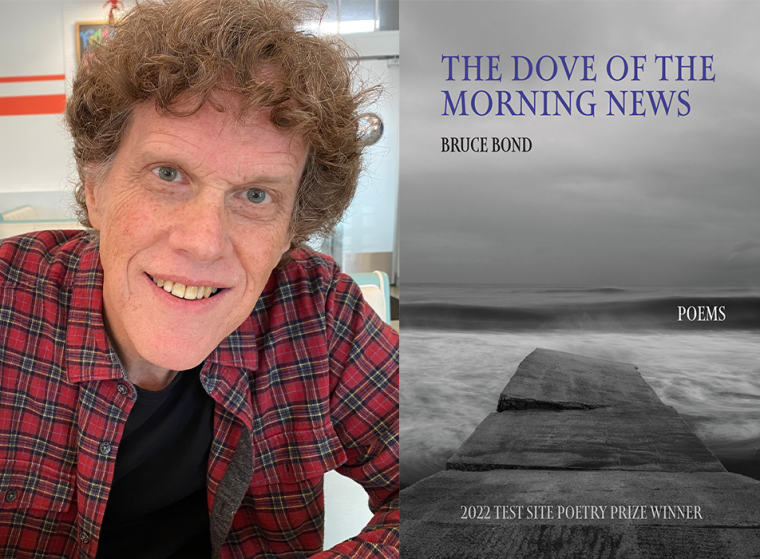

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Bruce Bond, whose poetry collection The Dove of the Morning News is out today from the University of Nevada Press. The poems in The Dove of the Morning News are both personal and historical, interrogating tribalism and systemic cruelty as rooted in shame, dread, and insecurity. The title sequence interrogates the vision of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, whose view of an increasingly interconnected cultural conversation can now be understood as a premonition of the internet. Claudia Keelan said, “The best book in the many written by one of the best living American poets, The Dove of the Morning News is news that will stay news.” Bruce Bond is the author of thirty-five books, including Patmos (University of Massachusetts Press, 2021), Behemoth (Encounter Books, 2021), and Liberation of Dissonance (Schaffner Press, 2022), plus two books of criticism: Immanent Distance (University of Michigan Press, 2015) and Plurality and the Poetics of Self (Palgrave Pivot, 2019). He has received numerous honors, including the Juniper Prize, the Elixir Press Poetry Award, the New Criterion Prize, two Texas Institute of Letters Best Book of Poetry awards, a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, and seven appearances in Best American Poetry. Bond teaches part-time as a Regents Emeritus Professor of English at the University of North Texas.

Bruce Bond, author of The Dove of the Morning News. (Credit: Nicki Cohen)

1. How long did it take you to write The Dove of the Morning News?

I don’t know exactly, since I tend to work on several books at a time, but my guess is four or five years. In my work I try to engage the immediacies of the cultural and the personal, and labor, best I can, to listen for the missing voice in any given conversation, any text, including my own. The oldest of the four poems in the book (a sequence “Vellum” about “writing across people’s bodies”) was written during the first Trump administration but before the pandemic. The spring of 2020 I wrote the title sequence that engages the thought of Teilhard de Chardin, the philosopher and theologian who is credited with predicting the internet and a heightened sense of global connectivity. A bit later I wrote the remaining poems (“Imperium” and “Cross”) that investigate tribalism and systemic cruelty, their roots in individual psychology, and their role in group-narcissism and self-deception.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I love lyric speculation, always have, but it has particular challenges. Blake is helpful, his notion that the fall shattered human character into four Zoas: the heart, the mind, the body, and the imagination; and the imagination brings the other Zoas into greater communion. The Zoa that I find most enervated in contemporary culture, in light of the internet and the opportunistic exploitation of rage, is that of “thinking.” So it feels healing to honor the power of thought as dynamic, evolving and, paradoxically, key to kindness. But one of the hardest things to do in a poem is to develop thought without lapsing cold, pedantic, overly directive. My solution is not simply to make the poems more personal, although I do that in places. I value imaginative play as a form of inquiry. I still think surrealism (the tension between reflection and dream) has a lot of untapped potential as a progressively thoughtful medium—something less prone to metaphorical scatter or the fetishization of the odd. Beyond this, “thought” is more than rationality alone. It includes acts of attention (ontology), what we might call “mindfulness” or “vision” (the root of the word “idea” is “something seen”). Like many other poets I love, I often think with the image, as an instrument of seeing as opposed to an illustration. It’s a way of thinking with the heart, feeling with the mind. Yes, I want, as Dickinson says, for the poem to take off the top of a reader’s head. But I also want the head to fill with light. That said, I never feel I’m done with a poem until there is something in it that I don’t completely understand. I think of good poems as making their failures known, evoking something of the surplus beyond the reach of words.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I try to maintain a daily discipline of reading and writing. I am fortunate in that it is very easy for me to focus for long or short periods of time. I can write most any time, any place.

4. What are you reading right now?

I am reading poems by my old teacher, Bert Meyers, a surrealist who died in 1979. A new volume of his work is now available as a part of the Unsung Masters series. Marvelous. Also, Iris Murdoch and Dostoyevsky.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

So very many, it’s hard to pick just one. Certainly the philosophers Anna Kornbluh, Byung-Chul Han, Emmanuel Levinas, and Michael Thompson—writers who shed critical light on our current cultural situation. The poems of Kathleen Graber, Virginia Konchan, John Amen, Mary Ann Samyn, Dan Beachy-Quick, and Shane McCrae also come to mind. The poetry I hold close embodies a spirit of interiority, interrogation, and lingering—what Byung-Chul Han associates with a much-needed “negativity.” I realize many see “interiority” as regressive and politically disengaged. I feel just the opposite. Interiority is, of course, never absolute. Moreover it is highly political in ways never more apparent than in our own time, since it challenges, investigates, and destabilizes categories deployed as instruments of exploitation and self-promotion. The best poetry resists exhibitionism, mob-consciousness, and a thought-enervated presentation of surfaces.

6. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I wanted to start with “Imperium” because it sets the stage for the other work. The opening of the poem explores cartooning (or “animation”) as a metaphor for how one goes about imagining other people. We create fictional characters all the time, avatars in our minds, particularly but not exclusively of groups, and most problematically, of antagonists. Those with weaker egos incapable of a genuine relation are particularly susceptible. The book then goes deeper into the individual psychology involved when cruelty becomes systemic. I say this, but I should emphasize that I want the book to be a pleasure to read, in spite and in light of the elements of seriousness and emotional difficulty. Also I want the daily and intimate to coexist with the historical and cultural. Equally important: imaginative play. So the organization evolved often with me writing something and then asking, okay, what did I leave out? What is the next needful thing? Also, the book consists primarily of long sequences made up of shorter lyrics, so the satisfaction of resonant silence comes often, in collaboration with the depth of a sustained engagement. This helps lighten the feeling of the book while accommodating long forms. The meditation on Teilhard de Chardin and global connectivity makes for the most developed of all the meditations, and given its scope and subject matter, it felt like a fitting last gesture, like the final movement in a symphony.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

I have a wonderful relationship with my editors, but I have rarely heard much in terms of editorial suggestions. I can’t recall any with this book. I should say, in gratitude, that I was wonderfully surprised by both the cover of the book and the endorsements I received, neither of which I had a hand in soliciting or acquiring. The fact that Donald Revell noted my consideration of contemporary peril in terms that transcend our time means a lot to me. Yes, that’s my aspiration. I want to write poems that stay relevant.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Dove of the Morning News, what would you say?

First one step, then another. The art of poetry is the art of priorities. Every decision you make in a poem, no matter how funny or small, says something about what you value. All good poems are love poems.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of The Dove of the Morning News?

Teaching. And working in a university. You learn a lot about love, anxiety, transference, and the quest for meaning. The class I teach now is one of my very favorites.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I received two pieces of advice that helped me a lot. Donald Revell told me to not think so much, and Robert Pinsky told me to think harder. They were both right. As T. S. Eliot said, “The bad poet is usually unconscious where he ought to be conscious, and conscious where he ought to be unconscious.”