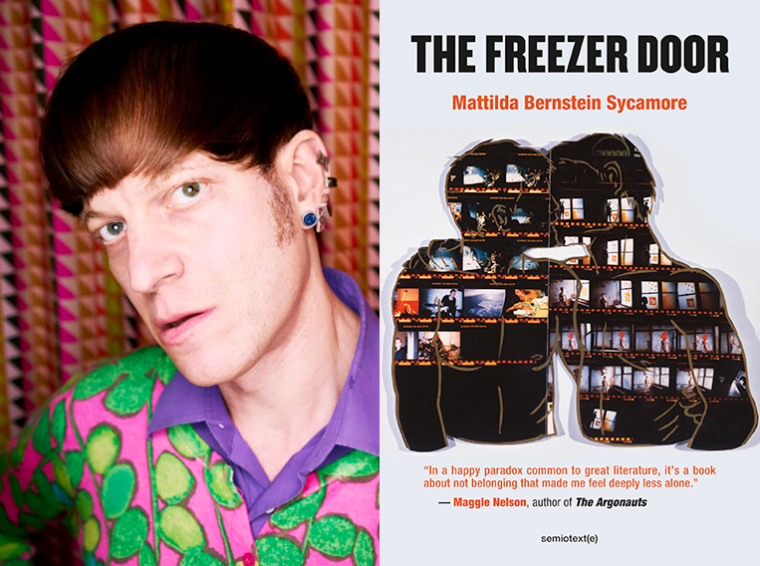

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, whose latest nonfiction book, The Freezer Door, was published in November by Semiotext(e). From Seattle’s Volunteer Park to local gay bars, Sycamore roams in search of intimacy. Yet the American city in the contemporary age seems to deny connection at every turn, as gentrification, consumerism, and fear encroach further and further upon daily life. Even in queer spaces and communities that once felt familiar, she finds herself increasingly alienated. Shifting between various scenes and timelines, Sycamore mourns sites of brokenness, but also discovers glimmers of humor, pleasure, and new language along the way. She keeps moving, despite everything, finding new ways to be alive. “I really love Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s The Freezer Door,” writes Maggie Nelson. “In a happy paradox common to great literature, it’s a book about not belonging that made me feel deeply less alone.” Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore is the author of several previous books, including the novel Sketchtasy (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018) and the memoir The End of San Francisco (City Lights Publishers, 2013), which won a Lambda Literary Award. Her writing has also appeared in BOMB, Bookforum, Fence, n+1, and Ploughshares, among other publications. She lives in Seattle.

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, author of The Freezer Door. (Credit: Jesse Mann)

1. How long did it take you to write The Freezer Door?

This is such a tricky question because, in a way, I think every book I write is informed by my whole life. But I started writing the text that became The Freezer Door around 2012, when I moved to Seattle. I think I wrote most of it between 2014 and 2017 and finished the final draft around 2018? But then of course I was still editing for another year, until it was sent off to the printer. So six or seven years. In the literal sense. There are other senses of course, but I don’t want to get too confused.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I think the hardest part was living it. So much of the book is about searching for intimacy in the places and spaces that work so hard against connection, even if that’s what they’re supposed to be for—the book is about staying present in this search anyway. And this can be so painful.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write every day in my apartment at the computer screen, and I write in my head when I’m walking around, and I write on Twitter, where I can look at text out of context. But I don’t have the routine that so many writers talk about, where they get up in the morning and have a certain number of hours or whatever. I deal with devastating chronic pain drama, and have for years, so sitting and staring at the computer for a long time is not an option. Sometimes I wish it were, but also knowing that I have to move around does help me to think in different ways.

4. What are you reading right now?

Right now I’m reading Bloomland by John Englehardt, which uses a second-person narrator to engage the minutia of intimate and interpersonal trauma—I’m thinking about this quote at the moment: “The accident by which people die is the same accident by which they live.” And also this existential question: “Are you in a good cage, or a bad one?”

And I just finished Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own by Eddie Glaude, who writes, “If the condition of the love of country is a lie, the love itself, no matter how genuine, is a lie.” We all need to pay attention to this, in this country of violence.

I also just finished Sarah Dowling’s Entering Sappho, which is such a beguiling collection of poems because it lures you in with a research-based process that almost invokes a kind of American regionalism paradoxically infused by town names drawn from ancient Greece, and then pulls you into “pseudo-translations” of Sappho’s poems with such an incredible rhythm and inside the rhythm are the questions of whether desire can ever truly exist outside violence and whether colonialism is always in the anthem.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Dionne Brand is a genius.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Dealing with devastating chronic health problems. For example, I was just on a roll with answering these questions, and then my head went blank. This often happens after fifteen minutes at the computer, even if I have an entire essay in my head beforehand. So I constantly have to go back and forth. There are so many days when I can only write a few sentences, but a few sentences every day builds into a surprising amount, actually.

7. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of the book?

I think the work of staying in my body. The work of not giving up on the dream of the city as the place where you will find everything and everyone you never imagined, even when that dream has been squashed by gentrification, consumerism, technology, surveillance, and the stranglehold of the suburban imagination over urban life.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Freezer Door, what would you say?

When I start working on a new book, I like to write without an intention of what I want it to become. So that the writing itself creates the form. I don’t think I would go back.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I don’t have a single most trusted reader. I have a number of writer friends who always give me invaluable feedback on my manuscripts, but everyone has something different to offer and I always want multiple viewpoints—the more the better. And I can’t ever trust anyone completely, right? Not with my own work, I mean. Doesn’t it have to be that way?

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Everything you’re most afraid of is what you need to write.