This week’s installment of Ten Questions features John Elizabeth Stintzi, whose debut novel, Vanishing Monuments, is out today from Arsenal Pulp Press. When the assisted living facility call to inform Alani Baum that their mother’s dementia has worsened, they immediately pack their car and begin the drive north from Minneapolis to Winnipeg. Alani ran away from Manitoba and their mother nearly thirty years ago, but something tells them if they don’t go back now, they never will. Moving back into their mother’s empty home, Alani is confronted with difficult memories. A photographer, they wrestle with how to hold onto this place, whether and how to document its rooms, and when to let go. Alani has “a history of doing things far too late, of running from one burning building into another’s sparking start,” but they persist all the same. “Vanishing Monuments is a beautiful portrait of disassociation at once between countries, family, gender, identities,” writes Joshua Whitehead. “An absolute monumental achievement of a first novel.” John Elizabeth Stintzi is also the author of a poetry collection, Junebat, which was published by House of Anansi Press in April. Their writing can be found in Ploughshares, Kenyon Review, Black Warrior Review, and the Malahat Review, among other outlets. Born and raised in northwestern Ontario, they are the recipient of the RBC Bronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers, administered by the Writers’ Trust of Canada.

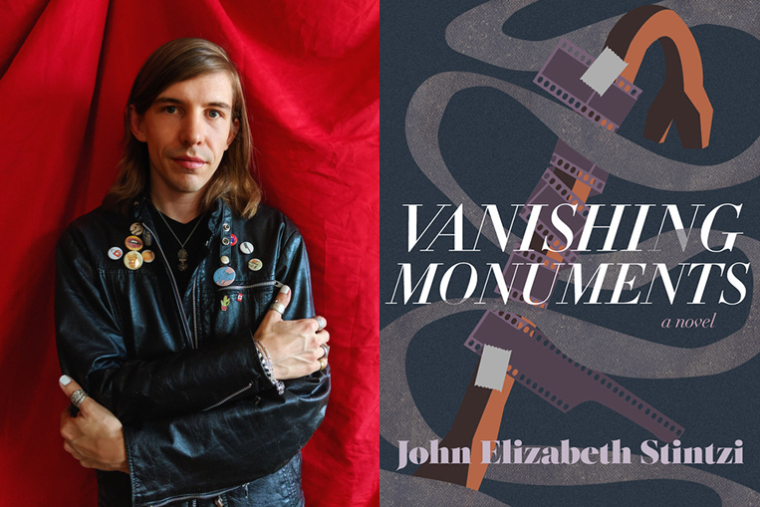

John Elizabeth Stintzi, author of Vanishing Monuments. (Credit: Melanie Pierce)

1. How long did it take you to write Vanishing Monuments?

I technically began writing it in the spring of 2014, back when it was a short story that refused to end, but I didn’t really start treating it as a novel until the summer of 2015. So the intense, intentional work of writing and rewriting the novel took about four years—with many setbacks along the way.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

It took me a very long time, and many iterations, to find the form of Vanishing Monuments. Many earlier attempts at writing it—after it failed to be a short story—were far more experimental than the final novel. I tried writing the novel as a series of letters-never-sent, as an artist’s journal, and as various other more conventional forms that fell apart before I could finish a draft. Once I learned about the mnemonic technique “the memory palace” in graduate school, I had a eureka moment. I realized that technique—and Alani’s mother’s house—could be used as the blueprint to structure the narrative, and I was finally able to tell the entirety of Alani’s story.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write mostly at home, either on our tiny dinner table or at my desk in the sunroom—a sentence that makes our apartment sound significantly fancier than it is. I mostly write before noon, because that’s usually when my mood is lightest and when I’m the most caffeinated. As the day goes on it gets more difficult to start writing, as often I’ll have darkened from the fact that I’ve not yet written. It’s easy to convince me to feel hopeless.

If I’m working on a project, and I’m immersed in it, I can write every day with ease, unless I’m teaching or otherwise occupied. I thankfully work pretty part-time/sporadically these days, which gives me many flexible days in a week. That said, I’ve been having a bit of a dry spell over the last year between teaching and the editing I had to do with Vanishing Monuments and Junebat—my poetry debut, which is also out this season—and since most of the writing work I need to do are revisions of my second and third novel manuscripts. It’s always a little harder to get excited about revision, but I’m working on it, and I’m hopeful.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading my partner’s novel draft, which is always an exciting time, and also Ivan Coyote’s new Rebent Sinner and Hazel Jane Plante’s Little Blue Encyclopedia (For Vivian). Next on my list is Sarah M. Broom’s The Yellow House.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I recently read Karen Tei Yamashita’s I Hotel, which came out in 2010 but was just rereleased by Coffee House, and having finished it I was instantly angry that it took ten years for me to discover that book. Yamashita has obviously published a lot of books, which I’m now starting to get into, but I Hotel completely blew me away and I know I’ll be thinking about it for a very long time. More people need to find her, and especially I Hotel, which refuses to be irrelevant despite being set in the sixties and seventies. Aside from Yamashita, I’ll add T Fleischmann as someone who deserves a wider audience, because their book Time Is the Thing a Body Moves Through is one of the finest and most exciting nonfiction books I’ve ever read.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Probably my ability to balance working and writing. As I said earlier, the last year has been a challenge to my writing practice, since in the fall I was teaching three courses while I was also editing and proofing both of my books, and this spring I’ve been getting caught up in marketing. It’s been a challenge finding a routine in the irregularity of this new life I’m living. These impediments are compounded, of course, by my depression, which has always been and will always be the most indefatigable impediment I face.

7. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I’d love to have more limited book advances for bigger writers—who will make money hand-over-fist in royalties, anyway—in favor of funding more risk-taking projects, specifically with under-privileged writers, in particular, trans femmes of color, who are the least represented in publishing, and not because they don’t write. I’d also love to see cultural shifts happen in publishing houses that would allow people of color and other marginalized people to actually be able to create long-term careers in publishing, which I believe would have to be achieved by paying people in publishing a living wage, which could be accomplished by taking strides to decentralize the industry to cities that have affordable costs of living.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Vanishing Monuments, what would you say?

You have no idea how much this book is going to change your relationship to your life. Don’t be shocked when you realize that despite the fact that you tried to write a character that was pretty different from you, all you really did was write yourself.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

For a majority of my work, especially my short fiction, my partner, Melanie, is my first reader, alongside a select few other trusted friends, but for novels specifically my friend Tony Wei Ling, the managing editor and a fiction editor for Nat. Brut, has been instrumental in giving me thoughtful and challenging feedback. I’ve been lucky to work with him both on an early draft of Vanishing Monuments as well as the surreal novel I’m currently working on, which is either going to be my second or third. His readings have been truly transformative for both books and he always pushes against the shortcuts I tend to naturally take in writing.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Write what you do not know, which I think is particularly helpful because—not to sound too much like Socrates—I’m not really convinced that anyone knows anything. Also, pay attention to your verbs.