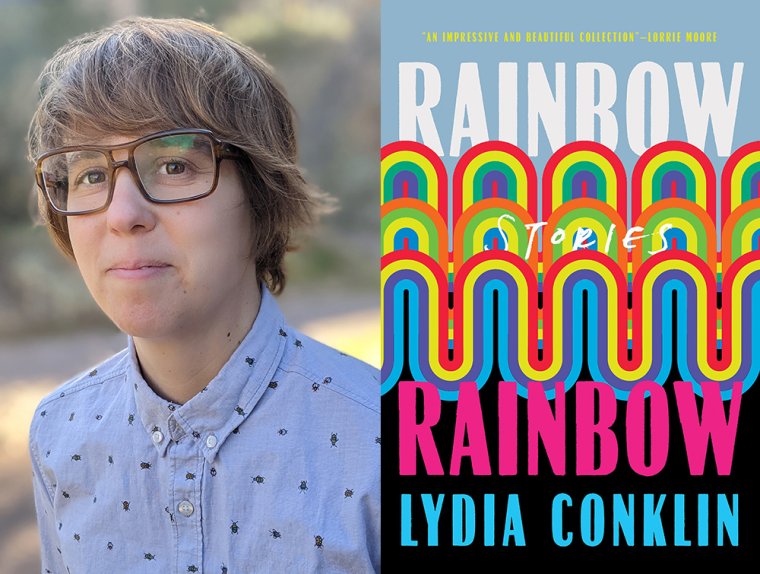

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Lydia Conklin, whose debut story collection, Rainbow Rainbow, is out today from Catapult. In these narratives, characters find themselves in liminal spaces or on the cusp of change across multiple generations, seeking self-understanding, love, and belonging. Adolescents come of age in the real world and on the internet, where they wrestle with the difficulties and pleasures of embracing their queer identities. Adults spark relationships with surprising people in unexpected places or weigh the costs of parenthood. And travel abroad fuels revelations about the challenges faced by queer people outside the United States. Melissa Febos calls Rainbow Rainbow “a gorgeous ode to queer life in all its awkward, tragic, hilarious, erotic, and joyful forms!” Conklin is an assistant professor of fiction at Vanderbilt University. They have received a Wallace Stegner Fellowship from Stanford University, a Rona Jaffe Writer’s Award, three Pushcart prizes, and fellowships from MacDowell, Yaddo, and Hedgebrook, among other honors.

Lydia Conklin, author of Rainbow Rainbow. (Credit: Emily Ray Reese)

1. How long did it take you to write Rainbow Rainbow?

I started writing the oldest story in the book, “The Black Winter of New England,” in 2010, so it’s twelve years old. I finished the first draft of the newest story in the summer of 2020, in the darkest period of the pandemic. I have worked on other projects along the way, but all in all the book took twelve years—and twelve wild years at that.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

One of the hardest parts for me was learning how to inhabit characters who behave differently from me. Every character has a piece of me in them, but many of the characters behave at times in ways strikingly different from the way I would behave. The hardest character was Lisa Parsons in “Ooh the Suburbs,” who behaves in some pretty shocking ways. I was on the other side of that story as a child—aligned with Heidi, the protagonist—so it took work for me to inhabit Lisa and try to show that she has dimensionality and experiences pain like anyone else, even if she behaves in immoral ways.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write while walking, at a treadmill desk. This was the greatest innovation for me in the pandemic. I’m a very restless person, and I get ideas while in motion. So it’s helped me open up my thinking so much. The wall in front of the desk has many postcards with pictures that remind me of a broader world—pig farmers under a tangled tree, fish giving birth to other fish, walleyed kittens in baskets, a Polish Airlines sparrow. I start writing every morning and write until there’s something else I have to do—a job or familial or social obligation. If I have nothing, I try to write until two hours before sunset, when I go for a swim or a walk. But especially now, I always have something that interrupts me early.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m in the midst of so many amazing books that have just come out. I’m reading Out There by Kate Folk, a brilliant and eerie story collection, and The School for Good Mothers by Jessamine Chan, which I read in all its brilliance in manuscript form some years ago. And I just finished Second Place by Rachel Cusk which I adored every minute of. I listened to it while painting a room, and it made the job actually fun. I didn’t even get sick of the color green.

5. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Rainbow Rainbow?

I have been surprised and interested to see how careful readers spot resonances through the stories that I hadn’t noticed. Recently an interviewer mentioned that all the characters are pioneers in some way, which felt so true, and I love that someone else told me that. I didn’t notice until putting all the stories together that they all deal with transitions: not just gender transitions but other types of life transitions, like moving to cities, ending relationships, and beginning sobriety.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Technology! I am thankful for my computer and my treadmill desk but enraged by the internet and my phone. I have to lock up my phone every day—in a box designed for locking up cookies—during the hours I’m writing. Text messages ruin me.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

My genius editor, Leigh Newman, helped me so much with endings. Two stories had endings that were too similar, so I had to change one. Another story had an ending that never worked, so she just cut it, and it was magic! Yet another story, “Sunny Talks,” just wasn’t getting to the emotional heart enough at the end. The original ending was about Sunny, the secondary character, but it needed to be about the narrator—what they wanted, finally, from the world. Leigh pushed me to find that and made it such a better story.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Rainbow Rainbow, what would you say?

I would tell myself to take my time, that it would take a long time to write a good book and that that was okay. That people would wait, that supporters would still be there when it was ready. I had a lot of anxiety about how long it was taking me to publish my first book. Now that it’s happening I feel so much relief, but I’m also so glad I didn’t try to publish it before it was ready, though I was tempted to do so many times.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Rainbow Rainbow?

Time had to pass, and the world had to change. Some of the power of the stories in this book comes from the fact that the characters are figuring themselves out in the context of such radically different cultural and political eras. The characters living during the years of Bill Clinton’s presidency have different—but no more or less severe—obstacles to their happiness than the characters who are wrestling with being queer and trans after the 2016 election or in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

The best piece of writing advice was given to me by Lan Samantha Chang, about the first story in my book, “Laramie Time.” There is a moment in which the main character is told a story by her sperm donor. In the draft Sam read, she noted that the narrator’s reaction wasn’t the most interesting emotional choice I could’ve made. That one simple sentence changed everything and broke open the story for me. I think about her words all the time. A similar and similarly resonant piece of advice was given to me—about my novel—by Elizabeth Tallent, who noted that, in certain moments, “room for thornier emotion abounds!” I loved that exclamation point and the mindset of creation and growth and expansion instead of looking at what was wrong with the manuscript as a deficit to be fixed. She allowed me to see revision as an adventure to embark on.