This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kwame Alexander, whose new book, Why Fathers Cry at Night: A Memoir in Love Poems, Recipes, Letters, and Remembrances, is out now from Little, Brown. In this mix of poetry, prose, and directions for cooking beloved dishes—such as “Turkey Legs With Noodles”—Alexander offers “snapshots of a man learning to love.” Written in the midst of mid-life losses—including the death of his mother and the end of his marriage—Alexander reflects on the journey that has led him to this moment. Considering his parents’ marriage and influence, his time studying with the poet Nikki Giovanni, falling in love, fatherhood, and building a writing life, Alexander gives readers a window into his evolving worldview and his own personal reckoning: “You wrote this book as a nudge to yourself,” he writes. “To be single? / To be by yourself. And remind yourself that being alone is not the same as being lonely.” Publishers Weekly praises Why Fathers Cry at Night: “This candid and courageous work finds poetry in places both ordinary and extraordinary. It’s a quiet triumph.” Kwame Alexander is a poet, educator, producer, and the best-selling author of more than three dozen books, including The Crossover (HMH Books for Young Readers, 2014), which won the 2015 Newbery award for children’s literature.

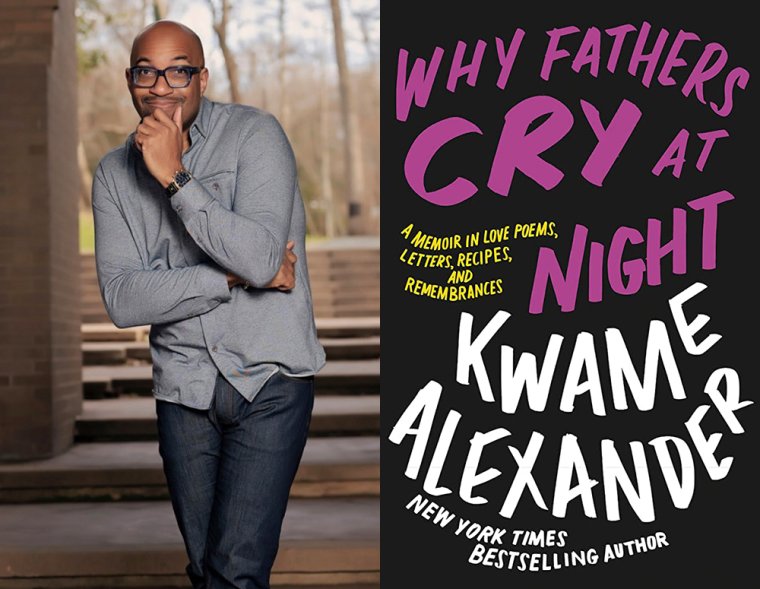

Kwame Alexander, author of Why Fathers Cry at Night: A Memoir in Love Poems, Recipes, Letters, and Remembrances. (Credit: Portia Wiggins)

1. How long did it take you to write Why Fathers Cry at Night?

I’ve really been thinking about the themes of the book, and writing occasionally, as a way to understand all the feelings I was dealing with since my mother passed on September 1, 2017. But I began the book in earnest probably in 2021.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Well, most certainly it was writing the last part of the book. I could write about my father, my marriages, my uncouplings, my daughters with a level of comfort, and therefore rhythm, that bailed on me when I began writing about my mother. I put it off, literally, until weeks before the book deadline. Her death was the thing that I had not thought about too much because it just hurt. So I waited, and it was indeed the hardest section to write. It was also the most enjoyable—the precious memories. In the end, they proved quite comforting.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

For this project, I woke up every day in my London penthouse and wrote from about 6:00 AM to 11:00 AM. And I would send some of the poems to friends, to family. I’d also go for walks in Regents Park or Hyde Park and think a lot, replay experiences and conversations from my life, listen to podcasts and audiobooks—of Neruda’s poems, memoirs, cookbooks—for inspiration.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m listening to Wild Game by my friend Adrienne Brodeur. I’ve just read more than a hundred poetry books as research for an anthology of contemporary Black poets that I’m editing. And next to my bedside for “light” reading is The Trees by Percival Everett.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

It’s always three people: my parents and Nikki Giovanni. It is these writers who have taught me most of what I know about storytelling. Pearl Cleage, Matthew McConaughey, and Pat Conroy have such uniquely powerful voices that I found their memoirs unputdownable and tremendous templates for how to tell my own story. In terms of Why Fathers Cry at Night, I found incredible inspiration and insight in conversation with several writer friends—Jacqueline Woodson, Jason Reynolds, Christine Platt, and Alice Cardini, to name a few.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Why Fathers Cry at Night?

That it became a memoir. It was supposed to be a collection of love poems—romantic and familial. My hope was that readers would find it interesting and that some of the poems might resonate. As I got further into writing it, my editor commented that the book read chronologically and that perhaps I should consider writing a few prose pieces to make the narrative more concrete. Then I added a few recipes and letters, and we both saw a memoir—albeit an unconventional one—developing. Then she asked for more prose pieces. I was expecting to allude to, hint at, speak in metaphor about my love life, not put all my business out into the world. Oh, my!

7. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

I was three years old, learning how to appreciate words. And basketball. There’s a story I tell in the book about my favorite book back then, so I won’t spoil it for you here. But I will share that my father would often take me to the playground near Columbia University, where he and my mother were in graduate school. He would shoot free-throws, and then he would give me the ball and tell me to do the same thing. Now, I’m three years old, so there’s no way my shot is going anywhere near the basket. The playground supervisor walks over with a big wrench and tells my dad that he will lower the goal so that I can make a basket. My father stops him and says, “No, he doesn’t know he can’t make it.” I ended up writing a whole book of “basketball rules” for life inspired by that moment. Never let anyone lower your goals. Always shoot for the sun, and eventually you will shine.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Why Fathers Cry at Night, what would you say?

Writing this book forced me to deal with, and face, some parts of my personality that haven’t served me. One was my inability to open up, share, be vulnerable with dear colleagues and friends who cared about me. There are friends who gave me sound input near the completion of the book—when I was ready to hear it—that I wished I would have had the courage to talk about and listen to earlier in the writing, because I think I would have been inspired, maybe even been more courageous, to go even deeper than I did. The good thing is, there can always be another book.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

As I mentioned, I did a lot of walking as a way to prewrite, reflect, and just give myself the time and space to think through some of the heavy topics I was writing about. I spent a great deal of time in the kitchen, making each of the recipes at least a dozen times to ensure that the meals tasted as good as I remembered.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

As I write in the book, frustrated after receiving a C-minus in Nikki Giovanni’s advanced poetry class in college, I scheduled an appointment with her during her office hours. She told me, “Kwame, I can teach you how to write poetry, but I cannot teach you how to be interesting.” While nineteen-year-old me thought those were pretty harsh words, it turns out that I have spent my entire writerly life walking around as an eager and engaged participant so I’d have something worth writing about.