This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Devika Rege, whose debut novel, Quarterlife, is out today from Liveright. Rege’s novel is set in a time of rising Hindu nationalism and examines the forces that shape a society’s political beliefs through the story of a Wall Street consultant, Naren Agashe, who returns to Mumbai with a college acquaintance, Amanda, who plans to teach in a Muslim-majority slum and becomes involved with Naren’s brother, a charming filmmaker named Rohit. The novel was published in India in 2023, where it was nominated for five literary awards, eventually winning the Mathrubhumi Book of the Year and the Ramnath Goenka Sahitya Samman for Best Fiction. It was also named a best book of the year by over a dozen presses including The Hindu. The Indian Express called Quarterlife a “landmark novel” adding that “Rege has a vast descriptive repertoire, is willing to take astonishing risks with structure, and is immaculate in her numerous interiority dives.” Rege was born in Pune, India, and lives in Bangalore. She holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and has been awarded fellowships from Yaddo and MacDowell.

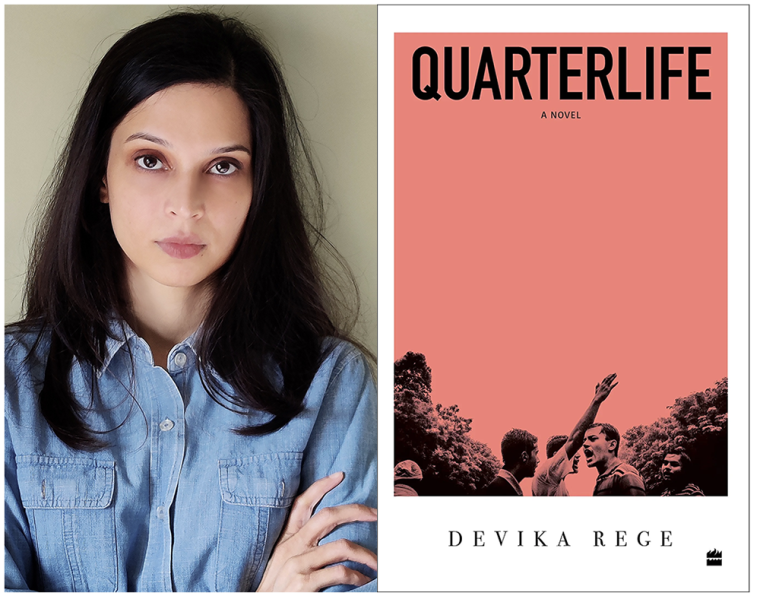

Devika Rege, author of Quarterlife. (Credit: Property of Liveright Publishing)

1. How long did it take you to write Quarterlife?

Almost a decade, though the bulk of the novel came together over an intense period of five to six years. I had returned to India after a degree abroad when Narendra Modi first came to power. Hindu nationalism became mainstream in a way that it wasn’t, and it divided my friends and family. I could see parallels in other democracies as well: Right-wing politics and conservative values were gaining hold, our political identities became all-encompassing, and dialogue was breaking down. I was anxious to make sense of how we got here, but the moment was evolving in unpredictable ways, and it took me a long time to grasp which aspects of it were transient and which had a longer or wider resonance.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The tension between empathy and judgment. In a time of rapid social and cultural change, relying entirely on my imagination to write even fiction felt like hubris. I spent years shadowing people across the political spectrum, including young men from right-wing party cadres. When we spoke, there were times I could feel my muscles going stiff. I had to discipline myself to shut up and keep observing because that is what writing fiction demands. Yet the task would be so much simpler if it ended with observation. You are creating a world and the world through it: There is a sense of responsibility. I was haunted by the question of how I could hold space for plurality and ambiguity without descending into moral relativism.

3. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Quarterlife?

After I graduated from college, I worked in a corporate sales job for four years. The job entailed traveling to fifteen states to meet all manner of clients. It gave me a sense of the country beyond the corner that I’d grown up in. It exposed me to a variety of people, their workplaces and homes, their fears and motivations. I’d say this was as important an education for a young writer as anything I did in the years after.

4. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I try to write on most mornings as soon as I wake up, but to say that’s how the novel got written would not be accurate. The most significant breakthroughs came when I was away from the desk and attending to other matters. Many of the scenes were drafted outdoors—standing in a protest or a religious parade or getting home on a curfewed night.

5. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Quarterlife?

How capacious the novel form is, how open. I don’t know if there is any other art form that offers a canvas as expansive and layered with meanings.

6. What are you reading right now?

I recently finished John Berger’s A Fortunate Man. I am nearing the end of J. M. Coetzee’s Foe. Namdeo Dhasal’s A Current of Blood is a favourite that I just reread because I want to give my editor in the U.S. a copy. It’s a searing work by one of Maharashtra’s preeminent Dalit poets that I believe should be published internationally.

7. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Another book I’m always gifting people is Shrikant Verma’s Magadh, translated by Rahul Soni. It’s a twentieth-century Hindi classic, a book of poems in which India’s ancient capitals become allegories for all great cities, political visions, and doomed utopias. It’s a devastating lament on power and time, but it’s also playful, a little like Calvino, with a darker and more ironical edge.

8. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

If a writer has never lived in a literary capital and the degree is free, it can be a great way to get exposed to the artistic conventions of the day. There is also some value in the short story workshop, but if a young novelist is serious about their education, they will have to go so much further. I’m thinking of exercises in historical and ethnographic research, visits to art museums, courses in philosophy and psychology. Craft is only one aspect of the work. There is no point in learning how to sculpt if you don’t know where to get the clay.

9. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Quarterlife, what would you say?

I would say that if you’re going to do this with a spirit of honest exploration, there will be times when you find yourself completely in the dark—when no one can tell you how to write the book you have set out to write or how to salvage all the missteps you have taken with your life to make this work possible. Try to remember in those moments that this is a good sign. That this is not a symptom of creative failure, but the essence of creative freedom.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

It’s a verse from a Rilke poem that is also a prayer. Let everything happen to you, beauty and terror. / Just keep going. No feeling is final.