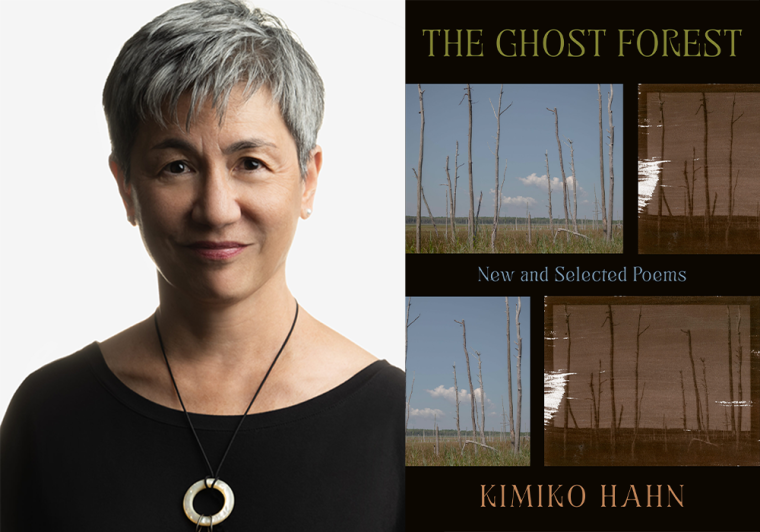

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kimiko Hahn, whose collection The Ghost Forest: New and Selected Poems is out today from W. W. Norton. The book features forty-three new formally inventive poems as well as selections from Hahn’s ten previous volumes. The Ghost Forest offers a contemplative and haunting narrative of a writer’s artistic journey through craft and form while illuminating personal themes influenced by her Japanese American heritage. Hahn explores science, nature, and the experience of contemporary womanhood while reinventing Japanese forms such as the zuihitsu and tanka and experimenting with traditional Western form such as the villanelle, sestina, and glosa. Nicole Sealey called the book an “evocative braided autobiography in poetry that welcomes miscellany and disorder...and reveals a mind as vast as the terrain it traverses.” Kimiko Hahn has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, the PEN/Voelcker Award, the Shelley Memorial Award, and fellowships from the National Endowment of the Arts and the New York Foundation for the Arts. Hahn has taught in graduate programs at the University of Houston and New York University and is a distinguished professor in the MFA Program in Creative Writing and Literary Translation at Queens College, the City University of New York. She has also taught for literary organizations such as the Fine Arts Work Center, Cave Canem, and Kundiman.

Kimiko Hahn, author of The Ghost Forest: New and Selected Poems. (Credit: Beowulf Sheehan)

1. How long did it take you to write The Ghost Forest?

The Ghost Forest is a new and selected collection, so I could say it’s taken all my life. I hope the title suggests a kind of haunted dimension that extends into my very early years. The phrase comes from a New York Times article I read on that phenomenon: When ocean levels rise due to climate change, sea water seeps onto the coasts and into freshwater marshes, killing off the plants. Dead trees remain; hence a dead forest. I was prompted to write two pieces: a sestina and an erasure.

The new poems took about five years or so. During that time, I was increasingly drawn to form—this was relatively new for me, having been a free-verse hippy in my younger days, typical of my generation. I was captivated by villanelle, the rocking of the repeated lines. Also, the sestina’s repetition although it took me decades, on and off, to finally find a discursive flow that allowed for more than exercise. A grad student introduced our workshop to the triolet. And during the pandemic, I “discovered” the glosa. I was especially keen on giving homage to past writers in the way that the golden shovel offers. The glosa opens with lines from another poet’s poem, setting a pattern in motion. Speaking of golden shovels, for mine, I used haiku by Richard Wright and Japanese ones translated by Hiroaki Sato (with his generous permission). Once I’d written in these forms, I often used them as drafts, so in the end there is only the ghost of, say, a sestina. I like the seductive quality of not quite knowing what is going on, that is, why a word keeps repeating but not in a set pattern.

I showed the early manuscript to several poets for feedback, and Jan Heller Levi made two invaluable suggestions: The first, to turn the whole manuscript into a zuihitsu (a Japanese genre that I’ve explored over the years). So, I created a kind of thread that runs throughout. In it I comment on writing and teachers and influences. I play with words—a palm of psalms, a jar of voltas, a grip of blazons. The collection moves from the newest work back in time to my first book, Air Pocket, back to that young woman. I made some slight revisions, and, in a way, I felt I was mentoring my younger self. The book designer placed the thread on gray pages—which I think feels a bit ghostly. Seeing the new draft, Jan agreed that the collection felt whole, rather than strictly sectioned. Early on, she also questioned whether the title really spoke to the collection as a whole. With the thread, the whole became haunted by the sense of the ghost forest.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Some of my early poems are quite lengthy. I included somewhat excerpted versions of “The Hemisphere: Kuchuk Hanem,” “Resistance: A Poem on Ikat,” and “The Izu Dancer.” I think they are actually stronger for the trimming. I would have liked to include more, especially from Volatile (1999)—but there was only so much space. I also decided not to include more than a couple zuihitsu.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I have fresh energy in the morning after breakfast. I am less distracted by the day (although e-mails are a struggle). I used to write in coffee shops on yellow legal pads—the Hungarian Pastry Shop on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, The Rising Cafe in Park Slope. That was when my children were small and all the domestic stuff (laundry!) was a distraction. Nowadays I write at home on my laptop. How often? pretty much every day, even if it’s dictating a few lines into my mobile. That said, The Ghost Forest took so much work that I feel the wind was knocked out of me. I am writing this while traveling in Japan and, once home, I might return to the coffee shop if only to shake up my routine.

4. What are you reading right now?

I was asked to say a few words at an Archipelago Books fete (they publish books in translation) so, to prepare, I asked for about a dozen poetry collections. My favorites: The Brush (2024) by Eliana Hernández-Pachón (translated from Spanish by Robin Myers) and Allegria (2020) by Giuseppe Ungaretti (translated from Italian by Geoffrey Brock). This summer I reread The Columbia Anthology of Japanese Essays (Columbia University Press, 2014), edited and translated by Steven Carter. Then I read the Regeneration Trilogy (Viking Press, 1991–1995), by Pat Barker. I couldn’t stop reading it and was sorry when I completed the three. I also proofread my husband Harold Schechter’s true crime books! While traveling in Japan, I’ve been reading Earthlings (Grove Press, 2020) by Sayaka Murata.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

More than any one writer, I think works in translation are given short shrift.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Myself.

7. What is one thing that your editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Jill Bialosky has been my editor for many years and for many of the collections she has given invaluable suggestions regarding the structure of the book. It’s funny, a few times I used advice from one book for the next, but, no surprise, she then offered a different idea. Of course! Each collection called for a different structure! I keep learning from her and now I don’t try to merely replicate a structure. Also, I use what I’ve learned from her when advising my graduate student theses.

For The Ghost Forest, as I said, I added the ruminative thread. This idea was similar to the advice she gave for both Mosquito and Ant (Norton, 2020), and Toxic Flora (Norton, 2011). For the latter she suggested I take out the several zuihitsu but choose one and flip paragraphs from it throughout. I chose the piece on sexual cannibalism—and, in a sense, the collection is an act of sexual cannibalism.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Ghost Forest, what would you say?

Over the years I have had various therapists and feel that I have been speaking with my former self. Urging her to continue to let go of shame and take further risks. Aside from giving myself permission, I would probably urge her to hold on to the manuscript a bit longer and revise more. But, without the benefit of graduate-level craft classes, I might not have been prepared to go any farther than I did. The real issue is—now what?

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of The Ghost Forest?

Objects have taken center stage, beyond Williams Carlos Williams’s “no idea but in things.” And I love the cover of Foreign Bodies (Norton, 2020): objects that Dr. Chevalier Quixote Jackson removed from children. I was interested in including more of these kinds of objects—things I might have swallowed. So I began taking snapshots of domestic items (safety pins, buttons) and moved to personal ones (Girl Scout pins, Great Grandfather’s anniversary pin). These photos became a visual narrative line moving from the general to the personal. So there are several strands: the poems, the thread, and the photos.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I was in an undergraduate workshop with Marvin Bell at the University of Iowa. He said something to the effect of: “You can’t fool the unconscious.” And it’s true—you can go with intention, or you can explore where the poem leads you. Where your unconscious leads you. To quote Frost, “And this has made all the difference.”