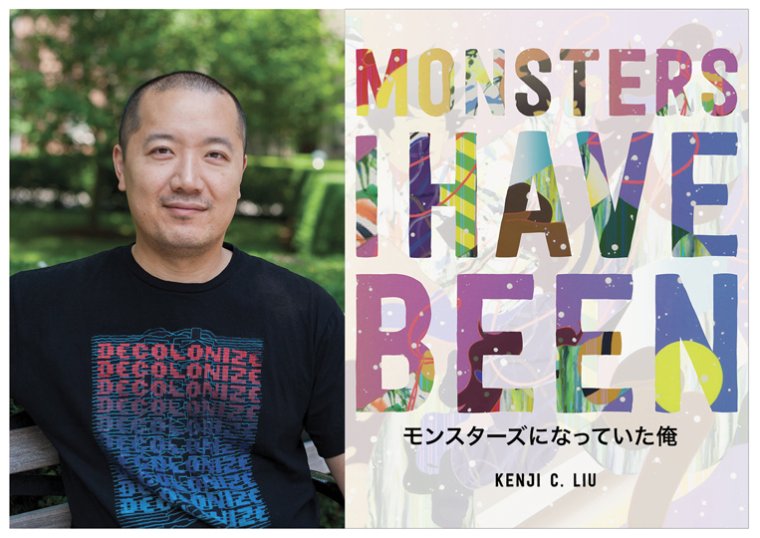

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kenji C. Liu, whose second poetry collection, Monsters I Have Been, is out today from Alice James Books. Using an invented method he calls “frankenpo” (or Frankenstein poetry), Liu takes an existing text and remixes it, resurrecting older work to create new poetry that investigates the intersections between toxic masculinity, violence, and marginalization. A book that Douglas Kearney calls “sharp, protean, dextrous, and discontent,” Liu’s collection “shows where the bodies have been buried, and that many won’t stay dead. No doubt, this book is alive as hell.” Kenji C. Liu is the author of a previous poetry collection, Map of an Onion (Inlandia Institute, 2016), winner of the 2015 Hillary Gravendyk Poetry Prize, and two chapbooks. His poems have appeared in American Poetry Review, Apogee, Barrow Street, the Progressive, the Rumpus, and other publications. A Kundiman fellow and an alumnus of the VONA/Voices workhop, the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley, and the Djerassi Resident Artist Program, he lives in Los Angeles.

Kenji C. Liu, author of Monsters I Have Been. (Credit: Margarita Corporan)

1. How long did it take you to write Monsters I Have Been?

It took about three years, coming on the heels of my first collection. I was trying to figure out what to do next, and received some great advice from Jaswinder Bolina while at the Kundiman retreat. He suggested I pick a line or idea from my first collection that still felt juicy and go all the way down the rabbit hole with it. I did, and Monsters I Have Been is a direct result.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Since the book looks at various types of masculinities, I had to seriously reflect on how to write responsibly about gender. Toxic and conventional masculinities were easier, considering that there are always fresh examples in the news ad nauseam, though I did also try to give them some complexity without excusing away their violence. Unconventional masculinities were more challenging because I didn’t want to replicate dominant forms of representational violence. So I decided to approach these via some of the ways I’ve experienced being racially gendered, misgendered, and sexualized as an Asian American man.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

What’s kept me going is a semi-underground, e-mail–based writing accountability group where you sign up to write every day for a month. Recently I haven’t had time for it, but for many years I joined in for months at a time. When I participate, I write everywhere and anytime, often just a sentence or line per day. I might be at work, in transit, or even stranger places. After doing this consistently for years, writing feels like a habit, something you do every day like brushing your teeth. Writing becomes less “special,” which I consider to be a good thing.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

There wasn’t anything in particular about the publication process, but the DIY digital marketing campaign I undertook to promote the book ahead of publication created some unexpected results. Drawing on my experience in design and marketing, I decided to focus on an Instagram account (@monstersihavebeen) dedicated solely to the themes of the book, which cross-posted to Facebook and Twitter. I found this created a lot of advance interest, and really helped me gauge the book’s audience ahead of time.

5. What are you reading right now?

The Inheritance of Haunting by Heidi Andrea Restrepo Rhodes, 2018 winner of the Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize; I Even Regret Night, poems of Lalbihari Sharma, an indentured Indian servant in the Caribbean, translated by Rajiv Mohabir; American Sutra, on religious freedom and Japanese American Buddhists imprisoned in U.S. concentration camps during World War II, by Duncan Ryuken Williams; and Oculus by Sally Wen Mao.

6. Which authors, in your opinion, deserve wider recognition?

Vickie Vértiz, Muriel Leung, Sesshu Foster, Angela Peñaredondo, Mia Ayumi Malhotra.

7. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

I experience my corner of the poetry community as very generous and caring, but I have many issues with professionalizing poetry as a career with certain prizes and residencies you “have to” achieve—it can make people greedy, competitive, and encourage a perception of the world based on lack. I think the poetry community works better when it is cooperative and generous. Poetry shouldn’t be just another capitalist product.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Money and time.

9. What trait do you most value in an editor?

I need to sense that they understand what my project is trying to do at a fundamental level. Alice James Books seems to have had that understanding immediately, which I’m grateful for because Monsters I Have Been might take some time for the reader’s brain to adjust to if you have conventional expectations of poetry. If an editor, press, reviewer, or anyone else doesn’t seem to understand the project, it’s clearly not a good fit.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

What I actually think of is a writing prompt I received from the poet Suheir Hammad many years ago. She asked us to write about a traumatic experience, and also to find something in the environment of the memory that was beautiful. For me, I think this has translated into ongoing writing advice—to look for beauty and grace even in the challenging material, whenever possible.