This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Frances Cha, whose debut novel, If I Had Your Face, is out today from Ballantine Books. If I Had Your Face is told from four points-of-view: Kyuri, Miho, Ara, and Wonna, four young women who all live in the same apartment building, each struggling to make their way in contemporary Seoul. Kyuri works at one of the city’s most expensive room salons where she entertains wealthy businessmen; Miho, Kyuri’s roommate, is an artist who has recently returned from school in New York City; Ara, who lives across the hall, works as a hair stylist; and Wonna, one floor below, is trying to have a baby with her husband. Shifting between her various narrators, Cha illustrates how each character contends with poverty, patriarchy, and increasingly impossible beauty standards. As the characters weather the heartache and stress of daily life, they find enduring strength in their friendships. “Each voice in this quartet cuts through the pages so cleanly and clearly that the overall effect is one of dangerously glittering harmony,” writes Helen Oyeyemi. Frances Cha is a former travel and culture editor for CNN International in Seoul and Hong Kong. Her writing has appeared in the Atlantic, V Magazine, and the Believer, among other outlets. A graduate of Dartmouth College and the Columbia University MFA program, Cha lives in Brooklyn, New York.

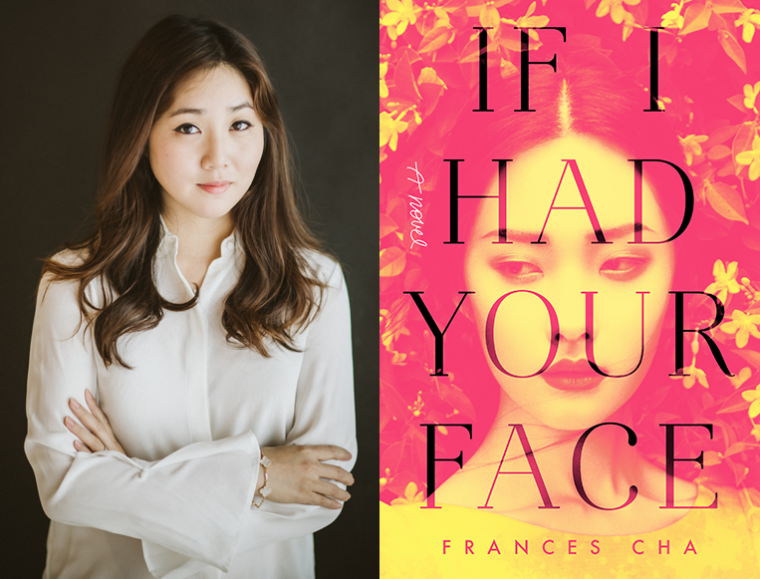

Frances Cha, author of If I Had Your Face. (Credit: Mia Jang)

1. How long did it take you to write If I Had Your Face?

From the first word on the page to publication day, it’s taken ten years. For the first half of that decade I was working full time and in the second half I had two children, so I was writing while being a stay-at-home mom.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Mustering up the bravado to continue writing for years in the dark when it felt like no one cared except for me. Since I was writing a novel set in contemporary Korea, and I had not seen another novel set in contemporary Korea come out from an American publishing house, I was also very afraid of the chances of making it past the gatekeepers. In the past, the few times I had brought up a book with Korean themes to people in the publishing industry, they had shaken their heads and said that the readership would be too small. The entire time before my book deal felt like I was writing with terrible heartburn.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

In Korea, where most of this book was written, my favorite place to write was at study cafés, which are usually used by high school students cramming for the college entrance exam. In every room there is a white noise machine, humidity is controlled, everyone gets their own carrel, and there’s free tea, coffee, juice, and a separate kitchen, and it costs $1.50 an hour. Pure, silent heaven.

In Brooklyn I write at home in the mornings when my kids are at school and then walk about thirty minutes to a writer’s workspace in the afternoons. It’s a fifth-floor walkup next to a highway and the desk I write at rattles when trucks go by, but it is my favorite place in New York. I need three things to write: snacks, drinks, and silence. I try to write every weekday.

When I used to live in Manhattan, I wrote in laundry rooms, hotel lobbies, apartment lobbies, and diners. All with sirens going off in the distance—we lived on the same street as a hospital—and music playing loudly above my head and bathrooms that I needed to ask for keys at the front desk. That was miserable in retrospect, but I was too desperate to know better.

4. What are you reading right now?

And the Dark Sacred Night by Julia Glass. A Winter Book by Tove Jansson. The Tenth Muse by Catherine Chung. A lot of magical children’s picture books too: The Book of Mistakes by Corinna Luyken, Cloud Bread by Baek Hee-na, and Being Edie Is Hard Today by Ben Brashares.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Tove Jansson’s Moomin books for children are astonishing to read even as an adult. Full of wistfulness, longing, whimsical characters, and truly imaginative plots. She is a brilliant writer.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

My urge to try to be a good mother. Oh, and this global pandemic.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Both my agent, Theresa Park, and my editor, Jennifer Hershey, are working moms of two and the most surprising and moving thing about working with them is how they always look out for me when it comes to balancing family needs with writing. They tell me to take care of myself first, which has been so comforting when I am constantly being hit with panic attacks for one reason or another—family emergencies, publishing in a pandemic, etcetera. And it is so encouraging to hear that they think I have a long career ahead of me, which in turns makes me consumed with the desire to not let them down.

8. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Cautiously yes, because it is a signal and a commitment to yourself that you have to do this or die.

9. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started If I Had Your Face, what would you say?

“You should really exercise more. Because writing requires perseverance and health. Read Murakami’s What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. Also, everything you’re writing right now is going to be edited or cut anyway, so stop poring over every word so painstakingly and being precious about it.”

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I used to reread Ann Patchett’s essay “The Getaway Car” whenever I got discouraged. There’s something wonderfully reassuring about her stories about waitressing at TGI Fridays while working on her first novel. It’s also packed with practical writing advice that I take to heart:

“Even if you’re writing a book that jumps around in time, has ten points of view, and is chest deep in flashbacks, do your best to write it in the order in which it will be read, because it will make the writing, and the later editing, incalculably easier.”

“Time applied equaled work completed.”

“Make it hard. Set your sights on something that you aren’t quite capable of doing, whether artistically, emotionally, or intellectually. You can also go for broke and take on all three.”