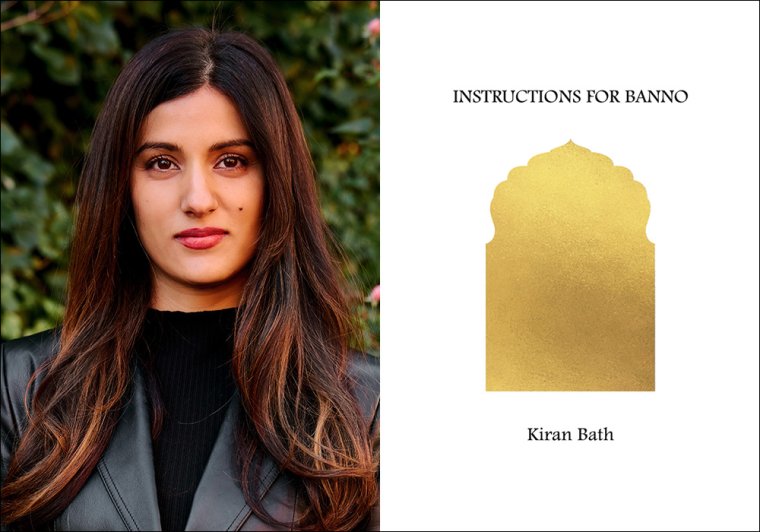

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kiran Bath, whose debut poetry collection, Instructions for Banno, is out this week from Kelsey Street Press. In this surprising collection of prose poems and experimental verse, Bath offers a compendium of lyrical advice for girls and women entering marriage in South Asia. Many of the poems are written in the voice of an individual banno, or bride, who considers her particular experience within traditional South Asian culture. At the center of that experience is the figure of the patriarch—who begins as an object of desire in the lead-up to marriage, then becomes one of reverence and submission after the nuptials have been secured. “Picture me: Little dowry, rich ovaries. He could have been my father,” says one banno named Persini. “Don’t pity me. I was the papaya spring.” Amid these banno-voices the author “interrupts,” directly questioning and complicating the words spoken by each banno while also narrating her own experience as a woman once removed from banno culture. In “The Poet interrupts: How to fuck anew,” for example, the speaker considers her own sexual experiences; in “The Poet interrupts: Mind cast of the bride,” the speaker engages in a meditation on “the psyche of Banno,” wondering “would it be circular or linear?” Poet Tarfia Faizullah praises Instructions for Banno: “These poems are at turns lush, defiant, modern and ancient, a lively and loving record reminding us that life is designed as much as it is inherited.” Kiran Bath has received fellowships and support from Poets House, the Vermont Studio Center, and Brooklyn Poets. A Kundiman fellow and an alumnus of the Tin House Workshop, her writing has appeared in the Adroit Journal, the Brooklyn Rail, Wildness, and elsewhere.

Kiran Bath, author of Instructions for Banno. (Credit: Elena Mudd)

1. How long did it take you to write Instructions for Banno?

The manuscript took just under two years. But I otherwise feel as if I’ve been writing this book all my life and will keep writing it. By that I mean that the book draws from personal and familial narratives that are ongoing and ever-evolving.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I think maintaining the emotional stamina for a book that was so deeply personal was definitely challenging. At various points I had to stop and return to the page when I had a stronger stomach for some of its more violent moments, or when I felt I simply wasn’t doing justice to the memory of the women the book is about.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I am a fussy eater and an even fussier writer. I am working on loosening up on both! I find that I write best in the early morning and in coffee shops—always. There’s something about a blank day and the smell and sound of fresh coffee being made, on repeat, that just puts me to work. Plus, being a full-time lawyer, I usually only have time in the earliest or latest hours, the latter being when I’m too depleted to muster any creative force. I should add that I’m a pretty moody creator too. I’ll go on strike for months at a time and wait to be connected to the project again to resume. When I’m active, I try to put in four to five early mornings a week.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m actually reading more fiction these days. I just finished All the Lovers in the Night by Mieko Kawakami; it was sad and strange and beautifully executed. I’ve just started the much-anticipated new story collection, Roman Stories, by Jhumpa Lahiri. Her character building, especially in the tight lapses of short stories, is incredible. I often reread my favorite authors and am jumping back into the Anaïs Nin diaries. There could not be a more dedicated and eloquent diarist.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

At first I thought about arranging the persona poems chronologically by each generation. I soon realized I didn’t want readers to be distracted by the speaker’s orientation in time. Rather I wanted the voices—modern, pre-partition, post-migration—to be comingled as I hoped it would emphasize the unanimity of the Banno ideal that is superimposed on them all, irrespective of time and place. I also wanted the sequence “The Poet Interrupts” to feel like a whole other plane of time-space-reality in the book—a “play within a play” if you will, where the Poet could comment on the experiences of the women and really wrestle with the questions that keep circling in the book in a way that interacts with the reader more directly.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

It really depends. If you have the resources and time to do it, why not? It offers a very structured and disciplined way to build your craft. But I can’t say I’d prescribe it because I don’t believe it’s necessary whatsoever to become an author. My greatest method of learning has been to read as widely as I can, as much as I can. Beyond that, as someone who did not do an MFA, I was fortunate enough to partake in various residencies, workshops, and fellowships, which together offered the richness and critical thinking that worked for me. I’d definitely encourage people to seek out and apply to whatever they can outside of the traditional academic format and see how that shapes their practice.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Instructions for Banno?

Probably the surrealism of being inside your book. It’s always stuck with me how Robin Coste Lewis described meeting the Sable Venus and traveling through time with her as she wrote the book Voyage of the Sable Venus and Other Poems. The deeper I got into the manuscript, the more new bannos kept popping up in my dreams, in my pages, in my daytime thoughts. There were a plurality of voices speaking to me all at once, and they were, quite frankly, a very noisy bunch to live with during the latter part of the writing journey.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Instructions for Banno, what would you say?

The book is already inside of you, and it will come out onto the page when you are both ready. Though knowing me, I doubt the past me would heed the advice.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

A lot of research went into the book. I went as far back as the ancient Sanskrit texts of the Kama Sutra and Sattasaī to understand the origins of misogyny in South Asia. I considered historical figures like Mumtaz Mahal (the Mughal Queen for whom the Taj Mahal was made) right through to Nirbhaya (the victim of the horrific 2012 Dehli gang rape and murder). My research also took me through the oral histories and recorded memories of the women in my own family’s lineage. I also went back to a lot of South Asian music and film to remind myself of the archetypes I grew up with.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

I always struggle with the superlative, so I’ll give my top three:

Don’t force it. The time between when you’ve lived the thing you want to write about and when you start writing about it can be a matter of months, years, or even decades.

Don’t worry about coming across as emulating any other author’s style, particularly the ones you admire. You’ll inevitably write in the style and substance of you.

Just tell the truth.