This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Julia Elliott, whose story collection Hellions is out today from Tin House Books. The eleven stories in this collection leap from the occult to the comic, from the horrific to the wondrous, as earthbound characters yearn for the otherworldly. A nun works on a forbidden mystic manuscript in a plague-stricken medieval convent. In rural South Carolina, an alligator named Dragon becomes a pet for a precocious twelve-year-old. At a feminist art colony in the North Carolina mountains, a group of mothers confronts the supernatural talents their children have picked up from a pair of mysterious orphans who live in the forest. Carmen Maria Machado says, “Every sentence drips and unsettles, every character lusts and schemes, every landscape is alien and forbidding…. I am obsessed with these lush, feral stories.” Julia Elliott is the author of the story collection The Wilds (Tin House, 2014), a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, and the novel The New and Improved Romie Futch (Tin House, 2015). Her work has appeared in the Georgia Review, Tin House, Conjunctions, and the New York Times. She has won a Rona Jaffe Writers’ Award, and her stories have been anthologized in Best American Short Stories and Pushcart Prize: Best of the Small Presses. She teaches English and Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of South Carolina and lives in Columbia with her husband, daughter, and five hens.

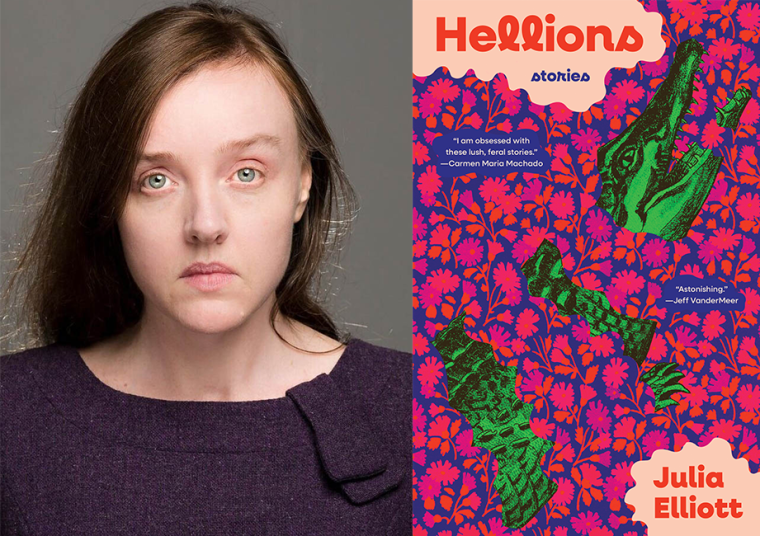

Julia Elliott, author of Hellions. (Credit: Forrest Clonts)

1. How long did it take you to write Hellions?

Although I have steadily written and published short fiction since releasing my first collection, The Wilds (Tin House), in 2014, Hellions didn’t come together thematically until I realized that my story “Hellion,” published in the Summer 2018 issue of the Georgia Review, held the conceptual key for wrangling a wild array of tales into a thematically unified book. The earliest story in the book, “Erl King,” was published in Tin House in Spring 2018, and the latest, “The Maiden,” appeared in Reactor in February 2025. Though I consider every story I’ve written since 2014 to be part of the process of refining this collection, the stories within it represent about seven years of writing and publishing.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The short story form offers me a way to indulge my obsessions and experiment with various genres and narrative modes. Since I don’t write stories with a larger thematic arc in mind, my biggest challenge involves finding a central concept that brings the various types of stories together in a meaningful way. In 2023, when I realized that “Hellion” was the natural title story for this collection, I finally found a way to unify what had seemed like a hodgepodge of strange tales. Each story in my new collection captures the special essence of the hellion, a word I heard often while growing up in rural South Carolina. A hellion is a rebellious, impish creature—often a child—who disrupts the norm and sometimes causes all hell to break loose. As the word implies, hellions may hail from the underworld and have the Devil in them, but they are also earthbound characters who long for the otherworldly.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Since I’m a full-time professor, I juggle writing, teaching, and parenting a teenage daughter, so that leaves me with anywhere between four and six mornings a week to write, depending on my schedule (I don’t teach during the summer, for example). Ideally, after a good night’s sleep, I spend two to three morning hours drinking coffee and writing in my home office. Like many writers, I’m always thinking about my work. I often come up with ideas and breakthroughs while walking, biking, or gardening.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just started The Antidote (Knopf, 2025) by Karen Russell, one of my favorite writers. This novel offers her usual blend of genre innovation, gripping narrative, inspiring lyricism, and engaging characters. So far, I’m amazed by the scope and heft of her vision in this “Dust Bowl epic.” In the first chapter, I was instantly transported to Uz, Nebraska, by a prairie witch with the power to unburden people of disturbing memories. The Antidote underscores how the witch figure is both eternal and “historically specific” to various locations and eras. In Hellions, half of my stories explore the uncanniness of girlhood, while others tap into the archetypal potency of the witch, women deemed hellions by society—odd, estranged beings who lurk along the borders between the real and surreal. As a horror fan obsessed with female monsters, particularly witches, I’m smitten with Russell’s prairie witch, for she is both a universal figure and a distinct character produced by a singular, astonishing imagination.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

There are so many amazing writers who don’t get the attention they deserve, but I’m going to focus on one that has had a profound effect on Hellions. Although Surrealist Leonora Carrington has emerged as a prominent painter since her death in 2011, her writing is still not as widely known as it should be. The best way to experience Leonora Carrington’s brilliance is to plunge into her world through her paintings and her writing, becoming obsessed with her astonishing life story, her deeply feminist take on Surrealist occultism, and her abstruse yet playful fiction. Though her writing may seem like innovative absurdism, if you understand the “total occultation of Surrealism” that happened after World War II, then you can dig deeper into the arcana of her work. Susan L. Aberth’s Leonora Carrington: Surrealism, Alchemy, and Art (Lund Humphries, 2010) is a great introduction to her life and paintings. After reading that, it becomes clear that Carrington’s writing, like her paintings, offers a rich, idiosyncratic mythology to decipher. The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington (Dorothy, a publishing project, 2017) and her novel The Hearing Trumpet (St. Martin’s Press, 1976) are not only playful Surrealist narratives, but also profound explorations of various hermetic philosophies. Diehard Carrington fans should also read her memoir Down Below and The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington (Virago, 2017) by Joanna Moorhead, Carrington’s cousin.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Getting a decent night’s sleep is the most important factor in my ability to write well in the morning. If I get a bad night of sleep, no amount of coffee or exercise can coax my foggy brain into the alertness required to write, plot, strategize, and/or revise. I usually have one or two mornings a week that are destroyed by poor sleep.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

When I first met with my brilliant editor Elizabeth DeMeo, she told me that short story collections are experiencing a small renaissance. I will always write short stories no matter what’s going on with the literary market, but it’s great to know that people are currently interested in reading them.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Hellions, what would you say?

When writing short stories, don’t let the desire for thematic unity stop you from chasing odd obsessions and trying new approaches with genre, characterization, point of view, and other formal elements. It’s best to have a wide array of imaginative and daring stories to choose from when the time comes to compile them, even if you must wait longer for the “right” book to come together.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Hellions?

Teaching two college courses I designed for the University of South Carolina Honors College has allowed me to not only formalize the study of topics that fascinate and inspire me, but also to learn from my students in a collaborative environment. My course Monstrous Mothers, Diabolical Daughters, and Femme Fatales: Gender and Monstrosity in Horror Films is a service-learning class that focuses on the depiction of female monstrosity in horror. In addition to studying a wide range of films, I cocurate a community feminist horror series that my students market. In another course that revolves around the theme “Politics of the Marvelous,” we tackle three interconnected units: the social and political circumstances surrounding Mary Shelley’s creation of Frankenstein; “Surrealism and the occult” featuring Leonora Carrington, Max Ernst, Remedios Varo, Claude Cahun, Leonor Fini, Frida Kahlo, Jean Cocteau, and others; and finally, contemporary horror works created by African Americans and artists from the African diaspora.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I have this fantastic quote from George Saunders about how no genre is “off limits” to writers as long as they follow Faulkner’s idea that profound literature explores the “human heart in conflict with itself.” I can no longer find this interview on the internet, however, so I’m wondering if Saunders visited me in a dream or possessed me during a bout of automatic writing. A 2015 conversation between George Saunders and Jennifer Egan in the New York Times Magazine also contains good advice about blending speculative elements with realism. Saunders says: “When I’m writing, I like to just allow myself one exaggerated or impossible element. So in something like ‘The Semplica-Girl Diaries,’ the only unreal thing is the fact of the existence of these ‘Semplica-Girls’ —which are these living lawn elements: third-world women being paid to hang on a wire in one’s yard. Other than that, it’s our world. Therefore, whatever energy comes off the story is about our world…. This is the Kafka model, I think: Other than the fact that Samsa wakes up as a bug, ‘The Metamorphosis’ is running on fairly realist energy. That Prague works about the same as the real Prague of that time, except: guy turns into a bug.”