This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Ismet Prcic, whose second novel, Unspeakable Home, is out today from Avid Reader Press. In this structurally ambitious piece of autofiction, readers follow along as Izzy Prcic, who is living in his car in Salem, Oregon, writes fan e-mails to commedian Bill Burr. The missives are interspersed with short stories written by Izzy and narrated by characters who represent different versions of himself. Idra Novey calls Unspeakable Home “a profound novel of extraordinary emotional honesty.” Ismet Prcic was born in Tuzla, Bosnia-Herzegovina, in 1977 and immigrated to America in 1996. His first novel, Shards (Grove Press, 2011), was a New York Times Notable Book, a Chicago Sun-Times Best Book of the Year, and the winner of the Sue Kaufman Prize and the Los Angeles Times Art Seidenbaum Award for first fiction.

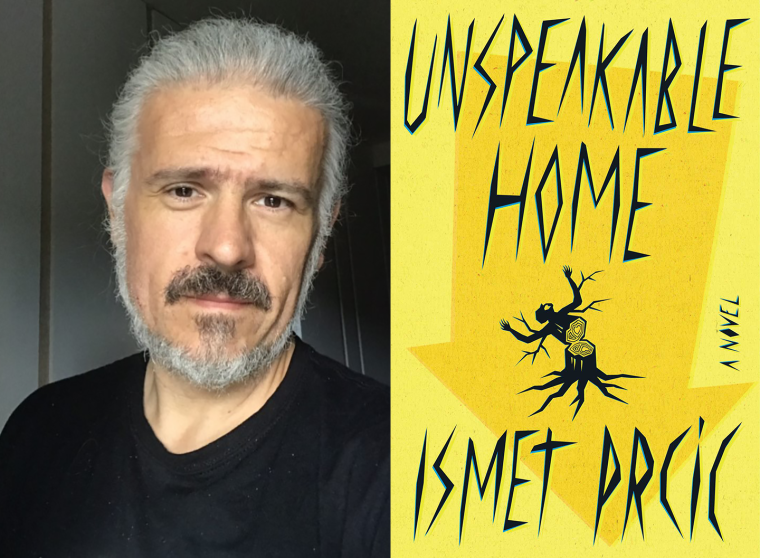

Ismet Prcic, author of Unspeakable Home.

1. How long did it take you to write Unspeakable Home?

I seem to have escalated into one of those writers who uses the art of writing as therapy, as a soul cleanse for the purpose of healing my traumas (to the chagrin-lite of a lot of my writer friends who are pure fictioneers, all lovely, powerful people in their own right whom I’m elated to read, by the way). And just like therapy, it takes time for it to work. My first novel, Shards, took me seven years to write, two to edit, and two more to bring into the world. Immediately after publication, everyone in my life wanted to know when the next one is coming. In about eleven years, I quipped. At the time I dreaded writing another novel and so conceptualized Unspeakable Home as a collection, to save myself some time, I thought. But it seems that words have the power of manifestations and that the second book is following in the exact time frame that I announced to myself back then. So, be careful what you say aloud; something inside you hears it and makes it so. Also, be careful of any perceived shortcuts. Books will tell you what they are and will not budge or open to you until you listen to what they have to tell you.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The hardest thing was letting go of the idea that Unspeakable Home is not a collection, that I don’t know how to write a collection, and that I should have known that I’ll always be a novelist. See, I’ve got something called diarrhea of the nag (shoutout to Mr. Show With Bob and David); I can’t help overwriting, complicating, adding in. Shards was close to nine hundred pages at first draft. I’ve eighty-sixed over two hundred out of the second one. Once I capitulated that it was a novel, things went pretty smoothly, though there was a lot of work to do still. I was in my element, perhaps.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I treat my life as fodder for literature, so I consider living it (surviving it) as part of writing. Dreaming is writing too. So is reading and playing and wasting time. But actual putting down of words, I’m best at the butt-crack of dawn; I wake, and before I can ever remember who I am, before the “shave, shit, shower and a shoeshine,” I drag myself to a writing space of the moment (no light but the one coming from the screen) and I type until I become aware of myself, or my surroundings. That’s how I get the subconscious on the page. Then it’s time finally for that morning routine, sometimes accomplished already by 7 A.M., other times by lunchtime. The rest of the time, it’s sternly sifting through all that madness and shaping it into something that could be of interest. But there’s always a notebook in my vicinity, to ensnare words and images, firm goads and loving whispers from the Universe.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’ve just reread The Fountains of Neptune by Rikki Ducornet, an ecstatic favorite of mine that inspires and humbles simultaneously. Currently reading Toni Morrison’s Paradise (love, love, love) and the beautifully haunting debut by Brendan Shay Basham called Swim Home to the Vanished.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf started it all at fifteen, especially the For Madmen Only part, printed in red in my mother’s copy; I was hooked for good. While waiting for my papers, illegally in Croatia, I read Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and knew that I had to become a writer. Sarah Kane, that British playwright extraordinaire, taught me how to listen to the text. Bukowski showed me how to hunt for ordinary graces and ecstasies. John Edgar Wideman is my American Bard; him and Rikki Ducornet reach levels of mysticism through their writing that are unmatched. When I grow up, I’d like to be like them. My spirit-writer is the good ol’ Samuel Beckett.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Unspeakable Home?

The biggest surprise came when, after my divorce and a couple of suicide attempts—surviving in a tiny flat that used to be a motel room in Salem, Oregon—I decided to try and heal, start anew again. Every twenty years I seem to do this, spending a decade writing about how the previous one messed me up. I reread what used to be my collection of short stories and with these new, forward-facing eyes, suddenly realized that there were a lot of, well, vaginas in them, (though I only saw three up close) and in the weirdest places to boot, always kind of in the background. See, some of the writing chunks that didn’t make it into Shards, I’ve repurposed into the new book and when I found the phrase hallucinate about pussy in one of these earliest of my attempts to write, it dawned on me that, throughout my whole writing life, there was something from my past that wanted to come out into the light, to bleed through, so that it can be seen and healed. Also, coming upon an academic paper about Shards right as I was figuring out how to end Unspeakable Home was a boon from the sky.

7. What is one thing your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

They were both, over the years, perfectly spot-on about what chunks of writing should not be in the novel. Thank goodness for their thinking brains and feeling hearts to so lovingly check my blind spots for me.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Unspeakable Home, what would you say?

I think that my answer to this one can be gleaned from the previous answers. :)

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book

Inner work, definitely, but coupled with somatic therapy, scouring the body for where the old traumas made their camps and integrating them. There was meditation and an exercise routine, to keep these new-found gains. I had to forgive myself for wrecking my life, find grace in all the terrible things I did or suffered, see them as necessary to go through for who I was becoming, and then try to find a way to alchemize them into art.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

Aleksandar Hemon answered a fan letter of mine early on in his career. I asked him, how does he do it, write these delightful, cohesive stories, after everything he’s been through. Everything I write, I complained, comes out in these chunks, these shards of narrative that don’t fit together. He replied, “You have a life story, and for that there’s no form that already exists. You have to find a form that fits your life story.” I was free then, off to the races.