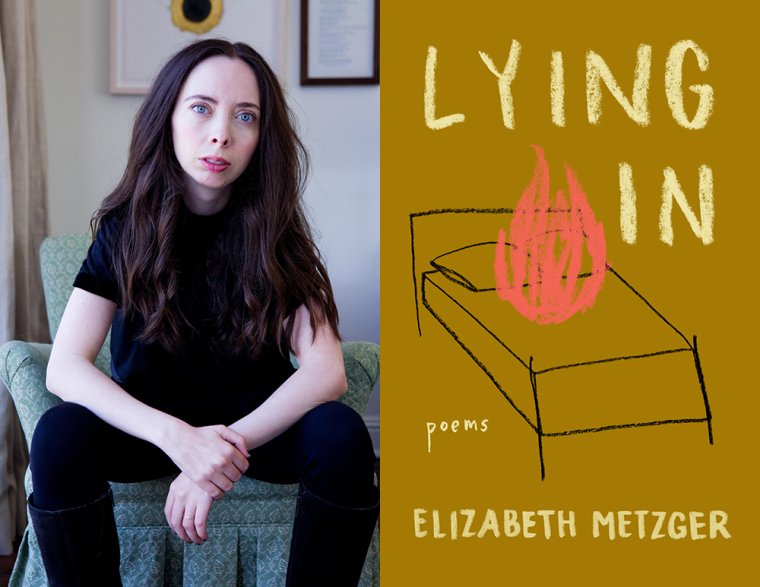

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Elizabeth Metzger, whose new poetry collection, Lying In, is out today from Milkweed Editions. These introspective lyrics consider the physical and psychic demands of motherhood and other forms of human relationship. Opening with a meditation on a difficult pregnancy—including a period of forced bed rest—the collection pushes back on the idea that gestation and birth are purely joyful experiences, exploring ambivalent feelings: “I curse my husband, // sometimes rant against the baby. // I hate most the sound of my own / demanding,” Metzger concedes in the title poem. “Can’t you just be gracious? Maybe every woman / has a voice that says this often.” Other poems contemplate how childrearing alters the nature of romantic love between parents, the way children can prompt us to see the world afresh, and the losses that inevitably occur alongside the emergence of new life. Kaveh Akbar calls Lying In “a book orbiting sacrifice, orbiting the way(s) one generation gives life then gives way to the next.... Elizabeth Metzger has become one of my favorite living poets.” Elizabeth Metzger is the author of The Spirit Papers (University of Massachusetts Press, 2017), winner of the Juniper Prize for Poetry. Her poems have appeared in the New Yorker, the Paris Review, Poetry, and elsewhere. She writes, teaches, and edits in Los Angeles, where she is a poetry editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Elizabeth Metzger, author of Lying In. (Credit: Yvette Roman)

1. How long did it take you to write Lying In?

About five years. The first poems in Lying In were written in the spring of 2016. The last poems, the two longer poems, and many about desire were written during the pandemic after my daughter was born, so 2020–2021. I ended up leaving the manuscript for a while and then revising it rather aggressively one last time in 2022.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The most obvious challenge was bed rest itself: I was often either too sick or too afraid to recognize or accept the risk of beginning a poem. While my first pregnancy involved a placental abruption and my second involved hyperemesis gravidarum, in both cases I felt my body as an obstacle to creativity. Another challenge, of course, was meeting the needs of an infant. When my second child was born, this was even more challenging, as there was also a toddler demanding me.

Entering the realm of the self, let alone a poem, seemed impossible. I had to fake it at first, go through my own former motions, even mourn and pine for some old self before finally a new voice woke me up from a rare postpartum sleep—it became the poem “Won Exit”—like a jealous sibling and said, Do you still want me? Once I said yes, it turned out the voice was mine.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I used to think I could only write in a silent room, alone, after the whole world was asleep. Fortunately my drive to write made my lack of time to write frustrating enough that I can now write in a car or while pushing a swing. The feeling of being hidden away remains the same and, wherever I write, I hope I am invisible.

I’ll have a couple months of silence during which maybe I force a few words here and there, but nothing takes root, and I discard all of it. Then I’ll have two weeks of writing every day, and it feels alive. I think of those intense bursts as the payoff for the silence—and, often, torture—that surrounds them. The writing phase feels simultaneously passive and like an extreme sport. As long as I pay attention: I hear a line, sometimes a wordless cadence, and that music keeps me company. Often this comes along with a level of feeling that is unsettling, obsessive, exhausting, if not unbearable. I’ll notice an object I’ve encountered every day of my adult life, and suddenly it brings me to tears, or better yet, clarity. Those are the moments I feel most human. I am not religious, but I do obey the writing rhythm superstitiously, if not spiritually. Language has a soul when you need it to.

4. What are you reading right now?

Most recently, I was blown away by From From by Monica Youn, Meltwater by Claire Wahmanholm, and Chariot by Timothy Donnelly, which I had the pleasure of hearing in its entirety. In prose, I’m revisiting Anaïs Nin, Audre Lorde, and Marguerite Duras, and thinking about how the erotic speaks to our fear of forgetting and being forgotten.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

My isolation in bed felt so determined by biological time that I had thought, for the first and maybe last time in my life, that my book would have a natural narrative arc: pregnancy. It did not turn out that way! Much of the book takes on a point of view, a distance from the world, that somehow also intensified my absorption of experiences long before and after bed rest.

I guess the ultimate organizational strategy turned out to be cutting poems. By removing about ten poems at the eleventh hour, there was enough space to intuit an architecture. I wrote the long title poem toward the end of the writing process, and while at first it began as a totally separate project, I soon realized it was the most narrative poem and would be grounding to place up front, a sort of trust-me move.

Another important organizational choice was ending the book on the poem “Desire,” which concludes with a question. I never want my last words to feel too final: It may be doubt itself that makes me write another poem, so I like to think that doubt was a kind of momentum for arranging as well.

6. How did you arrive at the title Lying In for this collection?

Before I knew my pregnancy was high risk, I learned that the term “lying in” refers to the first forty days after giving birth when one stays isolated from most others to bond with the infant and recover. I remember feeling grateful that there was an official term that would permit me to say no to guests at a time in my life when I felt both inhabited and very much a guest in my own body.

I was already in a cocoon of grief after my best friend’s death, and the idea of “lying in” spoke to my sense of inwardness as full of otherworldly communion. I think I have been drawn to such a concept, secretly, since childhood—but I had thought that only other species were allowed to hibernate. I hope the title captures the way isolation and intimacy had to become one and the same for me.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Lying In?

It surprised me that, on that page, making life came to be more about making more of life—my own. In Adrienne Rich’s incredible poem “Paula Becker to Clara Westhoff,” the pregnant speaker confesses: “Sometimes I feel / it is myself that kicks inside me.” This speaks to the surprise I felt finding that, in poems, I was my other creature, inside and outside myself. I was hardly offering language for my infant’s nonverbal experience, as I had imagined, but rather enacting my own revival.

In the course of writing the book, I lost two of my beloveds: the poets Max Ritvo and Lucie Brock-Broido. I felt the world shrink. What shocked me was that in their absence, they could remain catalysts for my own transformation. They offered themselves as audience for my thoughts and feelings, giving language a new, expansive purpose despite my ongoing sense of dumb devastation.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Lying In, what would you say?

I would say this to my past and present self: Some things you fear will happen, some things you fear will not, but everything you are afraid of will be surpassed by desires you cannot yet imagine.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I had to get comfortable with “wasting” time again: doing nothing, letting in the cries—not of my children, but of my own mind. One day early in the pandemic, in a desperate postpartum plea, I locked myself in my room for an hour and a half, while my husband wrestled our stir-crazy preschooler, and luckily the baby slept. When I emerged, my husband (supportive and exasperated) asked what I got done. The word “done” haunted me.

Whether I finished something or accomplished nothing, the fear that I would never find time alone again led me to spend the next six months of morning naps writing a 500-page autobiography, from childhood to the present, during which all that seemed to matter was never pausing. Once I was purged in prose, I ended up hearing poetry again and wrote many poems on my phone in a nursery glider, with the baby still latched to my body.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

Bring your full human, my great mentor Lucie Brock-Broido advised in one unforgettable workshop. At first, I was confused, maybe defensive. But she used the metaphor of an old anatomy book, which layers transparencies of our different physiological systems—digestive, circulatory, endocrine. Rather than ask for more information or explanation, she helped me intuit what I had been withholding.

I had previously thought of a poem as baring the soul, some purification, but her words made me reconsider. I now think the soul includes everything about a person, so everything about a person has a place in a poem: humor, rage, awkwardness, jealousy, even speechlessness. Lucie often delivered her wisdom in metaphor. Uncovering what she meant made the advice feel more like poetry than a rule. One need not be autobiographically accurate, of course, but to me there is no more satisfying and liberating way to understand clarity than as a kind of layering of self. Someone wants more of you.