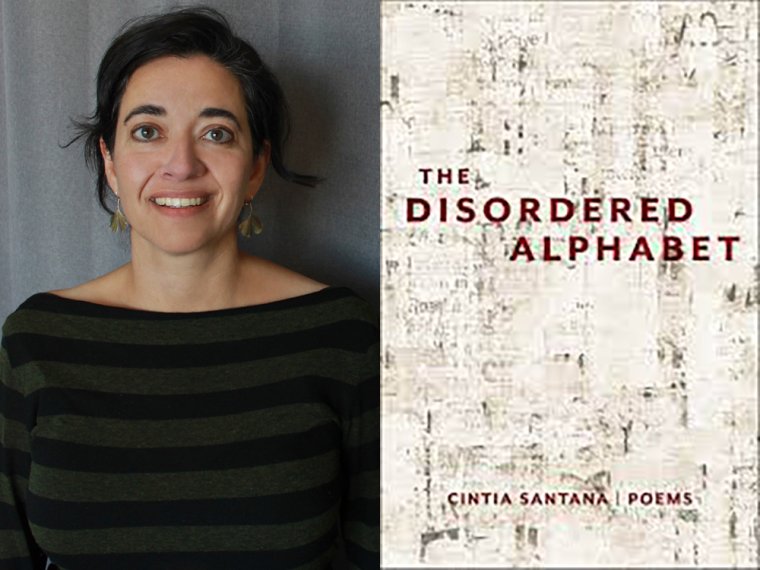

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Cintia Santana, whose debut poetry collection, The Disordered Alphabet, is out now from Four Way Books. This engaging and surprising book interrogates language in quite literal terms, with epistolary poems addressed to specific letters of the Roman alphabet. In free verse and more experimental forms, these poems whirl down and across the page, accumulating meaning through sonic play and free association. Densely packed and ecstatic, the lines at times call to mind the spring-loaded articulations of nineteenth century Anglican poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, particularly when read aloud: “Held / heart / holed / whole. / Harpooned. / Heart on / but hard. / Hell / in a hand. / With harps. // Hark! I said / Hear me,” Santana writes in “[H].” The letter poems are interspersed with self-portraits, elegies, and other meditations all in conversation with the collection’s overarching inquiry into the nature and efficacy of verbal expression. Ross Gay praises the collection: “The Disordered Alphabet tussles with diction, wrangles with syntax, struggles with the sentence and the line in a kind of linguistic unmaking that somehow becomes a beautiful, unsettling song.” Santana teaches fiction and poetry workshops in Spanish as well as literary translation courses at Stanford University. Her work has appeared in the Kenyon Review, Narrative, Pleiades, the Threepenny Review, and elsewhere. Her work has been supported by CantoMundo and the Djerassi Resident Artists Program.

Cintia Santana, author of The Disordered Alphabet. (Credit: Rewa Bush)

1. How long did it take you to write The Disordered Alphabet?

Somewhere between five and fifteen years. The idea to write a letter addressed to each letter of the Roman alphabet came to me in the spring of 2013, and I was sending out the manuscript by 2018. But the oldest poem in the book is an abecedarian about mushrooms that I wrote in 2007. And the newest is a complete rewrite of my poem to the letter M undertaken in 2022, long after I had turned in the “final” version of the manuscript.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Revisiting the grief that preceded the writing of the poems. That was hard but also necessary. Like many writers, I process the world most deeply through words. For me, giving language to something, finding a name for it, enacts a kind of metabolic process.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

It depends on the season. The reading and writing I do during the academic year is primarily in support of my teaching. I generate most of my poems in the summer, at the workshops offered by Kenyon Review, Napa Valley Writers, and the Community of Writers. It turns out that I write well under overnight pressure. During the school year I revise and send out work I’ve written in the summer. But in some ways I’m always writing. I carry a notebook in which I write down images, ideas, scraps of language, phrases, even solitary words. As I tell my students, poetry is everywhere—you just have to pay attention.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m currently rereading a couple of things. Hugh Raffles’s poetic and encyclopedic The Book of Unconformities: Speculations on Lost Time, a book that came to my attention early in the pandemic, thanks to a beautifully written New York Times review by Parul Sehgal. I’m also rereading Translation Zone, winner of the 2022 Marsh Hawk Press Poetry Prize. It’s a first book by a friend, Brian Cochran. His poems are these acts of emotional and linguistic magic. I’ve been his fan for a long time, and over the last few years his work has reached a level such that I’m always asking myself after reading a poem, “How did he get there?” I also just returned from CDMX, where I did some catching up on contemporary Mexican poetry—recent works by Sara Uribe, Tedi López Mills, Eva Castañeda, and Elisa Díaz Castelo.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

As you might imagine, titling my collection The Disordered Alphabet was of no help. I knew there was an emotional arc to the process of grief, but I also knew it wasn’t linear. I felt the first two sections needed to begin with the speaker’s various losses and a subsequent grief that could not easily be named nor voiced. The third and last section revealed itself more slowly; poems that reflect a wider view of lived experience, of the stunning beauty of the world that persists, that insists even, under the eaves of loss. Or is sharpened precisely because of loss.

Ordering the poems within those sections was harder. I had heard a good rule of thumb was to order poems in such a way that each one could be entered into more deeply as a result of the ones that preceded it. At a CantoMundo retreat, Andrés Cerpa gave me the best general advice that I think I’ve received: to read all the poems out loud, even record them, and listen with an ear for tone.

Eventually I covered my living room floor with all my poems and moved them around a bit every day or two. Standing over them one day, I realized that, of course, there was no one best order. Many compelling orders exist. I think that holds true for most manuscripts.

6. How did you arrive at the title The Disordered Alphabet for this collection?

It could be said that the title goes back to my childhood. I mostly grew up in California, but Spanish is my first language. A short while before I was to enter kindergarten, when I knew no English whatsoever, my parents sat me down in front of the TV to watch Sesame Street. They felt that I could learn some English in this way, including my ABCs. My father helped me practice because I would need to recite them soon for a teacher to decide if I was ready for kindergarten or not. No pressure for a five-year-old, right?

When the day of truth arrived, I started off quite confidently—before faltering somewhere around M or N. At that moment stumbling over the very atoms of language felt highly consequential. Somehow, nonetheless, I was allowed to begin an illustrious kindergarten career. Fast forward to reading a lot of Borges.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of The Disordered Alphabet?

The day the letter R wrote me a letter! In the spring of 2013, I was grieving two losses that had occurred very close in time. I was angry. I wanted to take “God” to task. So one day I wrote a poem, a letter to the letter A that began, “You are the Alpha and the asshole. The ass of the assassin. Yet I await you in the artic, anorak and all. Astound me. Anchor my ache and astound me now.” Like I said, I was angry. And I also felt in need of some kind of mercy. The A poem that’s in the book has no trace of this first draft, but that’s how I began to write my letters to the alphabet. I was trying to make sense of life’s “grammar,” a grammar filled with oddities and exceptions, that had become increasingly difficult to parse.

Epistolary writing felt like a fitting form, as it also implies someone distant or absent. In the U.S., grief is a party of one. It’s an experience that feels particularly invisible, silent, and silenced. So how can we—how do we— give voice to our grief? With whom do we speak of it? How can the unspeakable be spoken, be given form? The Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro says, “the poet is a small god.” In The Disordered Alphabet I think of the letters that the speaker addresses as major gods, divine and indeterminate. Much like language or a divine power, the Roman letters are insufficient—to be implored yet remaining distant. The epistolary form allowed me to voice questions about grief while telling it slant.

As I was finishing the manuscript, I decided the first iteration of my R poem needed a complete rewrite. And that’s when R started to write me a letter. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised, but it was really something. Suddenly I was thrown into a different vantage point: What would a god-letter have to say back to the grieving speaker?

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Disordered Alphabet, what would you say?

Don’t be afraid of silence. Silence, which manifests at times as writer’s block, scares me. There’s a poem, “Mr. Vastness and Mr. School Answer My Letter,” in which I found my way to the line, “be not deceived, Sister of Lazarus, / by silence, spring of speech.” It’s easy for me to forget that silence is often a time of great gestation. It’s important to observe it—by which I mean not only noting it but also honoring it by giving it the space to be. It’s the urge to fill it, rather than the silence itself, that often proves excruciating.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I did a fair bit of research on the atomic bomb and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. My husband, Hideo, is—conveniently—a physicist, and I would sometimes ask him, “Can I say this? Is this counterfactual in some way?”

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

As an undergraduate I was enrolled in a fiction workshop in which we read Ted Solotaroff’s essay “Writing in the Cold: The First Ten Years.” Solotaroff had discovered many young, gifted writers during his time as editor of the New American Review. But ten years later he saw that half of those promising writers had all but disappeared. Solotaroff determined that talent wasn’t the deciding factor. Instead he saw persistence as the defining difference—persistence despite the many hurdles (including economic) the work of writing entails. Solotaroff states, “For the gifted writer, durability seems to be directly connected to how one deals effectively with uncertainty, rejection, and disappointment, from within as well as from without. . . .” With that in mind, I promised myself that I would still be writing—no matter what—ten years out. Life has brought many interruptions, many distractions, and the writing years have hardly been even, but I have continued to write. Some years that’s meant little more than scratching down things in a notebook with little or no “finished” anything. But I’ve kept my promise to myself: I have continued to write ten years out—and then some.