This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Claudia Acevedo-Quiñones, whose debut, The Hurricane Book: A Lyric History, is out today from Rose Metal Press. In this hybrid collection of essays, poetry, documents, and other text, Acevedo-Quiñones weaves personal narrative with the history of Puerto Rico, told through the lens of six hurricanes that have rocked the island over the last century. The book investigates the colonizing power of the United States and its effect on Puerto Ricans both on the island and in the diaspora, including the author’s own family. Mixing Spanish and English with attention to the poetic and psychological dimensions of language, Acevedo-Quiñones considers how traumatic events can reverberate through generations—on the grand scale of culture and on the smaller scale of intimate relations among parents, children, and extended kin. Jaquira Díaz, author of the memoir Ordinary Girls (Algonquin Books, 2019), calls The Hurricane Book “a multilayered, powerful book...a gift.” The author of the chapbook Bedroom Pop (Dancing Girl Press, 2021), Claudia Acevedo-Quiñones holds an MFA in creative writing and literature from Stony Brook University, where she taught poetry to undergraduate students. Her poems and fiction have appeared in the Brooklyn Rail, Radar Poetry, Wildness, and other publications. Originally from Puerto Rico, she lives in Brooklyn.

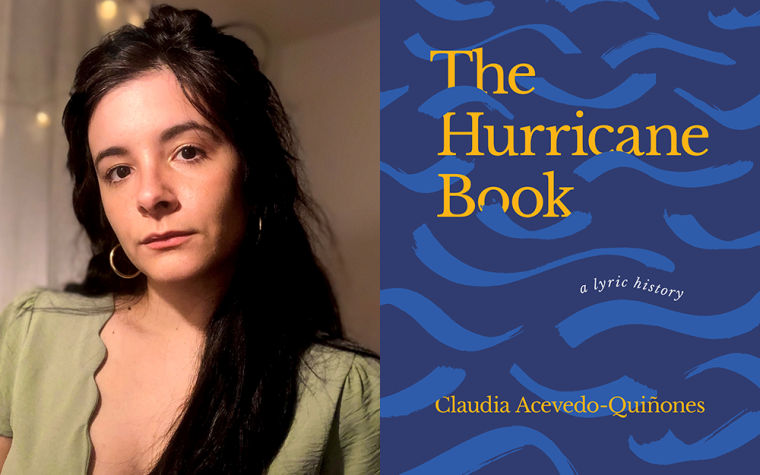

Claudia Acevedo-Quiñones, author of The Hurricane Book: A Lyric History.

1. How long did it take you to write The Hurricane Book?

I started thinking about it a decade ago, but most of the writing was completed over three years. When I sent the first draft to Rose Metal Press in 2020, I had been working on it for a year. The press decided to publish it on the condition that I expand and edit it significantly, so I did that between 2021 and 2023. Glad I did.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

It’s difficult to choose one thing! Most of it was challenging. I felt out of my depth in every way. I share an apartment with three roommates, so dealing with this subject matter for years in a little bedroom did a number on my mental health. I’m very mistrustful of my own memories. And I was writing about a country I left half a lifetime ago. There was this struggle between my need to show everything and my fear of it. I wasn’t working in my preferred genre. I was writing this hybrid lyric thing that was hard to fall into a rhythm with at first. But form is content and all that! I’m envious of writers for whom writing comes easily. It’s one of the most difficult things in the world for me. I can confidently say that the easiest thing about writing the book was working with the sections that dealt with irrefutable historical facts, however disturbing. It was truth I could count on when I doubted myself in other threads.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I often work multiple jobs and move apartments every couple of years, so the former impacts how, when, and where I write. If I could write in a sensory-deprivation chamber or in a tiny house by a creek every day between 7:00 AM and 10:00 AM, I would. I’m hypersensitive to all kinds of stimuli and lose my nerve exponentially as the day progresses, so I’m partial to writing as soon as I wake up—in bed on a legal pad—before most people I know wake up. There are periods in which I do this daily, and those are the times I feel most sane.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just read Yvette Siegert’s translation of Alejandra Pizarnik’s Diana’s Tree, and I am starting to read Brutalities: A Love Story by Margo Steines. I’m attracted to stories about exile, from our bodies or known places. I’m interested in seeing how some abandonments return us to ourselves and how others boomerang. One of the things I’m looking forward to the most after my book is released is reading with impunity! I haven’t had much time to do so with the book and a full-time job.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

I wasn’t actively thinking about their influence on my writing as I worked on the book, but I reached for Puerto Rican authors I grew up reading (Julia de Burgos, Luis Palés Matos, Mayra Santos, René Marqués, Rafael Acevedo) and wove them into the text because they were such an important part of my education. Authors who’ve impacted me significantly as a writer are Alejandra Pizarnik, Melissa Febos, Mary Karr, Lydia Davis, Claire-Louise Bennett, Elizabeth Bishop, Carmen Maria Machado, Ruth Stone, Adrienne Rich, and Louise Glück. This list is all over the place! But they’re always in my head.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of The Hurricane Book?

I didn’t show my family the manuscript before it was released, but there are a couple of close family members I reached out to about some sad, revealing content (in general terms). I didn’t want them to be too surprised if they read it. Their response was unexpectedly gracious, considering the subject matter. They basically said, “It’s your truth!” I’d been agonizing about it. But I now think people who know me understand that this was made with care.

7. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Only if the MFA program offers financial aid, health insurance, and/or a flexible schedule. I got a full ride and still had to work two jobs. I don’t know how single parents or caregivers do it. Yes, I learned a lot from authors I love and respect, but my MFA experience was good because of my peers. We were active in each other’s lives and gave each other consistent and constructive feedback. We had a magical bubble out in Southampton, New York, for those two years, and I’ll always be grateful for it. Those people are still my best friends. But writers don’t need to enroll in an MFA to find that community and structure. If you have/can get the money, go for it. But if you don’t, find a writing group, go to free readings and talk to the person you’re standing next to. If there are no writing groups where you live, start one. If there are no reading series, go to your local bar or coffee shop and ask if you can plan one. Put up flyers. Because there are writers looking for you, too.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you wrote The Hurricane Book, what would you say?

I’d tell her to worry less about the “why” of it. There’s a reason why you didn’t let it go, even if it’s still not clear. Get it done; do your best. Stop punishing yourself for not coming to any grand conclusions.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

There was a ton of research involved: I looked through ancestry and census documents to try to fill in the gaps in the family sections; sourced clips, photos, satellite images, and weather maps from newspaper archives, the Library of Congress, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Weather Service, and other government agencies; went through medical and academic articles for the sections on eugenics and post-hurricane response/relief. Thankfully I received a grant that helped me pay a fact-checker. I also had to have deeply uncomfortable conversations with my mother about our shared mental-health history.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

Marry rich! (I didn’t take that advice.) The second-best piece of advice was to start something new when I’m in a rut. We have to have a little fun, too, if we want to stay in love with what we do. After The Hurricane Book is out, you best believe I’ll be working on some sci-fi erotica for a bit.