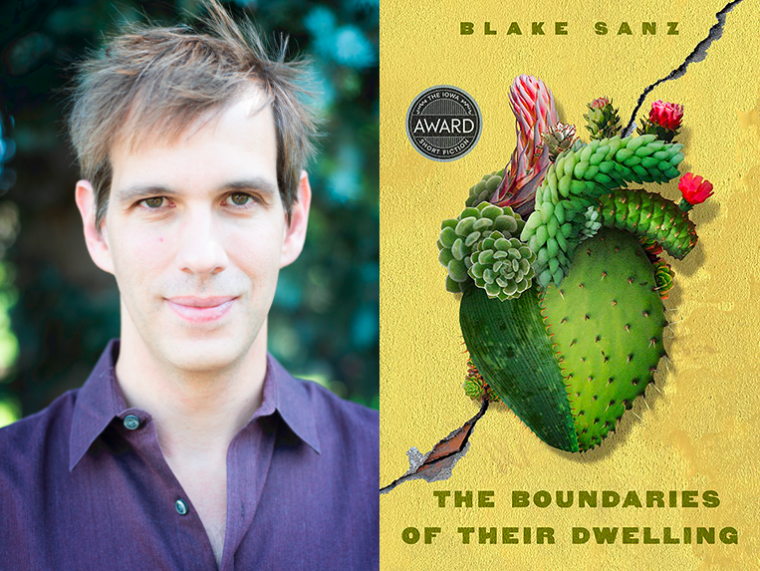

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Blake Sanz, whose debut story collection, The Boundaries of Their Dwelling, will be published on October 15 by the University of Iowa Press. Throughout The Boundaries of Their Dwelling, Sanz demonstrates remarkable tonal range, even within individual stories. In the first story, “¡Hablamos!,” two teenagers, Emi and Frida, arrive in Miami from Mexico to film a talk show, but while they revel in the glitz of travel and TV, an incident of violence forces them to slow down and tend to each other. In one particularly moving sequence, Emi describes gently maneuvering out from under Frida, who has fallen asleep in her lap while watching a movie. As the collection unfolds, shifting between Mexico and the southern U.S., Sanz remains this attuned to the ever-evolving dynamics between his characters—and between characters and places. “The characters in these stories are not lifelike so much as they are alive, rendered warm-blooded and human by Sanz’s pitch-perfect details and lucid prose,” writes Brandon Taylor, who selected the manuscript as the winner of the Iowa Short Fiction Award. “It’s a riotous collection of stories that together capture the tumult of what it means to be alive.” Blake Sanz’s writing can also be found in Ecotone, Puerto del Sol, and Fifth Wednesday Journal, among other publications. A graduate of the MFA program at Notre Dame, he lives in Colorado and teaches writing at the University of Denver.

Blake Sanz, author of The Boundaries of Their Dwelling. (Credit: Manuel Bleakley)

1. How long did it take you to write The Boundaries of Their Dwelling?

One answer is that I wrote the oldest story that appears in the book in 2001, and I finished with copy edits this June—so, twenty years.

Another answer is that, most of the time that I was writing these stories, I didn’t yet view them as a collection. I only got to that stage around 2016, at which point I went back and revised to make the stories work together. So maybe it was four or five years?

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Aside from the self-doubt of swimming blind for so long, the hardest part was deciding what stories would appear in the collection and in what order. It took rereading Jhumpa Lahiri’s Unaccustomed Earth to see a structure that I might use as a starting point for my own curation and arrangement. Once I decided on that, I saw how I might go from an unwieldy pile of stories to a cohesive and intentional collection.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I like public places where it’s socially acceptable to be alone with a laptop. I don’t drink coffee, though, so cafés are out. Denver has lots of markets with common areas where you don’t have to buy things—Union Station, Denver Central Market, Junction—so that’s been my staple. When there’s not a pandemic, I also love writing on public transportation. There’s something about writing a scene while you’re literally going somewhere. I rarely write at home.

As for the when, my writing is seasonal. Since I teach at a university with a quarter system, we get December free, and I write a whole lot then and also in the summer. In those periods I often write or edit—which occasionally just means rereading my own words and sighing—for five to six hours a day. During the academic terms—from September to November and January to June—I take notes about edits, and the writing’s with me in spirit, but that’s usually my time to let drafts simmer. I like the pressure that comes with summer writing and the room to breathe that the school year affords.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just finished The Foreign Student by Susan Choi. My god. So far I’m loving Lorraine López’s Homicide Survivors Picnic and Other Stories. The consciousnesses dramatized in both of these books—they feel to me like kindred spirits.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Valerie Sayers. She’s written six novels and a book of stories. She’s funny and philosophical and poignant and I love her blend of New York and low country South Carolina. Maybe start with Brain Fever?

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Self-doubt. More specifically: dithering between the sense that I’m done with a project versus the dread that years of work might still remain before that project is ready. Looking back I realize that I’d set the final form of The Boundaries of Their Dwelling many years before I submitted it anywhere, and I wish now that I’d sent it out earlier. Conversely I’ve submitted “finished” novels to agents that, in retrospect, clearly weren’t ready. How does anyone really know either way?

7. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Yes, maybe. If you can get funding. But live a little first. I made a mistake by going straight into an MFA out of my undergrad. I wasn’t ready to take it as seriously as I might have, and I didn’t have much to write about yet. My experience was a great one, though, and it did help me land a teaching job, but I think I would’ve gotten more out of that degree at an older age.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Boundaries of Their Dwelling, what would you say?

Trust yourself and your own vision for your work. Stop revising a story after every rejection. Seek out others you can trade work with. Maintain those relationships. Develop thicker skin more quickly.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

Outside of my partner—who’s great as both a line editor and a person who asks insightful, bigger-picture questions—I don’t have one. Anyone interested? This is mostly my own fault. I should’ve been more intentional about cultivating these relationships over time, but I wasn’t, and so, when I have a draft ready for feedback, I track down writer friends and offer a swap. Which works well enough, but I do envy those writers who mention having had the same trusted readers across years and decades.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

For those at MFA programs, I’ll offer this: At Squaw Valley, Greg Spatz told us that 90 percent of what you hear about your writing in workshop is probably not useful, but that this doesn’t invalidate the process. The real work is to figure out what advice falls into the other 10 percent and what to do with it once you identify it.

I’m cheating now, but here’s a second pair of suggestions at odds with each other that I find useful to hold in tandem: At Napa Valley, Sam Chang emphasized the importance, for novel writers, of just getting through a first draft, in the vein of Anne Lamott’s “shitty first draft” advice. For certain of us, this can be invaluable. But then there’s Zadie Smith’s alternate take that you might be best served by drilling down into the language of your first pages, agonizing over them incessantly until the voice and cadences are just right, and after you’ve got them perfectly set, then moving quickly forward with the rest.

One could easily read these conflicting suggestions with frustration, but I like the idea that there are brilliant writers who take different approaches. My sense is that I’m better off holding multiple possibilities in my head for a way forward. It helps me feel that, whichever way I go, there’s reason to believe it can work.