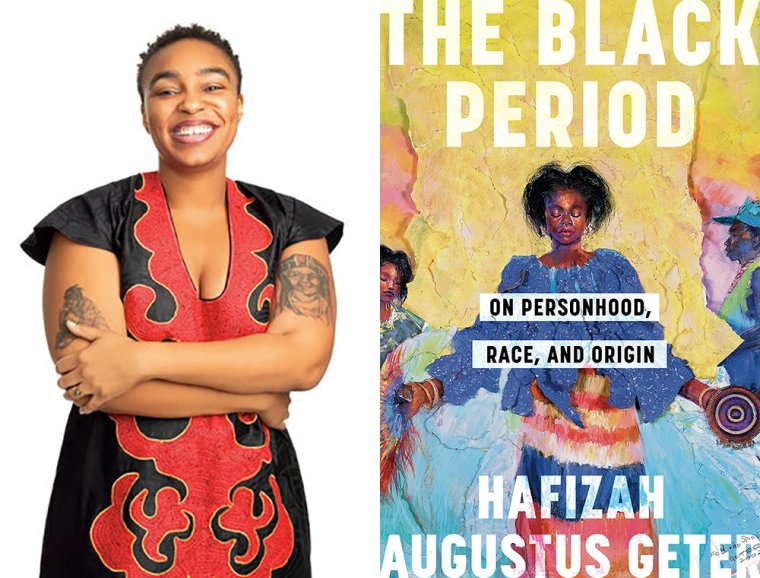

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Hafizah Augustus Geter, whose book The Black Period: On Personhood, Race, and Origin is out today from Random House. Part memoir, part searing political critique, the book charts a journey of self-discovery during a time of national and personal crisis. “I could see clearly that what history had unleashed on Black people was being used as a roadmap to harm others, and what was I supposed to do about that?” Geter writes. “And what did it mean to want love from a nation built on someone else’s erasure, on genocide, on stolen land?” These questions set Geter off on a quest to better understand her own mind and its formation within her family unit and the larger social structures she moves through, absorbing mythologies and ideologies that often undermine her identity as a queer Black immigrant living with disability. Geter moves back and forth in time, from her recent life—with wife Stephanie, chronic pain, and Black Lives Matter protests—to her upbringing by an American artist father and Muslim Nigerian mother to her coming of age amid the grief of her mother’s early death, a loss exacerbated by the Islamophobia of the post-9/11 period. Geter weaves in critical theory, U.S. history, and cultural analysis, narrating her own research process as she seeks to reeducate herself and build a new ethical framework in which lives like hers may thrive. Images of her father’s artwork—which cast a loving eye on Black life—appear throughout the chapters, offering a humanistic counterpoint to the cruelty Geter uncovers as she mines the nation’s archives. Kirkus praises The Black Period as “a resonant collage of memories, soulfulness, and elective, electrifying solidarity.” Hafizah Augustus Geter is the author of the poetry collection Un-American (Wesleyan University Press, 2020), an NAACP Image Award and PEN Open Book Award finalist. A literary agent, Geter has published writing in the Believer, Bomb, the New Yorker, the Paris Review, and many other outlets.

Hafizah Augustus Geter, author of The Black Period: On Personhood, Race, and Origin. (Credit: Beowulf Sheehan)

1. How long did it take you to write The Black Period?

I began thinking about the book in 2016. I wrote what would become chapter 5 in 2017 but began the book in earnest in 2019 and sold it to Random House in early 2021.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

It’s easy to lose yourself in writing and in dreaming of a finish line, but the stories we tell are never just about ourselves. It takes a lot of intentional work to write ethical stories. When you start to put in the work, you quickly recognize just how much “good intentions” are nowhere near enough. I learned a lot about the importance of humility. Despite the enormous amount of research I put in, I got things wrong. I’m very thankful to the writers, editors, and sensitivity readers who called me to account for every detail.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write in my home office, which is cozy and customized. I’ve painted the walls with dry erase paint, and it allows me to wear my brain on the outside when I’m writing. I don’t follow any particular writing schedule, but I tend to be pretty single-minded and obsessive when I’m in a project. I gather time wherever I can. I write on my phone, in cabs, on the train. I use a voice-reader app and listen to what I’m writing so I can edit on the go—when I’m cooking, running, going on walks.

4. What are you reading right now?

I tend to read several books at once. Right now, I’m reading: Severance by Ling Ma, Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy by Barbara Ehrenreich, No More Police: A Case for Abolition by Andrea Ritchie and Mariame Kaba, The Overstory by Richard Powers, The Next Great Migration: The Beauty and Terror of Life on the Move by Sonia Shah, and the poetry collections Hard Damage by Aria Aber and Dispatch by Cameron Awkward-Rich.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

The Black Period is about how the origin stories we inherit can be remade. That required an unmaking first. I went in search of the histories—mine and others’—that colonization has tried its best to erase. I wanted to understand all the ways that grief is a political condition through the complicated ways I had to grieve the death of my Muslim mother in a post-9/11 world. I wanted to explore the importance of collective anger alongside the question, Could I forgive my mean aunt? I wanted to understand the ways my shame around disability and queerness were a part of the political project of America. Could I write a new origin story? To figure all of this out, I spent a lot of time in the minds and work of abolitionists, writers, and critical thinkers, including Mariame Kaba, Angela Davis, Christina Sharpe, Mia Mingus, Harsha Walia, Aracelis Girmay, Naomi Shihab Nye, and Jill Stauffer.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of The Black Period?

The book went through some radical revisions every time I sat down to revise. I saw just how many books live inside the book yours is waiting to become. I learned to love revision deeply and in a new way.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

It wasn’t one thing in particular, but my agent Ayesha Pande is an incredible editor. Over the course of us editing the book and preparing it for submission, through each round of edits, she was a rigorous reader. Her notes pushed me to go further, to commit more fully. Without her edits, the book never would have found the amazing editor I have in Jamia Wilson.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Black Period, what would you say?

You will finish it.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I wanted to write a book that was as mimetic to the experience of living as possible. We don’t live life on a straight line. Time meanders, speeds up, and slows down. It doubles back—time remembers, and it forgets. The political sphere mixes with pop culture, race, desire, grief, education, sports, how we tell stories, and how we do or don’t come together. To write The Black Period I took in as much information as I could: I lived on JSTOR. I consumed hundreds of audiobooks and had hundreds of hours of conversations with other writers and critical thinkers. I paid attention to conversations on Twitter. I read newspapers, magazines, craft books, and book reviews. I listened to podcasts, including NPR’s Code Switch, Another Round with Tracy Clayton and Heben Nigatu, and Still Processing with Wesley Morris and J Wortham. I read histories of the Indigenous tribes I wrote about and reached out to organizations like the Native American Disability Law Center. The more histories I uncovered, the richer the writing became.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

My father is a visual artist. When he went to college to study art, the main thing my grandmother wanted to know was: Was his work going to help people? It was advice in the form of a question. My memoir contains almost seventy images of his artwork, and you can see the way my grandmother’s question lives in the work my father makes. I carry my grandmother’s question with me in my own writing.