This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Joy Castro, whose new novel, One Brilliant Flame, is out today from Lake Union. This multilayered tale offers a window into a little-remembered event in U.S. history: the 1886 Great Fire of Key West, which ravaged the bustling Cuban immigrant enclave that lived on the island off the tip of Florida. The fire changes the lives of six friends, whose first-person accounts create a portrait of this distinctive community torn between two worlds: the United States and their homeland that is fighting for independence from Spain. Dominated by prosperous cigar factories, where workers employ educated lectores to read them books and newspapers as they work, Cuban Key West is a world both tight-knit and hierarchical, where skin color, class, gender, and family background affect one’s place in the social ecosystem. Through the eyes of these six friends, this now-gone world comes to life as much as the personal drama that unfolds among the narrators as they explore their identities and move toward their goals, making One Brilliant Flame a coming-of-age narrative as much as a historical novel. Ana Menéndez calls One Brilliant Flame “a stunning work of the imagination—a brilliant evocation of the way war, exile and freedom defined the Cuban nation from the start.... A spectacular achievement that continues to resonate beyond the book’s close.” Castro is the author of four other works of fiction, including the novel Flight Risk (Lake Union, 2021), as well as a memoir and an essay collection. A former writer-in-residence at Vanderbilt University, she is currently the Willa Cather professor of English and ethnic studies (Latinx studies) at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, where she directs the Institute for Ethnic Studies.

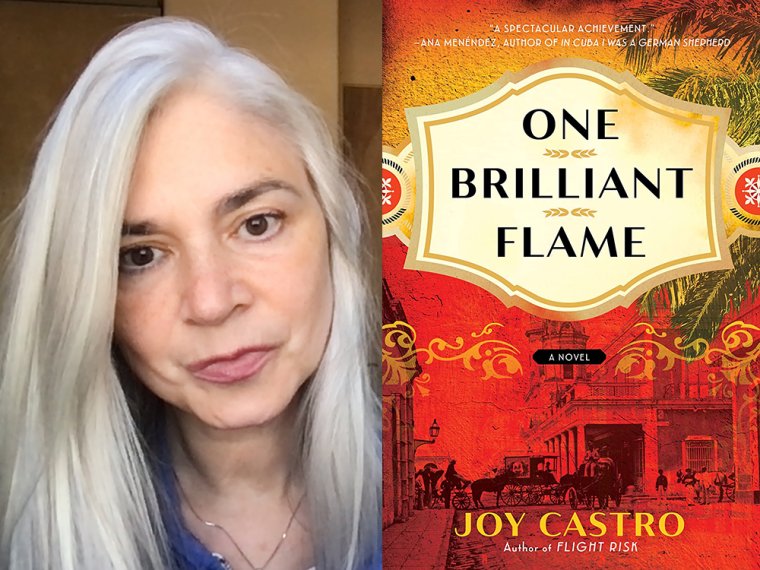

Joy Castro, author of One Brilliant Flame.

1. How long did it take you to write One Brilliant Flame?

Just under three years. The concept struck me when I learned about the real-life 1886 Great Fire of Key West at a research institute in Tampa in May 2019, but I had to finish writing another novel, Flight Risk, before I could complete the necessary groundwork for One Brilliant Flame and really start drafting. I turned in my final revisions in February 2022.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Plotting. It’s not my forte, so I always have to work really hard at it, because I want the story to be propulsive. The other challenging thing was quickly digesting an immense amount of historical information, then writing in a sleek, natural, fluid style.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

It varies wildly. I mostly like to be alone and very quiet, but I’ll write in coffee shops, bars, or even at concerts—for some reason good lines pour into my mind when music’s blaring. I write on planes and in airports if that’s what my schedule requires. Anywhere. Any time of day. I love to write in bed in the mornings before I interact with anyone or read e-mail, to write with just my naked dream-brain. But that’s a luxury. I work as a full-time, year-round academic administrator in addition to teaching regularly, so I just do what I can. The writing’s best when I don’t force it—when I just listen for the voices and show up.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading the novel Forbidden Notebook by Cuban Italian writer Alba de Céspedes, first published in Italy in 1952 and newly translated by Ann Goldstein, who is revered for her translations of Elena Ferrante’s work. Forbidden Notebook is the story of a forty-three-year-old petit bourgeois, working housewife, Valeria Cossati, who—on a whim, and stealthily—acquires a notebook. When Valeria starts secretly recording her honest observations, the livable fictions she’s believed about her friends, her adult children, her office job, and her marriage all begin to crumble. It’s devastatingly good.

Alba de Céspedes was a feminist journalist, novelist, and screenwriter who was imprisoned for her antifascist work in Rome before and during World War II. She was also the granddaughter of 19th-century Cuban anticolonial independence hero Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. I got incredibly excited when I first saw her name (in a tweet last fall by Merve Emre), because I hadn’t known he’d had a descendant who was a writer. Forbidden Notebook will be out this month from Astra House.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

In general, the writers who’ve most influenced my work are Katherine Mansfield, Jean Rhys, and Sandra Cisneros: precise, concise tellers of shattering truths about gender, class, and race whose best stories sing like poetry and work like jabs to the solar plexus, leaving you gasping. In high school in West Virginia, I stumbled across Mansfield’s story “A Cup of Tea” (1922) in an old anthology and have never been the same. It opened a door. I wrote my master’s thesis on Wallace Stevens and my doctoral dissertation on Margery Latimer, so I apparently have a thing for modernists, especially those who haven’t gotten the lion’s share of critical attention.

For One Brilliant Flame in particular, which relies on perspectivism, Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine and William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying were formative for me—how deftly they each balance a panoply of characters’ voices. And Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye: the aesthetic and sociopolitical boldness of that book, the way it just brilliantly leaps and assumes the reader will be able to follow.

I’ve always loved Middlemarch too—that thickly described portrait of a whole community as well as of a few key intimate relationships and individuals—but for this book’s particular material, a third-person POV would feel way too static to me: too God’s-eye, too morally settled. One Brilliant Flame’s six flawed and vulnerable first-person narrators keep it moving. I love the fruitful friction created by the juxtapositions of their differing versions of their shared world.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of One Brilliant Flame?

Who knew how much I’d love writing the interior lives of men?! It felt very brash. I was also surprised to find that writing in six distinct voices actually felt very comfortable and fluid, very natural and effortless. Only when I stopped to think about it did I become nervous about writing from different gendered, classed, and raced perspectives—so I just had to accept the possibility of horrible blowback if I failed to pull it off. Mentally making friends with the potential for humiliation and defeat was incredibly liberating. I like taking risks.

7. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

One Brilliant Flame is set in Key West, where my grandparents and cousins lived when I was a child, so my earliest memories associated with the book involve swimming at the beach, fishing off the docks with my father, and eating mangos and avocados from my grandmother’s backyard trees. It was a pleasure to let all the sensuous warmth, fragrances, and delicious foods of Cuban Key West suffuse the novel. I put my whole soul in.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started One Brilliant Flame, what would you say?

This will stretch you. Get ready to leap.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

A tremendous amount of research! I’d always been curious about my forebears’ 19th-century experience in the Cuban enclave in Key West, but no one in my family ever talked about it. It was a complete mystery to my generation—and that cultural moment was definitely never covered in any history courses I encountered in high school or college.

When my father died by suicide in 2002, we found among his things some bound, printed copies of our great-grandfather Juan Pérez Rolo’s eyewitness account of having come from Havana as a child in 1869 to Key West, where he grew up as part of the anticolonial rebel community and became a newspaper editor and printer. We also found a 1918 collection of poems by my grandfather Feliciano Castro, who—unbeknownst to me at that time—had been hired as a lector when he’d first arrived in Key West as a young man: crumbling documents the color of tea stains, in Spanish.

At that point, I didn’t even know what lectores were. They read the news, political theory (Karl Marx, Mikhail Bakunin), and novels—great humanist novels by Victor Hugo and Charles Dickens, adventure novels by Alexandre Dumas, and many others—aloud to the workers in cigar factories. The cigar rollers hired, paid, and fired the lectores, so the workers controlled the content, and they provided instant feedback to the lectores (by applauding or not—rapping their cigar knives on the wooden worktables). Because lectores were educated men (almost without exception) who were often also simultaneously writing for the Cuban press, there was a strong labor-driven influence on what was published.

The structure of this fascinating, unique circuit really has no cultural equivalent: workers aurally getting a university-level education in politics and literature while they performed manual labor, and in turn having a tremendous impact, through their influence on the writing of lectores, on the political and cultural conversations of the day.

But I didn’t understand any of that at the time of my father’s death. I didn’t yet know the larger social and geopolitical history into which those isolated documents by my grandfather and great-grandfather fit. I didn’t comprehend their significance, and I let them languish for many years while I worked on other things.

In 2019, I was thrilled to stumble across a monthlong National Endowment for the Humanities research institute specifically about the nineteenth-century Cuban émigré communities of Florida and their anticolonial fight against Spain. It was my dream course, and I went. There at the University of Tampa, we read over seven-hundred pages of published scholarship on the era and heard lectures by a dozen scholarly experts. It was utterly revelatory. My brain was on fire.

Afterwards, I dived even deeper on my own. In One Brilliant Flame, the acknowledgements thank fifteen different historians without whose work I could never have written the book. My learning curve has been profound, and to be able to bring this beautiful, tumultuous, utopian, anticolonial, antiracist period of history to life for readers today is a dream come true.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

“No one can stop you.” I can’t say whether it’s true or not, but it’s an excellent thing to believe.