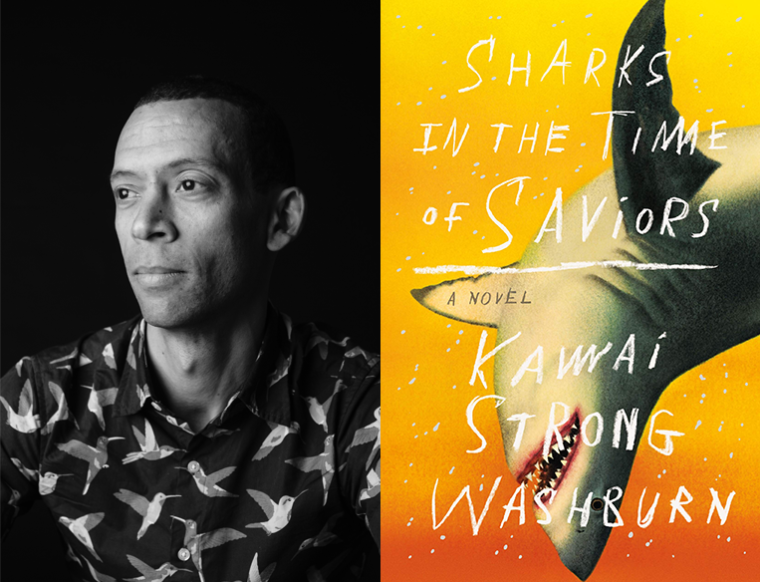

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kawai Strong Washburn, whose debut novel, Sharks in the Time of Saviors, is out today from MCD/FSG. When the Flores family is at its most vulnerable, ancient Hawaiian gods appear to intervene. Out at sea off the coast of Kailua-Kona, Hawai‘i, seven-year-old Nainoa Flores falls into the water, but is quickly rescued by a shiver of sharks that gently return him to his mother. The gathering of sharks is the first of many supernatural events that transpire around Noa and his family, and Washburn alternates between their different points-of-view to create a prismatic family saga. Shifting from Hawai‘i to the mainland United States and back again, Sharks in the Time of Saviors charts the family’s exile and pursuit of salvation, their bond to one another and to their home. “Sharks in the Time of Saviors is a lush, virtuosic novel with breathless scope and last depth,” writes Claire Vaye Watkins. “Kawai Strong Washburn’s vision is searing, his talent explosive, his heart beating loud on every page.” Kawai Strong Washburn was born and raised on the Hāmākua coast of the Big Island of Hawai‘i. His writing can also be found in Best American Nonrequired Reading, McSweeney’s, and Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading. He lives in Minneapolis.

Kawai Strong Washburn, author of Sharks in the Time of Saviors. (Credit: Crystal Liepa)

1. How long did it take you to write Sharks in the Time of Saviors?

It was ten years, or maybe longer, from the time I first pressed the keys on a keyboard until the words appeared on physical pages. The central image—a child being pulled gently from the water by sharks—had been in my head for a few years before that, so I’d been unconsciously interrogating it for some time.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Since none of the characters are consciously based on anyone I know, including myself, I had to create a set of characters completely out of thin air. They each needed distinct psyches and distinct voices, a challenge in itself. But an outgrowth of developing those voices was the challenge of how to represent Hawai‘i’s patois, commonly referred to as “pidgin,” in a way that I thought read well on the page and wouldn’t be too challenging for the reader’s eye, yet still captured the rhythm as best as possible.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

It’s changed over the years, from the time I was single and wrote whenever and wherever I wanted—ah, the halcyon days of productivity—to now, where I try to write every morning from about 5 AM until my kids wake up and the school day scramble starts, usually around 6:30 AM. But the kids keep getting each other and me and my wife sick, which means I’m never healthy enough to mortgage my sleep for writing. That has taken a huge toll on my productivity over the last six months or so.

4. What are you reading right now?

I work heavily in climate policy advocacy at the state and national level. So, one of the books I’m reading is Designing Climate Solutions: A Policy Guide for Low-Carbon Energy by Hal Harvey, an excellent technical guide to the policy options at our disposal for preventing the most catastrophic outcomes of climate change. There’s a lot we can be doing right now, if we focus our political attention and will. I just finished reading Red Panda & Moon Bear with my daughter. It’s an excellent graphic novel about two young Cuban American child superheroes that roam their Miami neighborhood in a series of delightful adventures. So much fun. Also, my wife and I read out loud to each other at night, and right now we’re reading Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age, which is fantastic. Reid’s also incredibly charming and intelligent in person. I could listen to her talk for hours.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I didn’t encounter Toni Cade Bambara’s work until probably three years ago, after I’d been working as a writer for quite a long time. Hers isn’t a name that comes up often enough in the American canon, which is mostly a dumpster fire, anyway, when it comes to recognition of value, at least as far as I’m concerned.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

The financial obligations of family: housing, healthcare, daycare, food, education—especially college savings. All the boring stuff. None of those is insignificant, though. If I only had responsibility for myself, I’d probably live in a van down by the river and write my ass off, at least after my first advance. But I don’t know if that would necessarily be a better life.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

My agent, Duvall Osteen, has always encouraged me to take care of myself first. I try to remember that, especially as a debut author; I’m typically in a state of such humility and gratitude that I overextend myself.

8. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I was recently reading an article in National Geographic about how the 1994 genocide in Rwanda resulted in a massive political reorganization of the country. A mandate of 30 percent parliamentary representation for women has led to huge changes in both laws and, to a lesser extent, norms. Rwandan parliament is now at 61 percent female—twice the mandate—with similar figures in other major institutions. Discriminatory laws of land and business ownership and gender-based violence have been eliminated. A new generation of women are reimagining their roles in society and being supported in that imagination. I’m still new to the publishing industry, so I don’t know exactly who’s in charge; but whoever is needs to deliberately retain, cultivate, and promote historically marginalized people—of color, gender, and every other category—into positions of significant, durable power. It’s the only way to achieve lasting equity. The art would be better for it.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

Danny Vazquez and Sean MacDonald, my editorial team at MCD/FSG. They’ve been excellent and frank in highlighting the weaknesses in my writing, without being overly prescriptive. At the same time, they’ve brought their own ideas to the work—things I never would have considered on my own—that have vastly improved this current novel.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I’ve been terrible at everything I’ve ever wanted to be good at—dating, tying my shoelaces, athletics, writing, driving, math, drawing, fashion, parenting—the first time I tried it. But years ago, my father, who’s a musician and public school teacher, told me about how much better his music had gotten when he’d just made it a point to commit to doing it—with focus and intention—on a daily basis. Even when it’s terrible. Especially when it’s terrible. Intentional, focused practice: That’s it. Maybe some people are phenomenal enough to not need it, but for me there’s no shortcut. Not for anything.