This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kate Zambreno, whose latest novel, Drifts, is out today from Riverhead Books. The narrator of Drifts is a writer at work on a long-overdue manuscript. She lives an active creative life—she corresponds with fellow writers, photographs and documents obsessively, analyzes the work of Rainer Maria Rilke and Albrecht Dürer, and writes exquisitely of her terrier, Genet—yet the various pieces of her life seem to conspire against her most important work on the page. Taking long walks around her New York City neighborhood, she searches for a new way to talk about and make art. “What is the landscape you’re working in, I start to ask other writers…rather absurdly,” she says. “A better question to ask, though, than What are you writing? Or What is your book about?” Her questions, notes, walks—and a number of dramatic, unexpected disturbances—gradually give rise to a shift and new understanding. “Kate Zambreno’s writing is mysterious, unclassifiable, and yet intimate and familiar too,” writes Jenny Zhang. “Reading her is like looking through a kaleidoscope—the world is at once more beautiful and more terrifying.” Kate Zambreno is the author of several books of fiction and nonfiction, including Screen Tests, Heroines, and Green Girl. Her writing can also be found in BOMB, the Paris Review, and the Virginia Quarterly Review, among other outlets. She teaches in the writing programs at Columbia University and Sarah Lawrence College, and lives in Brooklyn, New York.

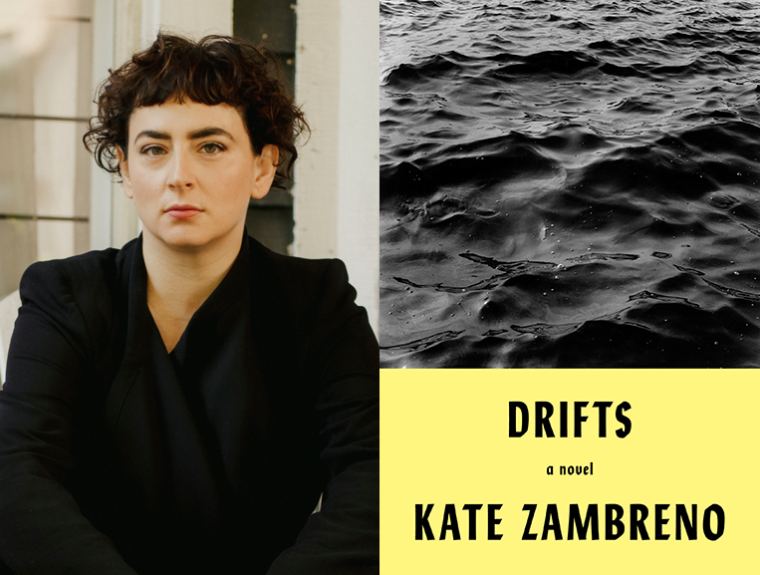

Kate Zambreno, author of Drifts. (Credit: Heather Sten)

1. How long did it take you to write Drifts?

I started writing through this elegiac, hungover period as soon as Heroines was published eight years ago in essays that were prodromal to Drifts. Soon after I moved to New York City, I began compiling the notes and journals that would later be the raw material for the novel. I’ve probably been intensely working on and revising the book for five to six years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

It was challenging to sell a novel to my editor, Cal Morgan, who was then at Harper Perennial, when it was just a concept, more of a longing for a potential book rather than anything materialized. Then I had to figure out what the book was and how to write it once I was under a contract. And then of course life got in the way and Drifts became about life getting in the way. I had to then sell this draft of what became quite a different book to Cal again once he moved to Riverhead.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

If you were going to ask the person who wrote most of Drifts, the answer would have been on train rides to teach class, and in my notebook in coffee shops, and during the summer and December when I’m not teaching, in concentrated periods of working in my office and lazing around in bed or on the couch. But the answer right now, with a toddler, is in periods of intense activity when I have a deadline, which is often why I give myself a deadline, and in notebooks in moments snatched while in bed or on the couch, and often not at all. I often don’t write much, but I try to at least think about my project or something relating to writing once a day, to confront it in some way.

4. What are you reading right now?

Moyra Davey’s Index Cards, an anthology of her essays and books that New Directions is publishing at the end of May—I love Davey’s intensely referential work, her essays that are about reading and the lives of others, both her written texts as well as her accompanying video works.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Sofia Samatar, who is one of the major correspondents within the world of Drifts. She is extremely respected within the fantasy world, but I wished everyone read her stories that read like essays and her nonfiction that reads like speculative fiction. Her recent nonfiction manuscript, The White Mosque, is as brilliant and as sui generis as anything by W. G. Sebald or Olga Tokarczuk.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

I know some might look at my life right now and answer “motherhood”—but I don’t think that’s it, actually. I think in some ways I’ve written more since becoming a parent than before, mostly because time has more meaning and weight to it now. The real answer I think is capitalism and the precarity that comes with it.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

The book has gone through many permutations on its way to being published. I think in the process of trying to get it published over the past two years, what has stuck with me is everyone’s reliance on the concept of “autofiction,” and reading Drifts within that context, which is a newly remodeled historical concept with which I don’t really connect. The tradition I see Drifts as existing within ranges from American New Narrative to French writers like Hervé Guibert or Marguerite Duras, or writers like W. G. Sebald or Robert Walser, or my contemporaries like Bhanu Kapil and Moyra Davey, rather than this contemporary trend of calling certain types of fiction that’s seemingly autobiographically-based as autofiction. One editor rejected the book by telling my agent he was bored with autofiction. Another actually, a male editor of a blue-chip small press, told me he was freaked out by the pregnant narrator, although maybe, he wrote, that could have just been him and his own discomfort. Yeah, maybe.

8. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I find this concept of “comps” or comparisons that I think I’m referring to in the previous question as pretty poisonous actually—that to get published by a larger press you must present your work in direct comparison with a work that’s been commercially and critically successful, preferably a bestseller. It waters down work to have it compared to everything else published recently, especially the onus on it selling well. I’m tired of everything being compared to what’s been out just the past five years, in general.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

My most trusted reader is my partner John Vincler, who always has given everything I’ve written a first read for the past fifteen years and who I can count on to say whether he thinks something is good or bad, interesting or not that interesting. He’s also a talented line editor.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

It sounds a little nutty coming from someone who’s been teaching writing for more than a decade, but I’m mistrustful of writing advice in general—which relates to my irritation that writers are now expected to be sages. But I have noticed that the writers who are willing to revise their work substantially are eventually able to get their work to do what they want it to, and to find someone willing to publish it.