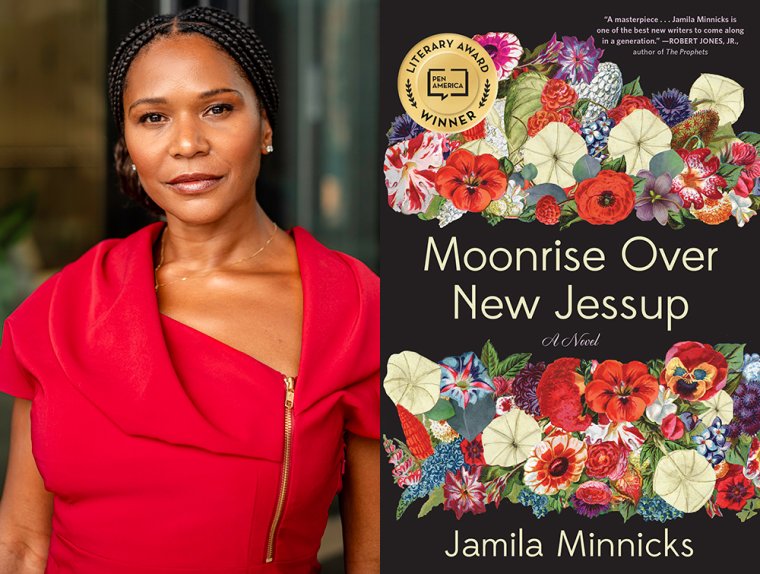

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Jamila Minnicks, whose debut novel, Moonrise Over New Jessup, is out today from Algonquin Books. This winner of the 2021 PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction, tells the story of Alice Young, who flees her Alabama hometown in 1957, hoping to eventually join her sister in Chicago. Down on her luck, Young finds herself instead in New Jessup, an all-Black Alabama town that has a strong sense of community and a commitment to self-reliance. While New Jessup feels at first like paradise, insulated from the racist violence Young had fled, the town is caught in the crosshairs of national politics and calls to desegregate. When Alice marries Raymond Campbell, a local activist pushing for change in New Jessup, she enters the fray of a historical push for racial integration in the aftermath of slavery and Jim Crow. Barbara Kingsolver, who established the Bellwether Prize in 2000, praises the novel: “With compelling characters and a heart-pounding plot, Jamila Minnicks pulled me into pages of history I’d never turned before.” Jamila Minnicks’s work has been published in CRAFT, the Write Launch, and the Silent World in Her Vase. A graduate of the University of Michigan, Howard University School of Law, and Georgetown University, Minnicks lives in Washington, D.C.

Jamila Minnicks, author of Moonrise Over New Jessup. (Credit: Samia Minnicks)

1.How long did it take you to write Moonrise Over New Jessup?

The first draft of Moonrise Over New Jessup took two months. I had completed my NaNoWriMo 2019 novel—which remains safely tucked inside a now-retired laptop—and then spent a month or so writing shorter fiction. In early June 2020, I had planned to return to the NaNoWriMo project, but a scene rooted in my imagination and demanded to be written: a family debating the merits of Brown v. Board of Education around a holiday dinner table. So I started writing Moonrise Over New Jessup as another short story, since my short fiction usually begins with an all-consuming idea.

The scene and dialogue came quickly, but before long the vision of Alice gliding around the periphery of the table—sliding the turkey onto the cloth, dishing collards onto plates—captured my attention for what she wasn’t saying. Instead, a wry, knowing smile gently twisted the corners of her lips as she listened and moved. The Alabama spice behind her smile is second nature to the women in my family, so Alice’s look assured me that she knew her own mind about the issue, and that the folks fussing at the table knew her mind about things too. That’s when I knew her story was the story, and the novel came quickly after that.

In early August 2020, I learned that the PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction was accepting manuscripts. New Jessup was a piece of my heart—I loved Alice and the people around her, and was proud to memorialize what life was like in some Black towns and settlements here in the United States. But I had not written New Jessup with publishing success in mind. I am a huge fan of Barbara Kingsolver’s work, and thought the prize presented a great opportunity to center Alice in a midcentury Alabama narrative while also highlighting the historical diversity of lives lived in real Black towns and settlements. So I revised the draft two more times and submitted an hour or so before the midnight deadline.

Barbara Kingsolver telephoned in February 2021 with news that I won the PEN/Bellwether Prize! I thought a friend was teasing me at first, but it was indeed Barbara Kingsolver. She endows this incredible award, which also guarantees a publishing contract with Algonquin Books. After completing final edits, I sent Moonrise Over New Jessup to the printer about five months ago.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

That I always had more creative energy than time when writing New Jessup. In 2020, I was working as an attorney. My early mornings were devoted to creative writing so that my first thoughts of the day were reflective and nourishing. Immersion in New Jessup provided an outlet for my creativity, fortified my spirit, and amplified my voice; particularly since legal writing is technical and rigid, and my work environment was disagreeable. The back and forth between my creative space and my legal job was hard, but the writing was my joy.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write daily, beginning at 4:00 AM. Of course, there are times when I’ve been under the weather or out too late to make that hour productive, but since I started Moonrise Over New Jessup, there have been only a handful of days that I’ve slept in. At that hour, my dream world and my waking world are one world. Sometimes I awake without a clear writing direction for the morning. When that happens, I write the thoughts and impressions coming to me from this liminal place—where language is malleable and it feels like I am in closer communion with my ancestors. Some of my best work has come from that practice, so even though I am no longer practicing law, 4:00 AM is still my favorite hour to get up and write.

4. What are you reading right now?

I usually read, and reread, several books at the same time, and recently finished a great selection that included Dionne Irving’s The Islands; Laura Warrell’s Sweet, Soft, Plenty Rhythm; Toni Morrison’s Mouth Full of Blood: Essays, Speeches, Meditations; Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl; Chantal James’s None but the Righteous; Cleyvis Natera’s Neruda on the Park; Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man; and Jason Mott’s The Returned. It will take me some time to build up another round of books, but so far I am into Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead, Clint Smith’s How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America, Carlo Rovelli’s The Order of Time, and Black Folk Could Fly: Selected Writings by Randall Kenan.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

This is a long list! From Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Deesha Philyaw, Robert Jones Jr., Gayl Jones, Ralph Ellison, Maurice Carlos Ruffin, Nate Marshall, Sonia Sanchez, Gwendolyn Brooks, Maya Angelou, Margaret Wilkerson Sexton, Imani Perry, Zora Neale Hurston, Chinua Achebe—the list feels like it could go on—I learned to write about my people with bravery, honesty, and care. Like Morrison, I hope everyone picks up my stories. But these authors prioritize, and immortalize, Black people and our history in their work. I am humbled and honored to be part of that tradition.

Barbara Kingsolver’s characters invite readers into the deepest regions of the human psyche, and Claire Messud’s work is a study of the smoldering page after page. Heidi W. Durrow’s thought-provoking work demands your attention and sparks important conversations, and Gabriel García Márquez’s breathless prose is in a class of its own. There are many others whom I love—because, at the end of the day, a large swath of inspiration only helps writers develop their own style.

6. What have you learned about the publishing industry that you wish you’d known before you published this book?

I knew very little about the industry before winning the PEN/Bellwether Prize. This was a blessing because I learned that separating the art of writing from ideas of publishing success best serves my creative purpose. I am infinitely grateful to Barbara Kingsolver and the PEN/Bellwether jury for appreciating and selecting New Jessup for the prize, and grateful for the extraordinarily caring way Algonquin has introduced the world to Alice and her folks. It has been an experience watching the publishing machinery at work—engaging with editorial, design, marketing, and publicity professionals—and I have a great deal of respect for all of the people involved in the process of making my book.

But ideas about major publishing success did not influence my writing in Moonrise Over New Jessup; nor is it a consideration for any of my other work. I realize now that established writers, agents, and editors routinely counsel emerging writers about the importance of separation between the art and their expectations in business. This sentiment is regularly repeated in trade publications and blogs that I read, and by industry veterans at writers’ conferences. But I had never heard this advice before writing New Jessup. My approach to historical fiction is to write from a place of honesty, creativity, compassion, and intelligence to avoid creating historical distortion, and I always believed that if I wrote with purpose and integrity, my work would find its true readers.

Before the PEN/Bellwether Prize, my most audacious goal for Moonrise Over New Jessup was to self-publish the novel and ride it around Alabama, distributing it to family from the trunk of my car. I am immensely grateful for all of the effort going into widening my audience. The opportunity to introduce the world to Alice, and her unique role in Black history, is a blessing separate and apart from the creative work.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Moonrise Over New Jessup?

The complete immersion into New Jessup during the writing and editing process. My mama’s people are Alabama for at least four generations. There are nods to inside jokes and anecdotes about ancestors passed down through the generations throughout the book. Writing about New Jessup, Alabama—the people, the conversations, the fellowship—provided a bridge to elders and ancestors who lifted me, carried me, and reminded me that I never walk alone.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you wrote Moonrise Over New Jessup, what would you say?

That there is more than one way in the world to have a voice. I chose law school with dreams of becoming a Supreme Court practitioner, fighting eloquently for civil rights with every brilliant keystroke and utterance before the storied tribunal. That never happened. Being an advocate for my community is part of my DNA, and I spent my career with an eye toward how the work I was involved in impacted Black people. I worked in a lot of spaces where I was the only Black person and tried to use my voice to raise perspectives that were not being considered. Maybe some people heard me, maybe not; but when communities you care about remain routinely underserved, despite your best efforts, you realize that your voice may be better suited elsewhere. So I sought elsewhere with my writing.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

There were a number of things I had to do to find, and maintain, my creative center and focus. My mama spoke with pride about growing up in Alabama—giving a much fuller picture of her life than I found in my high school textbooks, or in much of canonical literature—so that love for the soil has always been with me. I fellowshipped with family and longtime friends—sometimes to get a new take on Mama’s stories, to learn new stories, and always to be surrounded by love. My family strengthens me and keeps me grounded.

This book was also an opportunity to meet new “family”: my dear Montgomery “aunties,” some of the extraordinarily dedicated mayors and community leaders in the Historic Black Towns and Settlements Alliance, African American Studies scholars, and elders with a treasure trove of memories about places that inspired New Jessup. My research about Black towns and settlements has taken me to archives large and small, historic one-room schoolhouses, Black towns and settlements north and south—both living and in memory—front rooms and front porches, May Day celebrations and founders’ day festivities, and banquets and Sunday suppers. Research was integral to bringing New Jessup to life, and I also read a lot, listened to podcasts, and even watched YouTube videos for real-time glimpses of what life was like in these communities.

I need to live life to make art—to eat and dance and laugh and travel and feel things. Exercise is a must—I usually combine a long walk with a barre or yoga class or weight training. My coffee pot has a timer, so when set overnight, the aroma urges me from underneath the blankets in the morning. And music! I couldn’t have written this book without my playlist, and I can just about remember the songs that drove each scene in the book. Moonrise Over New Jessup is a story about our lives, and music has been a salve, a joy, a message, a haunt, a celebration in Black life since before we even landed on this soil.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

To write your story because no one else can write it. Writers approach the same person or event or era of historical significance through their own unique lens. When we lean into where our hearts guide us, the words on the page reflect our style. It is important to understand craft rules and to read widely, because we see how others follow, and break, those rules. But ultimately our work should reflect our own vision and our own voice.