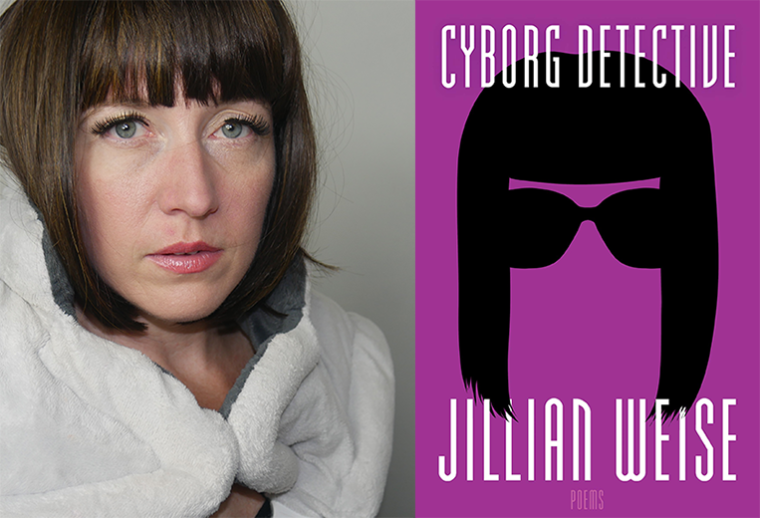

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Jillian Weise, whose poetry collection Cyborg Detective is out today by BOA Editions. The poems in Weise’s third collection investigate and challenge the ways in which nondisabled writers have appropriated disabled bodies. “Populated with a variety of voices that speak with a sort of sly candor that can only be prompted by the most intimate inquiries, this book is a true ventriloquist act,” writes Cate Marvin. “With a thrilling lack of remorse, Weise targets the mundane viciousness of everday hypocrisy like a heat-seeking missile.” Jillian Weise is the author of two previous poetry collections, The Amputee’s Guide to Sex, which was reissued in a tenth anniversary edition by Soft Skull Press in 2017, and The Book of Goodbyes (BOA Editions, 2013), which won the 2013 James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets and the 2013 Isabella Gardner Award from BOA Editions, as well as the speculative novel, The Colony (Soft Skull Press, 2010). She hosts a series of online videos satirizing literary ableism under the persona Tipsy Tullivan.

Jillian Weise, author of Cyborg Detective.

1. How long did it take you to write Cyborg Detective?

I’m still writing it. One of the poems in the book, “Attack List,” continues on Twitter. Since I am an actual cyborg—and not a tryborg who writes about or with machines while stuck in the ontological position of pure human—I make cyborg poems. What is a cyborg poem? I don’t know yet. It’s certainly not Fluxus, not Flarf: Those are tryborg poems. Maybe it’s a poem that jumps from page to screen and never ends. Or a poem that hacks the DNA of the short story “Cathedral” by Raymond Carver. Or a poem that glitches on Dickinson’s #745 (“Renunciation—is a piercing Virtue”). Or a poem that renounces esteemed keywords. Those are all poems in the book. But I lay no claim to defining the genre. We cyborgs are just getting started.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I internalize a lot of static from nondisabled writers and nondisabled literary conventions. When I’m writing or making, sometimes the static interrupts: This is gimmick. This is trick. This is too mean. Too much. Here’s another interruption that, for years, I believed: The writer’s ability or disability is irrelevant to art. So I had to uninstall all that and trust my crip and queer instincts.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Tonight, in my office, I figured out how to place the poem “Confession” at Dateline NBC, the New Yorker, True Crime Daily, Variety, VICE News, W Magazine, and WIRED all at once. I’m into guerrilla practices and code-as-accommodation and getting in sideways. It is not very different than daily life for us disabled writers. We often get into a building—whether restaurant or reading—through a side door or a back alley.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

Peter Conners, publisher of BOA Editions, accepted the manuscript a while ago and said something like, “Now that you have the security of the contract, go and write whatever you want and make whatever you want.” It gave me an unexpected jolt toward new forms.

5. What are you reading right now?

I just finished an article titled “Algorithmic Disability Discrimination” by Mason Marks and it is bleak, so what else? I loved “Possibilities in Cyborg (Cripborg) Bodies” by Mallory Kay Nelson, Ashley Shew, and Bethany Stevens. I’m in the middle of Sophie Collins’s Who Is Mary Sue? The poems are brilliant.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I cannot name only one. If I could revise The Norton Anthology of Poetry, it would include the openly disabled poets Hazel Hall, Josephine Miles, Larry Eigner, June Jordan, Pat Parker, Laura Hershey, and Constance Merritt. Then I’d ask the poets Raymond Antrobus, John Lee Clark and Meg Day to confirm that it’s basically a Hearing anthology. Norton has just published About Us: Essays From the NYT Disability Series, expertly edited by Peter Catapano and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson. I should add that I’m biased; I’m in the anthology. So I imagine Norton is already remedying the erasure of disabled and Deaf writers in their other anthologies.

7. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

The answer to this question is top secret.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

I have this recurring fantasy that I’m born disabled five hundred years from now on a comet with tons of disabled people and we all have healthcare and none of us has to set up a GoFundMe and we all write poems and none of us has to explain plastic straws to anyone. Sometimes the discourse on disability infringes on my imagination. The discourse includes things like the plastic straw debate, the latest book by a mother-of, father-of, thief-of disabled person and all the ableist devotion to diagnosing Trump with a mental illness. There are far more fascinating conversations we could be having on disability. For the most part, we are not having those conversations in the public sphere.

9. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

The publishing industry should allocate 50 percent of its budget to finding and soliciting and publishing and promoting books by disabled and Deaf and neurodivergent writers until the moment when our books reach equity with all their books about us.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I return over and over to this passage—“I didn’t know it could be done. I had never seen it done. I had, in fact, been told it couldn’t be done”—from Julia Alvarez’s “On Finding a Latino Voice.”