This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Latif Askia Ba, whose poetry collection The Choreic Period is out today from Milkweed Editions. The collection explores disability, syntax, and rhythm, and radically reclaims movement and the body. Latif Askia Ba, a Senegalese American writer with cerebral palsy, integrates French, Spanish, Jamaican, Fulani, and Wolof into his lyric, reminding the Anglophone reader: “I am not here to accommodate you.” Percussive and syncopated, his poems honor the elements of our unique choreographies. CAConrad writes, “In brilliant flashes, the poems pull us into their innovation. A period. Takes the pause. If a period could be italicized, this is the poet who could do it,” adding, “I love every moment in every poem, I’m a huge fan.” Latif Askia Ba received his MFA in creative writing from Columbia University and was the print poetry editor for the Columbia Journal’s sixty-first issue. He is the author of The Machine Code of a Bleeding Moon (Stillhouse Press, 2022), and his work has appeared in Poetry and other publications.

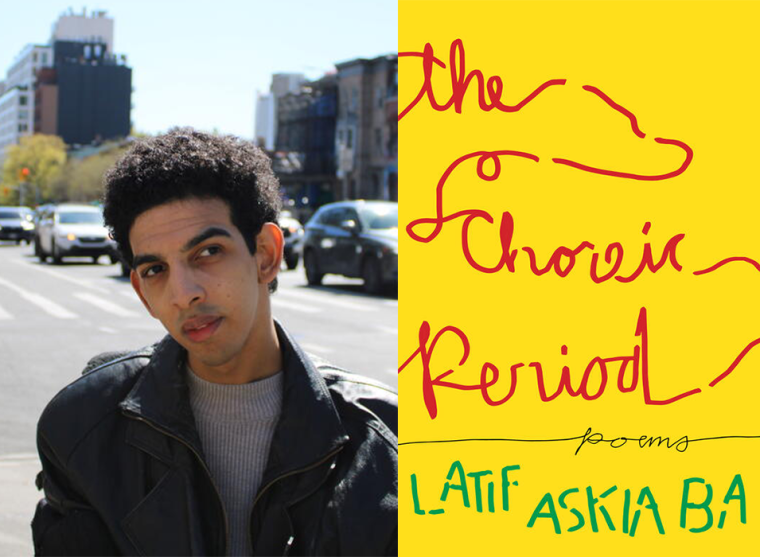

Latif Askia Ba, author of The Choreic Period. (Credit: Tarek Dekkaki)

1. How long did it take you to write The Choreic Period?

It took two years, give or take. I wrote this entry in my demon-journal that I kept in Dorothea Lasky’s Unleashing Your Poetic Demons seminar in 2021:

19 septembre

This body does.

Without. I could try

explaining it: a faucet

leaking boleros or

something soft like

ripe platanos or

the oil of ceeb

sitting in the family

bowl. Digging. Digging.

Digging. Why. Each word

has failed me. A new word

meaning not body. Or

something else

entirely.

I’ve been writing the word body quite a lot as of late. I’m not complaining or anything; I like the word, in fact. It comes from the Old English bodig or bodeg, meaning “body, trunk, chest, torso, height, stature.” But then things get very interesting at its Proto-Indo-European root *bʰewdʰ—meaning “to be awake” or “to observe”—the same root of the Pali word buddha (“the awakened”).

This is the earliest “period poem” I could find and, coincidentally, it has many qualities of the book (code-switching, French date, body-focused, playing with etymology, etc.).

During the same semester, while reading Gertrude Stein’s “Poetry and Grammar” for B. K. Fischer’s The Comma Sutra seminar, I laughed out loud at this thrilling sentence: “Commas are servile and they have no life of their own….” I found it refreshing to hear such strong sentiments towards punctuation marks. In the same essay she writes, “Periods have a life of their own a necessity of their own a feeling of their own a time of their own.”

True. So I really can’t say the book “took” two years…. The Choreic Period is a time! I was always writing it. In fact, rereading Stein’s essay I’m surprised that she mentions the time of a period—I totally forgot or was eluded by this detail the first time I read it. But that first reading made me determined to establish a poetic practice where I only used periods.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Trusting myself. i.e. Why am I only using periods? This is stupid and gimmicky. Blah blah blah. Doubt is part of the process—it can be helpful like radio static can be helpful, soothing or generative to the creative ear. I was lucky to be part of such an incredible cohort of poets who “got” my period poems and encouraged them.

It was also difficult in the beginning and middle of my “period practice” to not use other punctuation—kinda boring, you know? But after I finished the manuscript, I was still adhering to the same style and had to make a conscious effort to stop. I had become quite intimate with the periods; they became a natural expression. That’s precisely why I had to let go of them for the time being—too much resistance and I won’t write, not enough resistance and things become dull…this is Crip Poetics after all! I need form to break against.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Almost always in bed, on my belly, propped up on my elbows in order to stabilize (the involuntary movements, body, universe…).

Any time at any frequency. I don’t worry about it anymore. When I’m working on a project I usually write everyday—I mostly adhered to this regimen during the MFA program. Establishing a regular writing practice was extremely meaningful and healing—practice is a major theme in the book and in my life! Protect it at all costs!

But forcing is no good. By “forcing” I don’t mean writing when you don’t want to or when it’s inconvenient—those are often the best times to jot something down! Forcing is writing when you can’t…our body (mind included) is not shy about its limits. Rest, idleness, a break from stimuli, silence—and lots of dancing and singing are all necessary for the writing process.

4. What are you reading right now?

Larry Eigner’s Areas Lights Heights: Writings 1954–1989 (Roof Books, 1989), a collection of his prose (letters, essays, reviews). It’s beautiful to listen to him speak at length after reading his collected poetry. He’s such a rifter, the brevity and focus of his poetry is a little misleading. He could really go on and on with ease in a dazzling choreography. I’m also reading academic papers and critical essays about his poetry, which open up his work for me in so many new and exciting ways. I have to do all this to write my own paper on Eigner from a Buddhist perspective, and as the deadline approaches rapidly I find myself spending the majority of my days with Eigner—it’s an honor to commune so intimately with ancestors.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Sid Ghosh! He wrote the chapbook Proceedings of the Full Moon Rotary Club as a high school student. It’s one of my favorite collections of all time. I brought it into one of the classes I taught at Columbia and had them pass it around to one another so that each student got a chance to read a poem out loud. That book is magic—a powerful timebeing—it heals, it brings us together, it teaches us how to listen. Ghosh is a brilliant, diligent, revolutionary poet-philosopher-mystic that is already sharing his luminosity with the world.

6. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

Alan Gilbert, my dear thesis professor, and my workshop mates were my strategy! I already had a rough order based on feeling (of the poems’ energies) and prior experience compiling manuscripts, but nothing is quite like Alan’s ordering ritual, where all the pages of the manuscript are spread across a large desk (many desks pushed together) and we work together to slowly find the “right” order by swapping and re-swapping, grouping and regrouping, holding up poems gingerly between two other poems to see if there’s any chemistry there. Seeing the manuscript all at once across a flat plane in a single moment is tremendously informative.

But also, length, tone, mood, and transitions (end of a poem in relation to the beginning of the next) are the elements I pay most attention to when organizing any collection. In this collection though, titles were extremely important since there are many poems with the same names…. I didn’t think they wanted anything to do with one another, so I spread them out as much as possible.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

It was a great pleasure and honor to work with Chris Martin. Our paths and spirits were bound to cross since they very much rhyme, reflect, and refract. It wasn’t a specific word that stuck with me—but more his genuine belief and commitment to my work.

This shone through brilliantly in his editing. I love the editing process—editing as a metalanguage, a cypher, a patois. Just something as simple as adding a period where I didn’t think of adding it was very impactful. It showed that he took the time to live in the periodic syntax and knew how to lovingly wield it.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Choreic Period, what would you say?

Nothing. The period was always. Is always. Will be always. Would be always. Is being. Always.

(But also, don’t forget to get to bed early and drink lots of water.)

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of The Choreic Period?

Reading is a crucial part of my writing process—especially Disability/Crip Theory. I also love studying and practicing speaking different languages, but I try not to try too hard or take it too seriously or think in the able-bodied/colonial terms of “fluency” or “mastery.”

I also practice Buddhism…not sure what that means exactly, but that not-sure-ness is an essential part of my practice. From 2020 onwards (it’s difficult to say as I don’t believe keeping track of spiritual processes through normate chronology is very skillful) I felt like I was losing my connection to the Dharma (the Buddha’s teachings). I was so focused on writing and then on teaching, my already fickle meditation practice was pretty much dead…or so I thought.

I mean, I ended up writing a book that is practically an open love letter to the Buddha, to the Body, to Loving Awareness. So my practice didn’t really stop, it deepened. Now that I’ve established a more regular meditation practice with the support of a sangha (community), I cherish that period of doubt and solitude—it allows me to appreciate just sitting and being with the Body now. That’s a real privilege.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

“Just write.” —all my past-present-and-future teachers

Having a supportive community to keep you writing is important (seek one out or create your own!), but if you’re always waiting for a thumbs-up from that Person (we all have them), what are you going to do when they give you a thumbs-down? That Person can be yourself, by the way. Is it fair to expect constant validation from yourself? Is it even desirable? What if you write something that you don’t like…should you lie to yourself about it?

For me, writing is the validation. Sometimes I write something I like and sometimes I write something I don’t like. What are you gonna do? All you can do is pay attention to the process, the practice, and see what it does to you, what it does to the people around you, what it does to your dear readers.

To “just write,” you don’t have to know why, how, or even what. And you certainly don’t need to know how much. All you need to determine is where and when. If that feels overwhelming, then here and now is a good place to start…actually, it’s the only place to start!