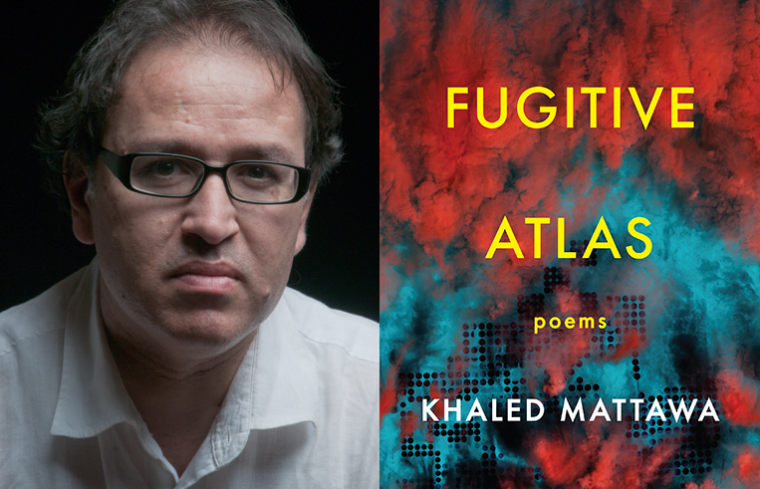

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Khaled Mattawa, whose fifth poetry collection, Fugitive Atlas, is out today from Graywolf Press. Early in Fugitive Atlas, Mattawa poses the question, “How to stop thinking of bodies / as worth extinction, worth eating or enslaving”? Examining both ancient cruelties and contemporary social, political, and environmental crises, Mattawa exposes how humans have become desensitized to suffering, and searches for a path forward. Employing inventive and various forms—one poem, for instance, adopts the structure of an index to break down the language of military occupation—Mattawa reckons with what it means to be human in a troubled and troubling age. “These are poems of exceptionally real human and political consequence, filled with news that the news does not speak,” writes Alberto Riós. “Khaled Mattawa’s Fugitive Atlas is a work of uncommon, poignant character, of resonance and depth.” Khaled Mattawa is the author of four previous collections of poetry, most recently Tocqueville, and the translator of nine books of contemporary Arabic poetry. He received an MA and an MFA from Indiana University, and earned his PhD from Duke University.

Khaled Mattawa, author of Fugitive Atlas. (Credit: Khairy Shaban)

1. How long did it take you to write Fugitive Atlas?

Nine years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Settling on the core themes of the book and how best to represent them. For the first five years I did not think I had a book. But once the central sequence of poems emerged, it was a matter of creating a mural where all the parts fit to tell a kind of story.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write mostly at home. I begin with an idea and set it aside, but depending on how I’m drawn to it, I might or might not go back to finish the poem. I think that’s what happens. But in reality, writing seems like a dreamy activity to me. Fugitive Atlas has a sequence of haibun that I no longer recall how and when I wrote. The process must have involved being ensconced at my desk for several days. I realize that sounds torturous, but given that I have no memory of it, it was very likely an ecstatic experience. I don’t go on residencies because my schedule is never that open, but a ten-day residency at the University of Arizona Poetry Center was a very productive time for me. But there too I don’t remember which poems were written during that residency. Written in the sphere of the imagination, poems perhaps seek to be their own beings, not attached to us or to the time in which we wrote them.

4. What are you reading right now?

The Devil’s Pool by George Sand.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

There are so many.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Time and everything else. I am engaged in so many extracurricular activities—editing a journal, translation, arts activism, administration—that keep me from writing. But the truth is I need them to stay away from writing, or to refuel my mind for writing. After finishing a book, even if I have a project in mind, trying to write can be demoralizing. The new book project is insisting that it be new, that you renew yourself, which means you have to teach yourself how to write again. I don’t know if that’s an impediment. Maybe it’s just the enduring challenge of the process.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

My editor said, “This is your best work,” which made me feel very good about the book and about my career as a poet.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Fugitive Atlas, what would you say?

I hear you’re working on a series of poems about Greek myths told from a postcolonial perspective. Good luck with that!

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

The editor I’m working with. I sought help from several friends with Fugitive Atlas, which I don’t do normally as I think it’s such a big imposition on one’s time. But I did this time and received excellent feedback. However, a book gets built and rebuilt in the editorial process, and for that the editor you’re working with is important. I very much enjoyed working with Jeff Shotts at Graywolf who read and reread the book several times.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Don’t ever find your voice.