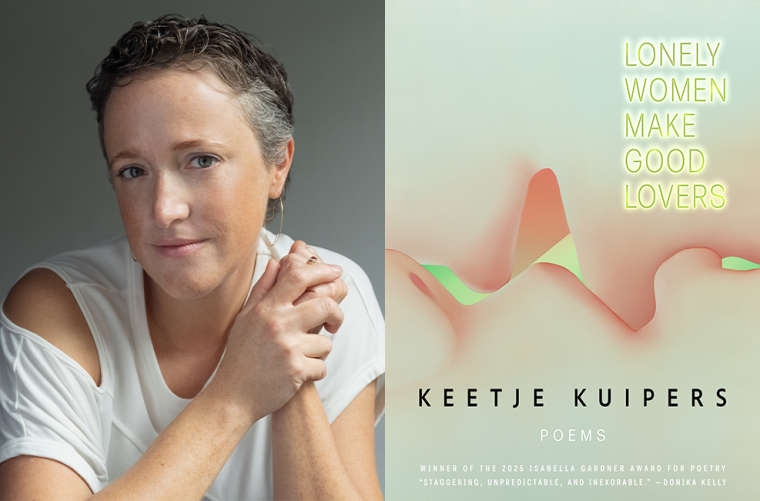

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Keetje Kuipers, whose poetry collection Lonely Women Make Good Lovers is out today from BOA Editions. These daring love poems—queer, complicated, and almost always compromised—explore humility, tenderness, and distance. Kuipers writes that love is a question “defined not by what we / cannot know of the world but what we cannot know of ourselves.” This collection explores the negative space of knowledge and includes lyric poems that interrogate the intimacy of marriage, the fetishization of freedom, and the terror of desire. Donika Kelly calls Lonely Women Make Good Lovers “a staggering, unpredictable, and inexorable collection,” adding, “these poems are nimble and vulnerable, mapping a return to the self, a return to longing, a return to the archive of what the body remembers.” Keetje Kuipers is the author of four books of poetry from BOA Editions, and the editor in chief of Poetry Northwest. Her first book, Beautiful in the Mouth, won the A. Poulin, Jr. Poetry Prize. Keetje’s poetry and prose have appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Poetry, American Poetry Review, and over a hundred other publications. She was a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, a Bread Loaf Fellow, the Margery Davis Boyden Wilderness Writing Resident, a former board member and vice president of the National Book Critics Circle, and is the recipient of a 2025 NEA fellowship. She lives in Montana with her wife and children.

Keetje Kuipers, author of Lonely Women Make Good Lovers. (Credit: Beowulf Sheehan)

1. How long did it take you to write Lonely Women Make Good Lovers?

The earliest poems I wrote for the book began to take shape in late 2018 and early 2019, just around the time my previous book, All Its Charms, was entering the world. There are always a few poems from the preceding book that feel like a bridge to the next one, and deciding where to make that cut-off—which poems belong to the last project and which poems belong to the next one—is impossible to see in the moment. But it’s something I actually like: the permeability of the projects, the way their edges blur, the idea that you can’t get to one without first having the other. One of the last poems to make its way into the manuscript for All Its Charms was a no-holds-barred love poem for my wife. I didn’t realize at the time that that poem was just the beginning of writing into my long and complicated love for her, something I got to do more of in Lonely Women Make Good Lovers. All of which is to say, it took me about five or six years to write the book.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I wanted to get back to a wildness that I felt like my work had been missing for a while. When I started writing the poems for my very first book, Beautiful in the Mouth, I didn’t have a lot of rules for myself on the page. Of course, I revised diligently and took the crafting of each poem seriously (I mean, I was in graduate school, so I was probably taking my work a little too seriously at that point!). Still, there was play and, again, wildness at work in those early poems. I had a kind of freedom then that I think is harder to recapture after you’ve published a book and started to (for better or for worse) regard your work as something that lives in the wider world. Looking back at the two books that came after that first one, it’s clear to me now that I became somewhat obsessed with polishing each subsequent poem to a perfect shine. Those poems lost their rough edges, which means that they lost the places where I—and a reader—might become uncomfortable or unsettled. I’m a firm believer these days in discomfort on the page, whether it’s sonic, tonal, metaphorical, or imagistic. Poems sometimes need places where things rub up against each other and make a rough sound. That’s the sound of ache, of real feeling, even of inexpressibility.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write almost exclusively when I’m on residencies. Or in the twenty minutes right before my writing group is about to meet and I need to come up with something to share with them. With my work teaching, mentoring, directing a reading series, and editing Poetry Northwest, literary service could easily take up all twenty-four of the measly hours of childcare I get each week. But I also use that time to administer to the human bonds of my life on the ground—making time to cultivate relationships with my parents and my best friend, to renew the bond I have with my own body and the natural world, and to reconnect with my wider community by volunteering at the local food bank. The poems are always going to be there—they are always going to push their way through the noise and make themselves known to me—if I can do the harder work of remembering what matters off the page. Twice a year when I’m at a residency for a couple of weeks, I pull out the folder of scraps of language I’ve jotted on notebook paper and disposable napkins and find that I’ve been doing the work steadily in stolen moments between living fully. There’s a lot to work with there, and I work with it very hard for fourteen days at a time.

4. What are you reading right now?

After serving on the National Book Critics Circle for three years—where, as a board member, I read hundreds of books in each new publication cycle across multiple genres—I’m gratified to have returned to reading whatever I want rather than whatever’s just hit the shelves. I’m slowly reading Virginia Woolf’s diaries, one page each morning with my cup of tea after my family has emptied out of the house. I read Anne Truitt’s Daybook (Pantheon Books, 1982) in a similar way and find that reading the diary of another writer or artist for just a few moments each day does wonders for clarifying my own thinking about creating and making work in the world. I’m also reading Anuk Arudpragasam’s A Passage North (Hogarth, 2021), which reminds me (in the best kind of way) of V. S. Naipaul’s The Enigma of Arrival (Knopf, 1987), which I read decades ago while backpacking around Spain by myself. Both novels make use of elements of autofiction, are philosophical in nature (I adore the lack of dialogue), and feel rooted in questions of relational perception. That kind of writing is a balm for my harried contemporary gerbil brain that is used to jumping from e-mail to app and back again. I long to find more deep, slow thinking when I open a book, as it’s something that seems hard to find almost anywhere else these days.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Rather than naming one single author, I’d like to consider the ways that our reading habits—as a nation—are still directed almost entirely by the publishers, agents, and critics located on the East Coast. In the age of #bookstagram and Zoom, it seems unlikely that this would remain true, but it is. I think regional writers deserve more recognition. I think that authors writing out of a precise place—wholeheartedly, with a sense of its complicated history and its many unique peoples, as opposed to a novel set in, say, the mountain West that plays to a mid-Atlantic reader’s preconceived notions of what such a place might be like—deserve a larger readership. I’m delighted by the tremendous number of translated books we are currently seeing come out from American publishers, and I love being a reader of global literature. But we happen to live in a vast country where we hardly know one another, hardly understand one another’s lives. What is it like to grow up as a child of immigrants in Seattle? Or to join the long tradition of river guiding on the Colorado? That kind of literature—coming out from smaller presses, winning regional bookseller’s awards—isn’t, for the most part, reaching a lot of readers beyond state and regional borders. And the truth is that we have a lot to learn about ourselves that we can only acquire through the wisdom of someone else’s hyperlocal gaze.

6. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I organized this collection during a two-week residency at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. My dear friend Rachel Edelman had advised me to create a set of index cards, each with the name of a poem and that poem’s themes, images, ideas, and first and last lines written on it. I set them all out on the studio floor and started moving them around, making sure I didn’t have two poems next to each other that, for instance, were both an address but to entirely different people. I tried to space out the poems full of animals or the ones with enjambed titles. But mostly, I tried to construct a narrative. Any book of poems—even the most lyric or abstract collection of poems—will tell a story once those poems are put into an order. I realized that this book wanted to tell a love story, one that, though complicated, is ultimately very happy. Once I had the beginnings of a workable order, I printed the poems out and tacked them to the wall in the order. For the next two weeks, I alternately moved them around, line-edited them, and cried. It was utterly painful at times to find a way to include each of them in the book. Some didn’t make the cut—not because I didn’t think they were good enough, but because they changed the story of the book in a way that I couldn’t make peace with.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

When I signed the contract for this book with BOA—the press that has published all three of my previous collections—my editor, Peter Conners, exuberantly wrote in his e-mail that the poems were “classic Kuipers!” I knew immediately what he meant: The poems are a return to the eros that was so important to my first collection, and they are a re-embracing of the narrative instincts I’d sometimes tried to shrug off in other books. The poems aren’t trying to be written in anyone else’s voice, only my own. It felt like a relief for one of my oldest readers to see my poems for themselves and to appreciate them in their, well, Keetje-ness. His words also helped me to believe in the book as I went through the torturous revision process with both the individual pieces and the manuscript as a whole. Even in my most intense moments of doubt about this book, I was buoyed by his faith in the poems as being—if nothing else—deeply and truly of me.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Lonely Women Make Good Lovers, what would you say?

As small as you feel right now—as tiny and insignificant and inconsequential as your life seems to you at this moment—you are about to go on an emotional journey of even greater smallness. It’s going to involve a kind of work in humility that you haven’t done a lot of. It is going to challenge how you see yourself in relation to those you love and in relation to those you don’t even know. And on the other side of that journey will be some poems.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Lonely Women Make Good Lovers?

I could not have written this book without the hard work of therapy. It sounds like such a cliché, but it’s true. There are so few places left in our contemporary Western culture where we have the opportunity to be directly taught about compassion for ourselves and for others. We’re supposed to learn those sorts of lifelong lessons in ego-diminishment through observation, literature, and, if we’re lucky, our parents. But that feels like a very under-cultivated process of osmosis in our current society. What I learned from my therapist about humility and connection filled in some important gaps, and not only directly influenced the way I try to live my life, but also profoundly changed the creative work that I make.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

“You don’t need those last three lines.” And honestly, you really never do.