This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Justin Torres, whose new book, Blackouts, is out today from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. In this matryoshka doll of a novel, a young man visits an older man from his past who, now on his deathbed, wishes to bequeath a trove of documents to him. The primary text he offers, Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns, is a real book published in 1941 that collects narratives of queer men and women. Along with other archival images and records, pages from Sex Variants punctuate the novel, their sentences strategically struck through with black ink in the manner of erasure poetry. Indeed, the spare, leftover language functions as verse, essentially rewriting the psychology book by centering queer subjectivity while raising questions about the nature of institutional “knowledge” and the harm it can cause, particularly to marginalized populations. Meanwhile the two men tell each other stories, filling each other in on their shared and separate histories—a process that is particularly confounding for the younger man, who suffers memory lapses, or blackouts, which he hopes his companion may be able to help him better understand. Alexander Chee praises the novel: “Blackouts gives me what I read fiction for, what I read for at all―the sense of a brilliant mind creating a puzzle in the air in front of me, all intelligence and surprises.” Justin Torres is the author of We the Animals (Mariner Books, 2012), which won the Virginia Commonwealth University Cabell First Novelist Award, was translated into fifteen languages, and was adapted into a feature film. His writing has appeared in the NewYorker, Harper’s, Granta, Tin House, the Washington Post, and elsewhere. He teaches at the University of California in Los Angeles.

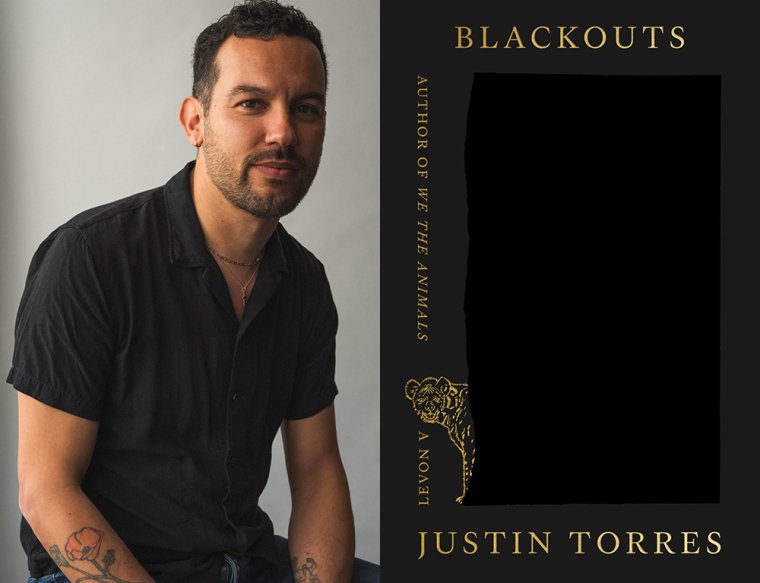

Justin Torres, author of Blackouts.

1. How long did it take you to write Blackouts?

That’s a tough question to answer. It’s been over a decade since my last book, We the Animals, came out. I like to think everything I was reading, pondering, dreaming, and writing in that decade has found its way into Blackouts. Mostly I was stretching to become a different kind of writer, and that took time.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The structure. The image permissions. Allowing myself other, more metaphorical kinds of permission. The exposure. I could go on. It’s a challenging book.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I don’t have any sacred ritual. My boyfriend and I were in a long-term, long-distance relationship, so when the teaching term ended, I would head to Oxford, England, and spend most of my summer there. Summer generally allows me to get more done. That’s also where I spent the Covid lockdown, and it was in those quiet, strange days that I finally finished the book.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’ve just recently pivoted to read the finalists for the National Book Award—in various genres—whose books I hadn’t yet read. But I am also reading Touching the Art by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, Greenland by David Santos Donaldson, and some advance copies of forthcoming books: The Great Divide by Cristina Henríquez and The Long Run: A Creative Inquiry by Stacey D’Erasmo, about artistic stamina, among other things.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Blackouts is, in many ways, a book about reading—in the straightforward literary sense of that word; in the sense of reading people, situations, images, history; and in the queer sense of reading (and being read). The book directly references a number of texts and writers: Manuel Puig, Jaime Manrique, Jan and Zhenya Gay, Toni Cade Bambara, Juan Rulfo, Kathleen Collins, Heather Love, Patricia Gherovici, Jesús Colón, Jean Genet, Tennessee Williams, Emma Goldman, and many, many more.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Blackouts?

Finishing the book. There were so many days (most days?) when I didn’t think I would, or could.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

My editor, Jenna Johnson, was so involved in all matters spiritual and practical, I really don’t know where to begin. She’s on every page. We would have these long phone conversations when I felt I was truly lost in the woods, and she would describe to me what I was up to, what the pages were doing, and what else they might do. She was my editor for We the Animals, and we’ve become incredibly close over the years we’ve worked together—I mean, it must be something like fifteen years at this point! I could go on forever about how fortunate I feel to have her by my side; it’s one of the most important relationships in my life, no hyperbole. The only pressure I ever felt from her was to be honest to the vision I had for the book, not to concern myself with anything else—the possible reception, for example, or how long I was taking to finish, or whether or not I’d be able to include images or use colored ink, and on and on. Her constant refrain was, “Just do what you feel you need to do. Let me worry about the rest.” And so I did. I’m still probably allowing her to worry about much too much!

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Blackouts, what would you say?

I don’t know, this particular kind of question never makes much sense to me. My past self would not accept advice from my future self. We know us too well to trust one another.

But I know what my friends would say: Please don’t neurotically trash talk your own book to everyone you meet.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Reading. Researching. Reading more widely and more broadly. Seeking out people—like my man, my friends, mentors—who are smarter than me and generous enough to share what they’ve learned of the world. Rereading.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

Believe it or not: Slow down.