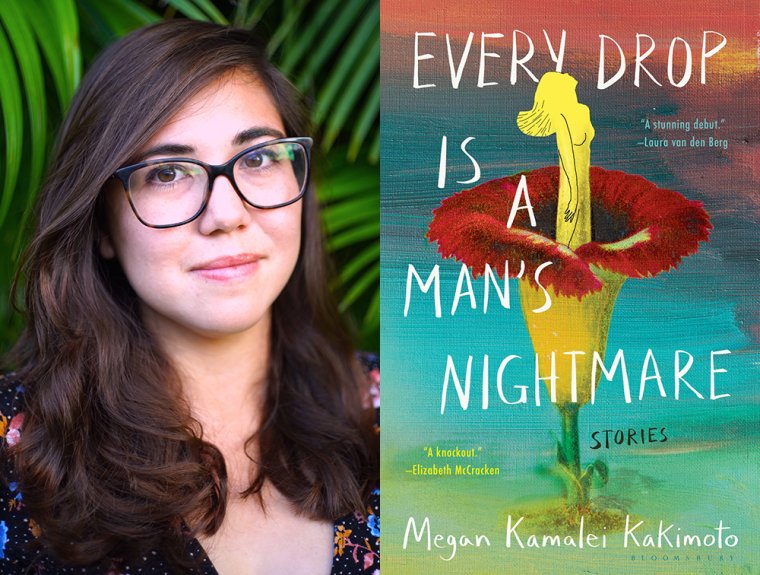

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Megan Kamalei Kakimoto, whose story collection, Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare, is out today from Bloomsbury. This haunting debut confronts the physical and mythological terrain of Hawai’i, deconstructing its status as a tropical dreamscape to reveal a thornier topography shaped by the politics of colonial conquest and its aftermath. Female characters of mixed native Hawaiian and Japanese descent are at the forefront of these stories, walking the tightrope between the expectations of mainstream American culture and the specific norms and taboos of their heritage and family dynamics. The opening tale recalls Jamaica Kincaid’s famous “Girl” in its overwhelming list of directives and guilt-inducing questions from mother to daughter: “After everything that has happened to us, don’t you want to make your father so proud?” The pains of adolescence, love, sex, grief, nature, the supernatural, and metacommentary on the writing life all find their way into these narratives, equal parts sensual and cerebral. Publishers Weekly praises the book: “Marked by a wry sense of humor and an unerring touch for the surreal, Kakimoto’s stories add up to a powerful exploration of gender, class, race, colonialism, and domestic violence. This eloquent outing marks Kakimoto as a writer to watch.” Megan Kamalei Kakimoto is a Japanese and Kānaka Maoli (native Hawaiian) writer. Her fiction has been published in Granta, Conjunctions, Joyland, and elsewhere. She has been a finalist for the Keene Prize for Literature and has received support from the Rona Jaffe Foundation and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. She received her MFA from the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas in Austin, where she was a fiction fellow. She lives in Honolulu.

Megan Kamalei Kakimoto, author of Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare. (Credit: Van Wishingrad)

1. How long did it take you to write Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare?

I wrote the stories in Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare over the course of four years, though the oldest story, “Temporary Dwellers,” dates to 2016. I like to think the version that emerged out of revising the collection as a whole is vastly different from its first-draft iteration, though perhaps I’m too close to the project to see this objectively.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

By far the biggest challenge of seeing Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare through to completion was pushing past the brick wall of my fears and anxieties over how these stories would be received. In the contemporary publishing landscape, there are so few native Hawaiian writers being published, so I felt an enormous responsibility to do right by not only my fellow Kānaka writers but also the Hawaiian community as a whole. The characters in Every Drop are inextricable from their Hawaiian roots, with Hawaiian mythology and superstitions permeating every story in the collection. I felt deeply overwhelmed thinking about how this book needed to speak for a particular Hawaiian experience, which is absurd, since there’s no such thing as a monolithic “Hawaiian” experience. Yet this is a consequence of writing on the periphery of a marginalized experience—it’s very hard to unburden ourselves of the expectations we imagine our communities have for us, simply because there are so few of our voices being championed in the first place.

So writing past the fear, or maybe into the fear, of an imagined readership and its criticism was a challenge I wrestled with throughout the writing, editing, and now publication process. I imagine it’s something I’ll encounter for a while longer, or at least until we see more Kānaka writers platformed and supported in the publishing industry.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’m most content when I’m writing every morning—the last three years of my MFA had afforded me this gift of time. Now that I’ve graduated and am balancing a work schedule, I still try to carve out a consistent writing routine, waking at 6:30 AM to get in a couple hours of work, then reading and revising in the late afternoons. Consistency works for me; I feel grounded, fulfilled, and at peace when I can return to a project morning after morning. I also love the romantic ideal of writing in coffee shops, though, to save money, I’ve mostly been writing at my home desk.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m an avid rereader and am trying to make some headway with my novel in progress, so I’ve been rereading a lot of books I admired on the first read and hope to be in conversation with. These include Territory of Light by Yūko Tsushima, Motherhood by Sheila Heti, Savage Tongues by Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi, The Need by Helen Phillips, Intimacies by Katie Kitamura, The Incendiaries by R. O. Kwon, The Quick and the Dead by Joy Williams, and America Was Hard to Find by Kathleen Alcott. An eclectic range, I know, which I imagine (and hope) will feed into a very strange book.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

This book would not have been possible without the works of Kiana Davenport, T Kira Māhealani Madden, and Kristiana Kahakauwila forging a path for Kānaka Maoli writers. On the sentence level, I’m always studying work by Toni Morrison, Joy Williams, Lorrie Moore, and Amy Hempel; they make me strive to become a better writer.

I try to keep a stack of books on my desk whenever I’m working on a new project. For the collection, I kept close Autobiography of Red by Anne Carson, Jesus’ Son by Denis Johnson, The Dark Dark by Samantha Hunt, Tender by Sofia Samatar, Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz, Sabrina & Corina by Kali Fajardo-Anstine, Stranger Things Happen by Kelly Link, Black Light by Kimberly King Parsons, and a handful of others.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I think if you’re clear in your intentions of what you hope to get out of an MFA, it’s worth pursuing, though by no means do I believe it to be an author’s singular path to success. For me, I was burned out working a PR job that drained all my creative energy, and I longed for a literary community in which to immerse myself. All signs pointed toward an MFA, so long as I wasn’t going into debt for it. Pursuing the MFA at the Michener Center for Writers proved to be one of the most significant and meaningful creative experiences of my life.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Both my agent, Iwalani Kim, as well as my editor, Callie Garnett, were invaluable partners in ushering this collection into the world. Their constant reassurances about my small questions and concerns, though it shouldn’t have surprised me, really put so much of my anxiety at ease throughout the often nebulous path of publishing.

8. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare?

Moments of surprise were by far the most delightful when writing these stories, particularly when a character would do something unexpected or outlandish, something at which I would otherwise cower or maybe resist. I think that’s so much of the pleasure of writing for me, the opportunity to be fearless on the page. I’m a people pleaser by nature, which doesn’t afford a lot of room for fearlessness.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

To manage the aforementioned anxiety of writing this book, I ran constantly. I signed up for the Honolulu Marathon to give myself a goal to work toward that had nothing to do with world-building or sentence-making. Then I got injured. I took to rhythmic cycling classes, which were easier on my knees and on which I continue to lean while navigating the anxieties of bringing a book into the world.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

I think a lot about something Kimberly King Parsons and Chelsea Bieker taught in their class called “Rejection, Revision, and Renewal,” especially as I move into promoting the collection. I even wrote it on a note card and taped it to my desk: “Keep your head down and shut out the noise, because nothing beats a good writing day.”