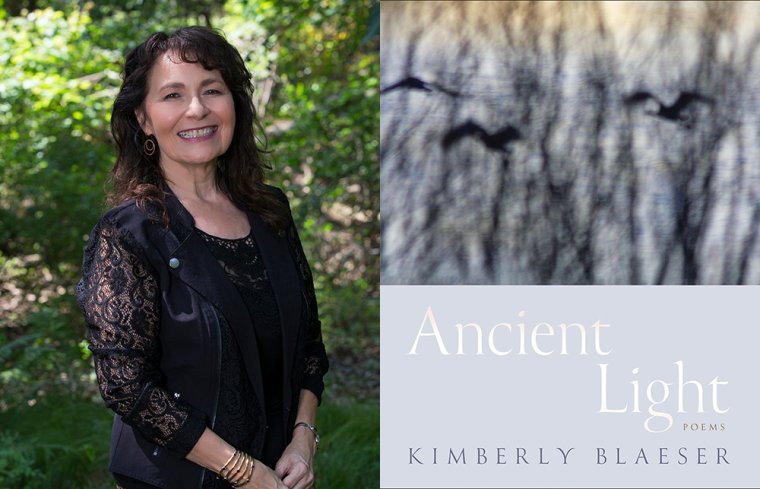

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kimberly Blaeser, whose new poetry collection, Ancient Light, is out today from the University of Arizona Press. These haunting poems illuminate the nature of loss as it is experienced on multiple levels—personal, familial, cultural, historical—and the ways in which life manages to persist in spite of it. Mixing English and Anishinaabemowin, lyrics and visual poetry, the book also explores the paradoxical power of language. It can be “a salve,” as Blaeser puts it in the book’s opening poem, “Akawe, a prelude,” enabling people to name the dead or communicate pain. But it can also serve as tool of control, regulating the ways in which people express themselves. This is particularly true in the United States, where English was forced upon Indigenous populations. Ancient Light directly confronts the nation’s violent colonial legacy, asking readers to understand “our continent, draw 1491” and how it was “reshape[d] by discovery, displacement,” as she writes in “Poem on Disappearance.” Yet the book retains hope for a more peaceful and open-hearted future, “an abundance we make / of the broken—when burst becomes seed,” Blaeser writes in “Mazínígwaaso: Florets.” The former poet laureate of Wisconsin and the founding director of In-Na-Po, Indigenous Nations Poets, Kimberly Blaeser is the author of several poetry collections, including Copper Yearning (Holy Cow! Press, 2019). A recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas, Blaeser is an Anishinaabe activist and environmentalist enrolled at White Earth Nation. She is a professor emerita at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee and a faculty member of the Institute of American Indian Arts’ MFA program in creative writing.

Kimberly Blaeser, author of Ancient Light. (Credit: John Fisher)

1. How long did it take you to write Ancient Light?

I wrote some of the poems in Ancient Light as early as 2016 and had two books that came out since then—Copper Yearning in 2019 and Résister en Dansant in 2020—but the poems didn’t belong to those volumes. So it would be fair to say I have been working on the poems for seven years. The book was a finalist or semifinalist for a couple competitions, so I knew it was close. The experience of the pandemic and awareness of racial injustice heightened by the murder of George Floyd led me to sharpen the premise and movements of the book. The possibility of and need for healing, different pathways, and another way to be in the world grew more urgent both in our physical spaces and in the book as it moved toward its final version.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Ordering the poems to support the movements of the collection proved the most challenging. Generous early readers and the reviewers for the press all offered advice on reordering. Each idea seemed valuable, but none agreed with the others! As an exercise, I created section titles. This illuminated the bones of the collection. It led to some rearrangement, but I also added some poems and subtracted others. Ultimately I chose to remove the section titles, not wanting to impose a single map on the reader or even on the poems—since I hope the poems will manifest intuitive connections and prove themselves wiser than their transcriber. I did add a poetic prelude, which I view as a map of sorts.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I often write in kayaks, on the ledge rock at our cabin in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW), in a hammock beneath an ancient oak on our property in Wisconsin, on decks here and there, and also at my desk in my home library. In recent years, I have been blessed to travel to writing residencies—most recently in Italy, where I wrote in the foothills of the Alps and in the mountains as well as in beautiful gardens overlooking Lake Como. All that to say, I often write outdoors, by hand, when it is daylight, with the “where” of my writing often determining the content. I frequently begin my day with coffee, my journal, my camera, and a book, each of which contributes to morning writing. On mornings at BWCAW, I often paddle out with coffee in a thermos to a favorite bay and settle in there. I try to work every day, even if I only produce a few notes or the skeleton of an idea. I have drafted many poems first in my journal. When I have longer writing sessions, I mine those jottings or drafts. This I do frequently at my desk at night when the house is quiet.

4. What are you reading right now?

I have just begun Brendan Shay Basham’s novel Swim Home to the Vanished. Brendan is both a poet and a prose writer, so his fiction is lush and suggestive like poetry as well as narratively powerful. I am also reading, partly rereading, a collection of poetry by Algerian writer Samira Negrouche, The Olive Trees’ Jazz. Samira writes mainly in French, and this collection is translated by Marilyn Hacker. Even though we live continents apart, I relate to Samira’s embodiment of the tentacles and repercussions of colonization, her understanding of the indelible mark violence leaves on people as well as places, and I appreciate the spiritual allusiveness of the poems.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

After its prelude “map,” Ancient Light begins with poems depicting the conditions and consequences of colonization—a possessive mindset that leads to exploitation of resources, of Indigenous bodies, of language itself. It moves then to suggest a turn toward potential sources of healing. Poems embody specific instances of relatedness or of lives illuminated by “ancient light” in the many ways this may be cast or manifested: modes of being embedded in Anishinaabe language for instance, traditional Indigenous knowledge, or patterns of the land itself. Certain poems or particular scenes complicate the human factor, as the book includes both grief and many kinds of loss—some of it personal. Finally the collection gestures toward alternate understandings, ways of measuring, and a different scale of value. The spilled light of tradition remains viable as pathway and tool of survivance—“an abundance we make / of the broken—when burst becomes seed,” as one poem claims.

6. How did you arrive at the title Ancient Light for this collection?

The title actually arose from a particular encounter, which later become a visual image, now a “picto-poem” in the book with that phrase in the title, “Waaban: ancient light enters.” While canoeing with my son, I made photos of a Great Blue Heron. We came under the spell of the immense bird as it lifted off or landed with great pomp, stalked and swallowed whole yellow-bellied fish, spread its wings and stretched its legs into forever as it flew backlit by sunset sky. When I later looked at the photos, and they seemed anemic compared to the experience itself, I realized we never only see what we see—we always see what we bring to the moment. I brought my understanding of the Anishinaabe Crane Clan and stories of bineshiinyag, or bird relatives, as messengers between Earth and sky. I ultimately created the picto-poem, in which woodland beadwork symbolically becomes the sky and pieces of poetic language wrap themselves around that other way of knowing. I began to think about the ways all our experience is suffused with these ancient understandings. Because visually in that moment the spilling light helped illuminate the internal and external experience, I thought about how long and far light sometimes travels before it reaches us and we apprehend it. From that ruminating, the title arrived, and I understood it as representative of more than that single experience.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Ancient Light?

Although I have often written ekphrastic work, have been experimenting with the layers of text and image I call picto-poems, and work in concrete as well as lyric poetry, I was surprised at how readily these various creative approaches came together. I found they “play well” with one another. I have also been writing and continue to write slight poems, all entitled “The Way We Love Something Small.” I thought of them as a series of poems; but in assembling Ancient Light, I realized they are an aesthetic as much as a form.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Ancient Light, what would you say?

Mainly I would say, “Don’t hurry.” I really need to repeat that as a mantra. When I feel inspired by an idea or project, I tend to expect the path to be straightforward. It seldom is and certainly wasn’t in this instance.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I am Anishinaabe, and I used quite a bit of my Indigenous language, Anishinaabemowin, in Ancient Light. Although I spent early years with grandparents for whom this was a first language, I am still a language learner. I once asked in a poem, “How can you conjugate after forty?” But because I understand the importance of the work of what I call #LanguageBack for the nonprofit I founded (Indigenous Nations Poets), I put in effort to move from “baby” Ojibwe. I incorporated the appropriate prefixes and suffixes that signal relationships, and I worked to carry the embedded language teachings into the poems (even when Anishinaabemowin might not be used itself).

Because, as I mentioned earlier, I often have both camera and pencil on nature adventures, I also upped the ante on my photo work. Photos often help inspire the poems and vice versa. Then I work through the process of bringing them together in diptychs or picto-poems. Even though only a handful of these ultimately made it into the collection, figuring out how to wed the visual and verbal involved my learning some technological razzle-dazzle.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

I sometimes cling too closely to “sense.” When lamenting this in conversation with one of my writing friends, he suggested I trust my intuition and trust my reader to follow the leaps of that intuition. I remind myself of this advice often.