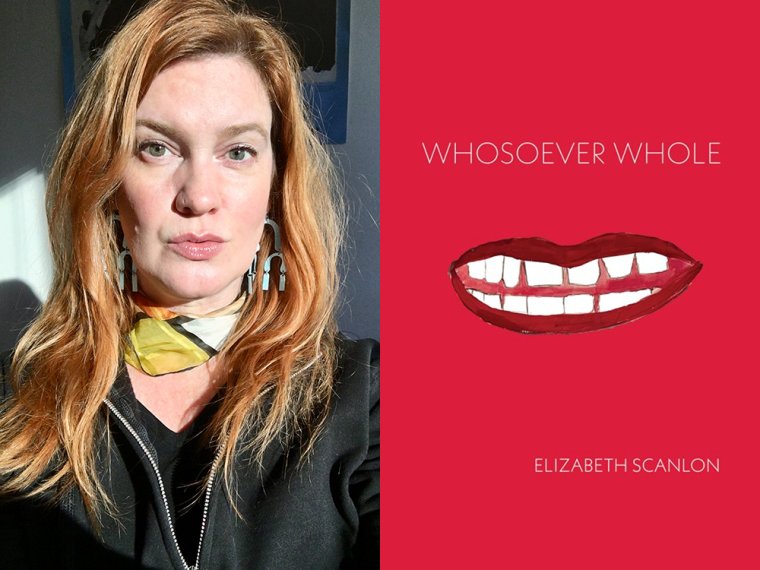

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Elizabeth Scanlon, whose new poetry collection, Whosoever Whole, is out this week from Omnidawn. In these intimate and often wry lyrics, Scanlon contemplates the absurdities and wonders of being a person and a parent in a vortex of capitalist consumption and climate crisis. Playing mini golf on a seventy-degree December day in Philadelphia, masochistically combing the internet for “something to hurt you,” or losing oneself in the zombie-apocalypse-industrial-complex: These are the disturbing new normal. Yet the poems see beyond the moment, linking contemporary emergencies and cultural shifts to those that have come before—for better or worse: “Those who lived right before the car had no idea / how utterly everything was about to change,” she muses in “Mood.” The timeless theme of parental love wends its way through the collection while upending clichés about the purity of motherhood and maternal sacrifice. In “Devotion,” for example, Scanlon declares, “Your mother is a creep. / Everyone’s mother is a creep; / we have envelopes of your teeth / in our bedside drawers, / clippings of your hair.” Publishers Weekly praises Whosoever Whole: “Scanlon’s excellent collection is determined to see to the heart of living and invites readers to do the same.” Elizabeth Scanlon is the author of Lonesome Gnosis (Horsethief Books, 2014) and is the editor in chief of the American Poetry Review. Her poems have appeared in Poetry Ireland, Poetry London, and elsewhere.

Elizabeth Scanlon, author of Whosoever Whole.

1. How long did it take you to write Whosoever Whole?

It’s never a straight line for me, assembling a book. I always have a file of poems that are marinating for years before I feel they are done, and then once they feel ready I begin the process of seeing how the pieces of the puzzle fit together. Some of the poems in this collection began ten years ago! But if we’re counting time from when I began to think of it as a book to when it was taken by Omnidawn, I’d say it was about four years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The vulnerability of writing about parenting. Even though poetry grants us the freedom of exploring a subject without being explicitly about something—I often find that what the poet thinks a poem is about and what the reader thinks are two completely different things—I’m still reticent to refer to my kid in my writing. Because, of course, our life together is not just mine; it is his as well. But I think I’ve threaded that needle.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

If jotting lines down in the Notes app on my phone counts, I write every day—and I think it must count, because it has become an irreplaceable part of how I see patterns emerge. I also keep a notebook with me because I like writing by hand when I can; I really enjoy ink and pencils and erasers, but that’s not always practical. I wish I were a person like Ursula Le Guin, who had an actual writing schedule that was not to be disturbed. Maybe I will get to be like that later in life, but thus far I am always fitting writing in wherever I can.

4. What are you reading right now?

So many things. I’m a stacker—I have a desk stack, a bedside stack, and a living room stack, and I rotate among them. I suppose it goes without saying that I’m reading poetry all the time, so I’ll focus on my non-poetry stack here. Books that I have loved most recently include: Miranda July’s All Fours; Elisa Gabbert’s excellent new essay collection, Any Person Is the Only Self; Lauren Groff’s The Vaster Wilds; another amazing novel by Anne Enright, The Wren, the Wren. Of course I read and loved Kaveh Akbar’s Martyr! Oh, and the new biography by Cynthia Carr, Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar. I’m about to read Michael Nott’s new biography, Thom Gunn: A Cool Queer Life. Can’t wait.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

It may not be immediately observable, but I grouped the poems into some broad themes—consumerism, family, identity—and then found that too pat, so I began to braid them differently, based more on mood. As in, Is this one inquisitive? Or declarative? I also benefited tremendously from the suggestions of Rusty Morrison and the editorial team at Omnidawn. It’s wonderful when someone can show you a different order that makes sense, even if it’s just a little adjustment.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I would, even though I myself did not. At the moment in my life when I might have gone to an MFA program, I was offered a job at the American Poetry Review (after having been an unpaid intern for two years while doing other paid work). I opted for the job. I like to think that the total immersion in poetry that the magazine has provided has been an education unto itself, but I also imagine that the time dedicated to focusing on your own writing that a degree program provides is unlike any other experience you may have.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Whosoever Whole?

I was a little surprised to see how much anger is simmering in these poems, when taken as a whole collection—the anger that I believe arises when you push back against the dominant American values, like prioritizing productivity or earning your keep. I found it interesting to embrace that, because anger can be clarifying.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Whosoever Whole, what would you say?

I think these poems are what I would say to the earlier me! We write what we need to hear sometimes. But to say it more concisely: You’re not failing. There is no score.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

All the mothering. And I suppose the psychological work of feeling okay about addressing issues of class and money, which are so bound up in shame.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

Keep your drafts! Or at least keep them long enough to see how your perspective changes. I have found writing to be like channeling; sometimes we receive messages that we don’t understand until we document them and return to them later in a different state of consciousness. Images align, sense forms. We may think we’re the painter, but we’re the paint.