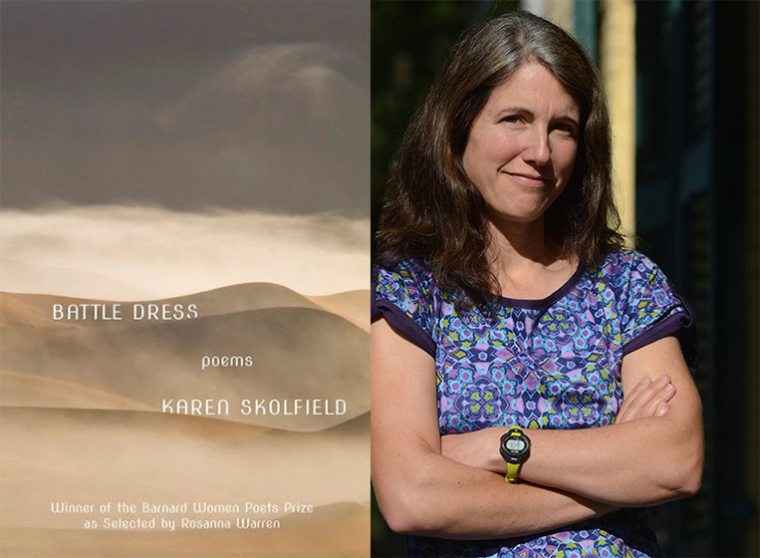

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Karen Skolfield, whose second poetry collection, Battle Dress, is published today by W. W. Norton. In Battle Dress, Skolfield, a U.S. Army veteran, offers a fierce yet intimate glimpse of a soldier’s training, mental conditioning, and combat preparation as well as a searing examination of the long-term repercussions of war and how they become embedded in our language and psyche. “A terrific and sometimes terrifying collection—morally complex, rhythmic, tough-minded, and original,” writes Rosanna Warren, who chose the book as winner of the 2018 Barnard Women Poets Prize. Karen Skolfield is the author of a previous poetry collection, Frost in the Low Areas. She teaches writing to engineers at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst.

Karen Skolfield, author of the poetry collection Battle Dress. (Credit: Michael Medeiros)

1. How long did it take you to write the poems in Battle Dress?

Most were written in the five years after my first book came out. A handful were written in grad school, not long after I finished my second enlistment.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Staying on topic. I’ve never had to do that before with poetry, and it meant I had both short-term and long-term goals in the writing stage. It was the difference between writing a poem I cared about and writing a book I cared about. Then, after Battle Dress was accepted, it was hard to go back to writing poems that were not about the military.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I get a ton of writing done at residencies. Battle Dress—plus many other non-military poems I snuck in—would not exist without my residencies at Ucross, Hedgebrook, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and Vermont Studio Center. But I can’t go away all the time, so I do at least one “30 poems in 30 days” per year with friends, plus I write on an irregular basis the rest of the year. If I hadn’t already been discharged from the Army (honorably discharged, thank you very much) I am sure they would kick me out now for my lack of discipline and my deep love of 8:00 AM wake-ups. I remain in awe of writers who manage a regular writing life. You write at 5:00 every morning? Whoa, I bow in your direction.

4. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I have three readers I lean on heavily: Brandon Amico, Kristin Bock, and Janet Bowdan, all poets. They see really different things and react in their own ways to my work: Brandon is over the moon when I write anything, but when it gets down to editing he pulls no punches. Kristin believes in my work before I ever do and convinces me that good things will come; she’s excellent at seeing the possibilities in poem intensity and ordering. Janet very kindly stomps on my poems and then offers ideas on how to rebuild them.

5. What are you reading right now?

I’m finishing Brandon Courtney’s This, Sisyphus from YesYes Books. Courtney is a poet and a Navy veteran and I’m in absolute awe of his lyricism and musical ear. It’s a book I’m both enjoying and learning from in terms of craft and how to build a book, how to make a collection of poems work together.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Janet Mock. She’s well known to adult readers, but her books should be required reading for middle- and high-school students everywhere. Redefining Realness is taught at my son’s high school and I am sure it has changed—and saved—lives.

7. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Battle Dress, what would you say?

I’d go back a ways and ask the seventeen-year-old, newly enlisted me to take notes, please, lots of them. I’d ask kindly, because I know what’s coming and she’s just so young. Battle Dress is invented, but it relies heavily on my seven years in the Army, and I’d love a better account of my enlistment than the pitch and yaw of memory, the few letters I managed to save.

8. What trait do you most value in a poetry editor?

As a poet, I largely take for granted how talented and efficient poetry editors are. What gets me in the gut is how kind they invariably are even as, I am sure, they are overworked. I’ve received the nicest comments and editing from literary journals—George David Clark and Cate Lycurgus from 32 Poems, and Don Bogen at The Cincinnati Review are recent examples in my world, but there have been so many others. Poets Rosanna Warren and Nancy Eimers, the judges who chose my two books for publication, wrote such nice notes and gave such thoughtful editing suggestions that I had to pause multiple times while reading.

Similarly, Jill Bialosky and Drew Weitman at Norton and the folks at Barnard College have taken great care and thoughtfully passed along all the congratulations and comments they’ve received about my book. You know, poet here, starving for praise, and they weren’t required to take the time out of their work days, but they did, and it means a lot. And when I got the style sheet and copy editing queries from Norton I got teary. Having top copy editors see and consider not just the drive of the poems but the structure, make sure every comma and capitalization was correct, was deeply touching. I was stunned—something I wrote had earned that level of care.

9. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Myself. The world is both really fun and really demanding and it’s hard to look away. Lately I can add some physical difficulties to this—neck, spine—that severely limit my time at the keyboard, but that just comes back to me, doesn’t it?

Wait. Everyone says this, don’t they? (Checks last zillion answers on the P&W website.) Yeah, pretty much. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could all just give ourselves up? Think of all the writing we’d get done!

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

It’s necessary to write terrible lines, awful drafts, half-hearted poems. Write ten in a row if needed. Throw pencils, get mad, take a walk. Swear off poetry, read a chapter of a post-apocalyptic novel, wash the dishes. Feel better? Back to writing. Repeat as necessary.

For some reason, this is advice I need to hear again and again. Every poem I write is either my delight or torment, a feather or a lash. But I don’t know how to be less invested, even in my poems that sound nonchalant to a reader.