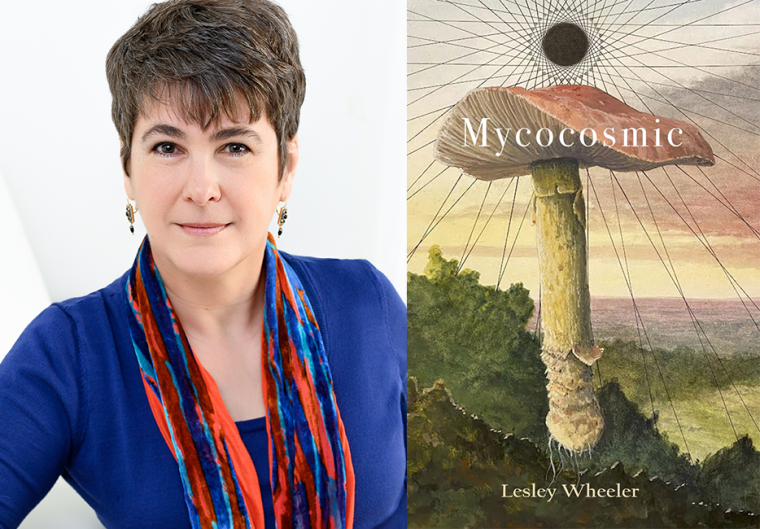

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Lesley Wheeler, whose poetry collection Mycocosmic was published on March 1 by Tupelo Press. Filled with intricately woven spell-poems—prayers, hexes, charms, and invocations—Mycocosmic calls for a transformation of language, grief, and the self. A parent’s death gives Wheeler the freedom to reveal difficult truths about family violence and her sexuality; a midlife mental health crisis transforms her sense of self. Incantatory language channeled through a wide variety of forms—including free verse, litany, sonnets, the bref double, the golden shovel, and the villanelle—empowers these shifts. Diane Seuss praises “Wheeler’s research, her feral witchery,” adding, “her poems themselves, are an answer, if not the antidote, to the state we’re in.” Wheeler is the author of five other poetry collections, as well as the essay collection Poetry’s Possible Worlds (Tinderbox Editions, 2022) and the novel Unbecoming (Aqueduct Press, 2020). Her work has been supported by Fulbright, the National Endowment for the Humanities, Breadloaf, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. Recent poems and essays appear in Poetry, the Massachusetts Review, the American Poetry Review, and Ecotone. She works as the poetry editor of Shenandoah, lives in Virginia, and teaches at Washington and Lee University.

Lesley Wheeler, author of Mycocosmic. (Credit: Anne Valerie Portraits)

1. How long did it take you to write Mycocosmic?

I had a dream in 2017 that a statue in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, one of those goddesses in the basement, came to life and ordered me to write a book about dragons. I didn’t obey her exactly—we’ll see if she punishes me—but I did start writing spell-poems involving fire. Most of the poems that made it into Mycocosmic, though, were written between 2019 and 2022.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Being brave. My mother died in April 2021, so the book contains some poems about her final illness and ways I wish I’d taken better care of her. What came after, though, felt revolutionary: I became able to write about family violence, sexuality, and mental health more frankly than before, because I knew she wouldn’t read the work. I hadn’t realized how much I was holding back.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’m busy teaching undergraduates from September through May, but the great thing about poetry is that you can throw down a draft in a stolen hour. I used to like late afternoons on campus, when class ended and my spouse was doing his childcare shift, but now that the house is quiet, I prefer mornings at my home desk with a pot of chai. I don’t follow the excellent advice to write every day except during academic breaks.

4. What are you reading right now?

Recently, Honor Moore’s A Termination (A Public Space Books, 2024), Heid E. Erdrich’s Verb Animate (Trio House Press, 2024), and Sylvia Jones’s Television Fathers (Meekling Press, 2024). Right now, Jan Beatty’s Dragstripping (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2024) and Marianne Moore for class. On deck is Denise Duhamel’s Pink Lady (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2025). Late at night I read mysteries. At this political moment it’s easier to sleep after immersion in absorbing tales in which justice is served.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

If I had to choose one I’d say Cynthia Hogue, who writes gorgeous poems about illness and the spirit. But there are many well-respected poets doing tremendous work that doesn’t rack up big sales figures or command all the prizes. I’m rooting for their team.

6. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

Here I have to thank another strong poet, Jeannine Hall Gailey, who read a draft I thought was done. She informed me that I had buried the most powerful, risky work. Although this made me grumpy, I realized she was right. I gave up the original title, “Good Things Come Through Fire,” which was problematic anyway in this era of wildfires, and elevated the mycelium motif. Then came the brainstorm to write an “underpoem,” an essay in verse that would run through the whole book along the bottom of each page. That’s when the pieces clicked together.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

When Jeffrey Levine called with an offer to publish, he said he felt attached to Mycocosmic because he was the reader who first plucked it out of the submission pile. His confidence in the book mattered.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Mycocosmic, what would you say?

This isn’t writer-stuff, it’s life-stuff that bears on the poems: The doctors aren’t giving you the straight story, your mother is dying, so prioritize her quality of life instead of that mad dream of rescue. And, former Lesley, stop volunteering for so many committees.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Mycocosmic?

Serving as poetry editor of Shenandoah has made me ruthless about my own writing, in a helpful way. I read so many good submissions; the poems that make it through the ridiculously narrow publication funnel move and surprise me in some unforgettable way. That’s the bar. Otherwise, caretaking, teaching, reading, cooking, studying Tarot during the pandemic, and learning to pray even though I don’t know what I believe in, except for goddesses in basements.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Persist. Chase Twichell told me at a writing conference once that good books can take years to place, but if you keep trying, eventually the right editor will fall in love. (She also told me to cut a self-indulgent Hamlet poem from my manuscript, which surely helped.)