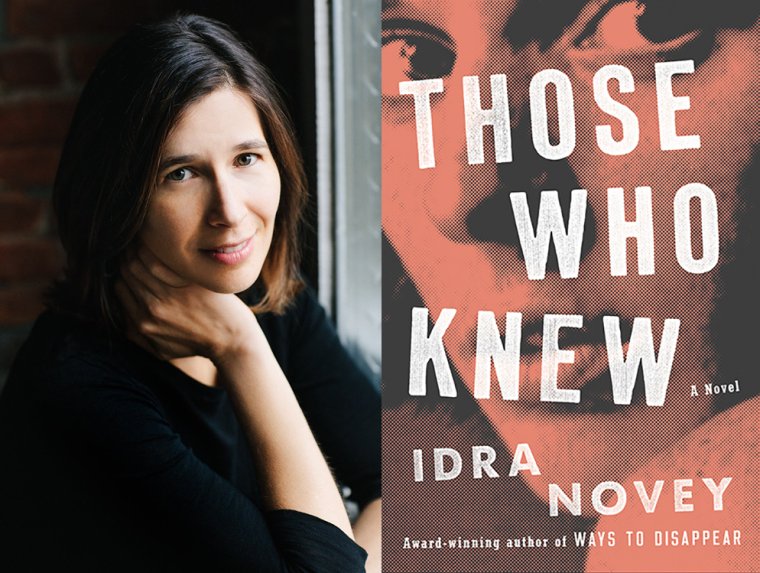

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Idra Novey, whose new novel, Those Who Knew, is out today from Viking. Set in an unnamed island country, Those Who Know is the story of Lena, a college professor who knows all too well the secrets of a powerful senator whose young press secretary suddenly dies under mysterious circumstances. It is a novel about the cost of staying silent and the mixed rewards of speaking up in a divided country—a dramatic parable of power and silence and an uncanny portrait of a political leader befitting our times. Novey is the author of a previous novel, Ways to Disappear (Little, Brown, 2016), winner of the Brooklyn Eagles Prize and a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for First Fiction, as well as two poetry collections: Exit, Civilian (University of Georgia Press, 2012) and The Next Country (Alice James Books, 2008). Her work has been translated into ten languages, and she has translated numerous authors from Spanish and Portuguese, most recently Clarice Lispector. She lives in Brooklyn, New York, with her family.

Idra Novey, author of Those Who Knew.

1. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I have the most clarity writing at home on the sofa in the early morning. Sometimes it is only one silent hour before everyone else in my apartment wakes up. On weekdays, if I’m not teaching and don’t have any other commitments, I try to get in another long stretch of writing after my children are off at school. Usually, I return to the same spot on the sofa and try to trick myself into focusing the way I did sitting in that same spot earlier in the morning.

2. How long did it take you to write Those Who Knew?

Four years. My earliest notes for the novel are from 2014 and I’ve written endless drafts of it since then.

3. What was the most surprising thing about the publication process?

I started this novel long before a man who bragged about groping women became president and the silencing of victims of sexual assault became an international conversation. It was startling to see the issues around power imbalances and assault I had been writing about every day suddenly all over the news, especially during the Kavanaugh hearing, when the patriarchal forces that protected Brett Kavanaugh mirrored so much of what occurs in Those Who Knew.

4. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

Translated authors are often relegated to a separate conversation in the United States. The number of translated authors reviewed and published in this country has steadily increased since I began translating fifteen years ago, but there remains an “America First” approach to how literature is discussed in this country, which is such a disservice to writing students and readers, especially now. To see how writers in other languages have written about deep divides in their countries can illuminate new ways to write and think about what is at stake in our country now.

5. What are you reading right now?

Rebecca Traister’s Good and Mad and alongside it The Tale of the Missing Man by Manzoor Ahtesham, translated by Ulrike Stark and Jason Grunebaum. I love juxtaposing reading at night from very different books and seeing what they might reveal about each other.

6. Who is the most underrated author, in your opinion?

Of the many I could name, Chilean writer Pedro Lemebel is among my favorites. He has an extraordinary novel available in English, The Tender Matador, translated by Katherine Silver. Every time I include The Tender Matador in a class, students end up clutching the book with both hands and commenting on how crazy it is that more readers don’t know about Lemebel.

7. What trait do you most value in an editor?

An openness to communication. I value so many of the strengths that my editor Laura Tisdel brought to Those Who Knew and also to my first novel, which she edited as well. But on a daily basis what I treasure most about our relationship is her willingness to talk through not only changes to the novel itself, but also the cover design, and all the decisions that come up while publishing a book.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Paralyzing doubt. I doubt every word of every sentence I put down. And when I manage to convince myself a sentence can stay for now, the next day when I reread it, I’m often overcome with doubt all over again about whether it’s necessary and whether what goes unsaid in the sentence has the right sort of tone and resonance.

9. What’s one thing you hope to accomplish that you haven’t yet?

To get through even half an hour of writing without feeling paralyzed with doubt would be a welcome experience in this lifetime.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

A teacher once scribbled on a piece of writing I handed in, you should be optimistic. Optimistic about what? The note didn’t say, but that vague advice has stayed with me because it’s true: To sit down and write requires a degree of optimism. You have to trust that there is relief to be found in placing one word after another.