This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Eugene Lim, whose latest novel, Search History, is out today from Coffee House Press. To read Search History is to fall through a series of trap doors. In the prologue alone, two characters topple through a series of disparate reincarnations: They attend an opening at a gallery, then suddenly they are workers in a cellphone factory, then pieces of debris in the Atlantic Ocean. In the ensuing sections, the novel continues to fall down such unexpected rabbit holes, but at the heart of the story is a madcap search for a dog who is believed to be the reincarnation of a dead friend. Often simultaneously hilarious and devastating, Search History is an adventure story that offers profound insight into grief and grieving in the contemporary era. “Search History is a luminous, peerless work that establishes Lim as one of the best-suited authors to write about our distinct moment of environmental decay amidst technological advancement,” writes Meghana Kandlur. “A heartfelt delight from start to finish.” Eugene Lim is the author of the novels Fog & Car (Ellipsis Press, 2008), The Strangers (Black Square Editions, 2013), and Dear Cyborgs (FSG Originals, 2017). His writing has also appeared in the Baffler, the Brooklyn Rail, Dazed, Fence, Granta, and Little Star, among other publications. He is a high school librarian, runs Ellipsis Press, and lives in Queens, New York, with Joanna and Felix.

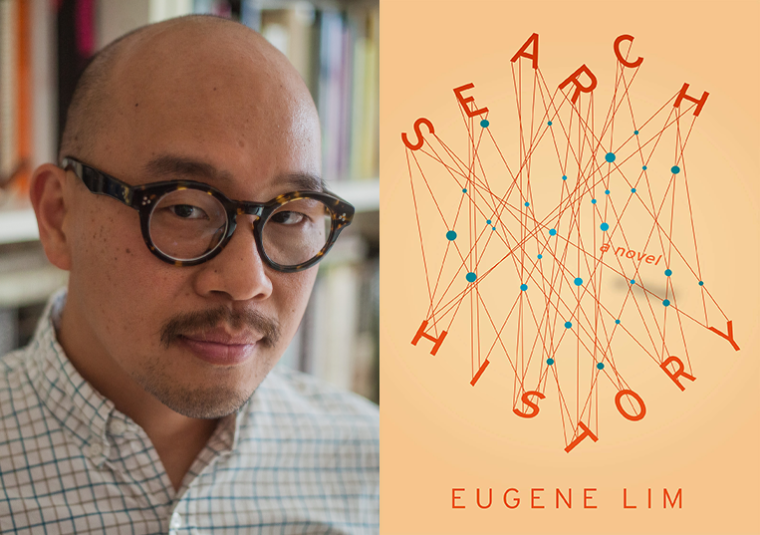

Eugene Lim, author of Search History. (Credit: Ning Li)

1. How long did it take you to write Search History?

About three years.

2. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

I remember thinking the title would be bad for SEO.

3. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Even if there are many things going on in it, I think at its heart this novel is a book about grief. And writing about that subject while enduring its wound makes you doubt yourself, makes you wonder whether one is being honest or honoring or insensitive or sentimentalizing. I wanted to articulate and be honest to the emotion of grief but also I wanted it to be both original and transformed by and into fiction—not so that the emotion was made into mere artifice but so that the artifice and strong emotions could stand together without either feeling manipulated or made false by the other. Also, trusting that the novel of disparate structures and methods was a novel, i.e. that it was more than a sum of parts.

4. Where, when, and how often do you write?

This is the struggle. All routines got upended since March 2020, but for this book, which I finished in roughly February 2020, I tried to write before or after work, as many hour-and-a-half sessions a week as I could manage, usually only two or three. Also, I work in a high school and am fortunate to have summers off, during which time I try to get in two or three such sessions a day. Prior to 2020 and I bet soon again, my preference is to write either in libraries, unpopular museum cafés, failing empty restaurants, or odd public spaces. In New York City, especially in midtown, there are odd “atriums”—public indoor plazas or food courts—which I believe developers include in their high rises in exchange for corporate subsidies and/or due to zoning requirements. Business folk crowd into them during the lunch hour, but the homeless, I, and other lonely citizens make use of these spaces in the quieter morning and evening hours. Some have the crucial advantage of public restrooms. I write by hand and during these times try and fail and fail and try to avoid the internet.

5. What are you reading right now?

I recently read and enjoyed Agustín Fernández Mallo’s The Things We’ve Seen, Percival Everett’s Telephone, and Mckenzie Wark’s Reverse Cowgirl. And I just finished a truly amazing book of matryoshka-like nested stories that somehow hold together, a 1946 crime novel called The Deadly Percheron by John Franklin Bardin. I’m also juggling some nonfiction and am in the middle of Ram Dass and Paul Gorman’s How Can I Help? and Mary Gabriel’s doorstop, Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Percival Everett is a comic wizard. He has great range, is truly weird, has the vision of a down-to-the-bone autodidact, seems beautifully stubborn. I’ve come to love a French writer named Jean Echenoz whose earlier noir-inflected novels are flat masterpieces. There’s a Korean American writer named Yongsoo Park who wrote an early surreal, somewhat provocative, and hilarious novel called Boy Genius, and who has self-published two beautiful memoirs called Rated-R Boy and The Art of Eating Bitter. The first is about growing up in Elmhurst, Queens, and the latter is about parenting.

7. What trait do you most value in your editor (or agent)?

Believing in you. Telling you what they think doesn’t work—in constructive detail—but understanding that it’s not their job to fix it. Being able to see the future. Getting one’s work to the right readers.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Search History, what would you say?

Keep stretching. Don’t be afraid to feel things deeply. And: It’ll all be okay.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

Definitely my wife, Joanna. She has great taste; she calls bullshit without hesitation; she reads very widely and voraciously. It’s an amazing thing to find a trusted reader. I have a handful, but Joanna is in all ways the greatest.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I’m not sure it’s the best, but in that Ninth Street Women history I mentioned, just today I read that Joan Mitchell’s high school art teacher gave them a set of rules, one of which—almost quaint in its romanticism—was “Art is not a career, it is one’s essence. And an artist, if serious, should expect to suffer and be poor.” This echoes a line of Merce Cunningham’s that every dancer probably has tattooed onto their heart, but which we should all heed when we choose this treacherous and magical path: “You have to love dancing to stick to it. It gives you nothing back, no manuscripts to store away, no paintings to show on walls and maybe hang in museums, no poems to be printed and sold, nothing but that single fleeting moment when you feel alive.” Merce is trying to contrast dancing to other art forms, but I think in that he was a little wrong. Not completely but a little. Essentially, art gives you nothing back but the moments of making. And thus too: You have to love writing to stick to it.