This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Dana Levin, whose fifth poetry collection, Now Do You Know Where You Are, is out today from Copper Canyon Press. Working in a variety of forms, Levin explores the disorientations of personal and political trauma through individual and collective transformation. She writes: “So many bodies a soul has to press through: personal, familial, regional, national, global, planetary, cosmic— // ‘Now do you know where you are?’” Investigating a broad emotional, political, and literary landscape, from climate devastation to the global pandemic, Trump’s tweets to Google’s memory, Levin calls on beloveds and ancestors, great thinkers and religions to piece together a map of existence. “Through the fog of doubt, Levin summons ferocious intellect and musters hard-won clairvoyance,” a critic for Publishers Weekly writes in a starred review. “This terrific book will ground readers in the art of questioning, even as the ground quakes.” Dana Levin is the author of four previous collections of poetry, most recently Banana Palace (2016). Her first book, In the Surgical Theatre, was chosen by Louise Glück for the 1999 APR/Honickman First Book Prize and went on to receive numerous honors, including the 2003 PEN/Osterweil Award. Copper Canyon Press published her second book, Wedding Day, in 2005, and her third, Sky Burial, in 2011. Levin’s fellowships and awards include those from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Witter Bynner Foundation, and the Library of Congress, as well as the Rona Jaffe, Whiting, and Guggenheim Foundations. Levin currently serves as Distinguished Writer-in-Residence at Maryville University in Saint Louis, where she lives.

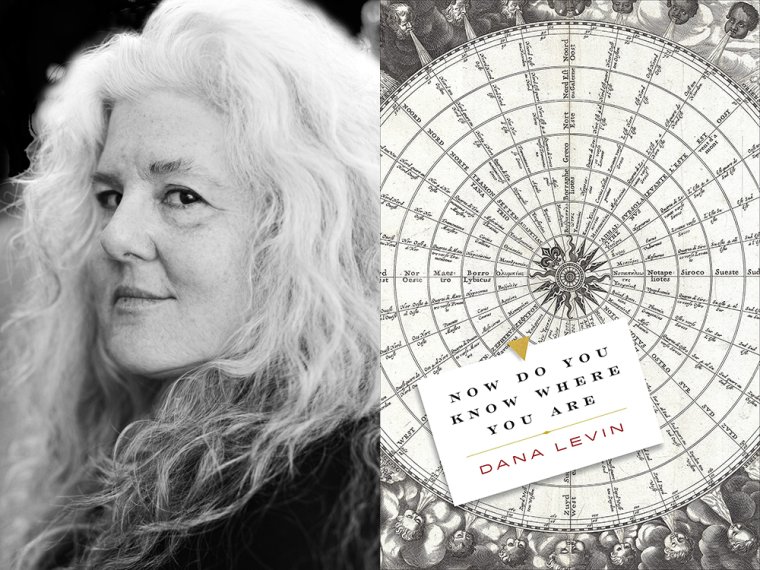

Dana Levin, author of Now Do You Know Where You Are (Credit: B. A. Van Sise)

1. How long did it take you to write Now Do You Know Where You Are?

Six years, with the most intense phase being 2017 to 2020.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Oh, what wasn’t a challenge. Our collective conditions 2016-2020, my midlife crisis of creative confidence, leaving Santa Fe after nineteen years for the unknowns of Saint Louis—the whole book is this question.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I am a fitful writer: long periods of not writing followed by intense engagement. As a young writer I could only work in the early morning, but now it’s late afternoon and early evening. I write at home: I pace around, I sit on the floor of my living room, I move to the computer, I pace around, I sit on the floor, etc. I also do a lot of musing on my back porch.

4. What are you reading right now?

Paul Tran, All the Flowers Kneeling—one of the strongest debuts I’ve read in a while: The subject matter is intense and the formal chops are inventive and sharp. I also just finished reading Vapor by Sara Eliza Johnson, out this fall from Milkweed: wow. This quote! “My infidel, before the wind tears our flesh: one more photon for your tongue.”

5. Which poet, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Ted Mathys. Read his books Null Set and Gold Cure from Coffee House Press. Brainy, brilliant, grounded in the real in eccentric ways, always deep and surprising.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Distraction, impatience, and lack of discipline.

7. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

Pacing around my sublet in Saint Louis, Fall 2015, saying out loud the words “No,” “Yes,” and “Stop” over and over: to feel how they felt in my mouth, my throat, my chest.

8. How did you know when the book was finished?

When I removed all the pandemic poems written during that first lockdown. I’d submitted the final manuscript to Copper Canyon in April 2021, but hadn’t felt completely right with it. Then one day, in late May, sitting out on the back porch, I had a late-breaking Aha!—to let the pandemic be a kind of foreshadowed presence, rather than actuality. Many poems were already suggesting this: Pandemic showed up in poems written before 2020, as an idea, and in a 2017 conversation recounted in the poem “Appointment.” Once I removed the lockdown poems, the book just clicked into a shape that felt right. Then in Fall 2021, I put one pandemic poem back in: “Into the Next Eden.” This poem answered a call: I’d written a poem called “No,” and one called “Maybe,” and kept attempting a “Yes” poem that could never get going. Then I realized “Into the Next Eden” was the “Yes” poem! I love how all three titles—“No,” “Maybe,” “Into the “Next Eden”—answer the question, Now Do You Know Where You Are?

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I have many initial readers, some who look at just one poem, some who engage whole manuscripts. For this book, the poet Gary Jackson was instrumental to my attempts at writing about race; Victoria Chang, to keeping the poems grounded in the strangeness of the ordinary. My sister, Caryn McCloskey, as well as Gaby Calvocoressi and Erin Belieu, offered encouragement to keep going (so crucial). G. C. Waldrep and Louise Glück are and have been primary readers for years: They are direct, they believe in my art, and they always tell me the truth, even when it stings.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

A paraphrase from Jack Kerouac: Don’t stop to think of the words, stop to see the scene better.