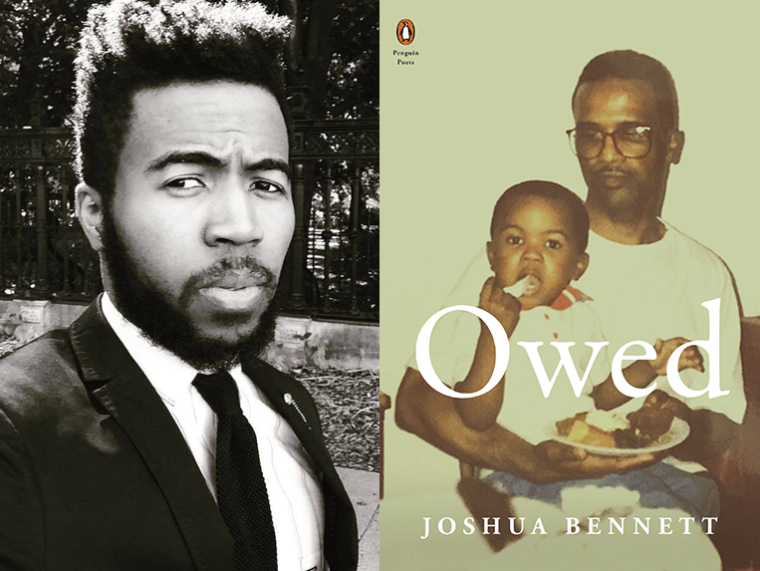

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Joshua Bennett, whose second poetry collection, Owed, is out today from Penguin Books. In Owed, Bennett covers immense territory in precise and nimble lines. Experimenting with the resemblances between images and words—“owed” and “ode,” for instance—he constantly discovers new angles to his subjects, whether tokenism, police violence, and reparations, or barbershops, school buses, and the plastic cover on his grandmother’s couch. Each object, place, or history is always more than itself, and Bennett models how to revel in the joy of that multiplicity. “How good it feels,” he writes. “To see this many people dancing / in a city best known / for its casual indifference.” Each poem in Owed is a prism for both truth and transformation. “This book is part of a breathful, bodied fight for Black life,” writes Aracelis Girmay. “I am emboldened and sharpened by Bennett’s genius and by his love made plain across each of these shimmering pages.” Joshua Bennett is the author of a previous poetry collection, The Sobbing School (Penguin Books, 2016), and a book of literary criticism, Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man (Harvard University Press, 2020). He holds a PhD in English from Princeton University and an MA in theater and performance studies from the University of Warwick. He teaches English and creative writing at Dartmouth College.

Joshua Bennett, author of Owed.

1. How long did it take you to write Owed?

I wrote the bulk of Owed between 2016 and 2019. I was finishing graduate school at the time and had just started a three-year term at Harvard in the Society of Fellows. The book is primarily the product of those years spent traveling between Cambridge, New York City, and various venues across the country, reading poems at middle schools, high schools, and colleges, trying to stretch my voice a bit. I was finishing another book at the same time—Being Property Once Myself, which was published by Harvard University Press earlier this year—and I wanted the poems to reflect the energy of the Black social life I theorized in that book, though in what felt like a very different register. I didn’t want to lose any of the music in the dance between poetry and theory.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Probably putting together the “Reparation” sequence. Doing so required me to spend real time with matters that I have explored elsewhere, though not quite with the same level of intensity. Writing on my father’s battle with stomach cancer, for instance, demanded I revisit one of the more difficult times in recent memory. The collection, in a sense, begins and ends with him. He both appears on the book cover and within the world of the final poem. So consciously meditating at length on that period—as well as the question of what calling a poem about the experience “Reparation” meant for the stakes of the collection as a whole—was complicated. Is it clear what I mean? I had to sit with the fear and let it talk to me. And talk through me as well. Then I had to realize that that thing, that fear, wasn’t going to go away without some more work, and that I still had to get on with finishing the book. All of the poems in that sequence are like that in one way or another. Writing about reparations, my time in therapy, my mother, my father’s illness, required me to stay still and not run from the occasion that brought me to the page.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write every day. Not always poems though. Fairly often, at present, I’m mapping out ideas for new research projects, editing talks in progress, and working on this pair of genre experiments that have been on my mind for years now. I used to write each morning at the dining room table, but recently promised my wife that I’m going to stop doing that, so I’m going to stop doing that. In an effort to break the habit, I bought a desk earlier this summer and look forward to building up a routine of writing there.

4. What are you reading right now?

Cheryl A. Wall’s On Freedom and the Will to Adorn. This alongside Sylvia Wynter’s The Hills of Hebron and James Baldwin’s One Day When I Was Lost.

Additionally, a week or so ago I picked up Corduroy by Don Freeman for my son who’s on the way and thoroughly enjoyed rereading it. I hadn’t held a copy of that book for well over two decades. It now holds a place of prominence in our home.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I always answer this question with some variation of “June Jordan,” because it’s true. But I’ll also add to this list Christopher Gilbert, Conrad Kent Rivers, and Wanda Coleman—both her poetry and her prose.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

I’m not sure that I have any worth mentioning. My own vulnerability to distraction, perhaps. I’ve written for as long as I can remember and in all sorts of situations. I can write in a window of several minutes or an afternoon where there’s not much on the immediate to-do list—however rare as of late. I’m thankful to have this sort of space. I do my best not to take it for granted.

7. What trait do you most value in your editor (or agent)?

Rigor. Imagination. Thoughtful, meticulous, courageous editors are a dream. The best ones I have ever worked with have always taught me something new about myself, about my habits of mind or unknown strengths. My collaborations with them have been nothing short of transformational in this way. Gifted editors are also educators of a certain kind, is what I’m trying to say. They open windows in us.

8. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I’m not entirely sure what constitutes a writing community for your readership; mine is mostly friends I made in school, at poetry slams, and via sharing videos on the internet. I love those people and wouldn’t change anything about them. My experience with the publishing industry is fairly limited, but what’s clear to me, even at this early stage, is that there are very few Black agents, editors, and decision-makers more generally within it. Ever since I started out, I’ve found this fact to be rather startling. That won’t change without a prolonged, good-faith commitment at every level of the industry.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

My most trusted reader of my work is probably my friend, Jesse. He’s not a liar.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Greg Pardlo told me: “Don’t be afraid to use of all of your Englishes.” Saidiya Hartman said “You must listen to the language that Black people have used, historically, to describe ourselves.” At Princeton, Imani Perry and Eddie Glaude once enjoined a room full of us to commit to the beautiful sentence. Whenever I sit down to write, these pieces of wisdom are working through my mind. They are my armor and incantation.