This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Miller Oberman, whose poetry collection Impossible Things is out today from Duke University Press. The book offers an intimate account of intergenerational grief and explores Oberman’s experience as a transgender child and father. Oberman integrates passages from his own late father’s unpublished memoir, employs experimental poetic forms, and leverages queer and trans theory to complicate and broaden discourse on fatherhood and masculinity. Ellen Bass calls the collection a “compelling extended elegy” and adds, “Honoring both what’s missing and what remains, Impossible Things is a stunning book you will want to read, reread, and keep close.” Miller Oberman is also the author of The Unstill Ones (Princeton University Press, 2017) and has received a number of awards for his poetry, including a Ruth Lilly Fellowship, the 92Y Discovery Prize, a NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellowship, and Poetry magazine’s John Frederick Nims Memorial Prize for Translation. Oberman teaches writing at Brooklyn Poets and at Eugene Lang College at the New School in New York. He is also an editor at Broadsided Press, which publishes visual-literary collaborations. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, Poetry, the London Review of Books, and elsewhere.

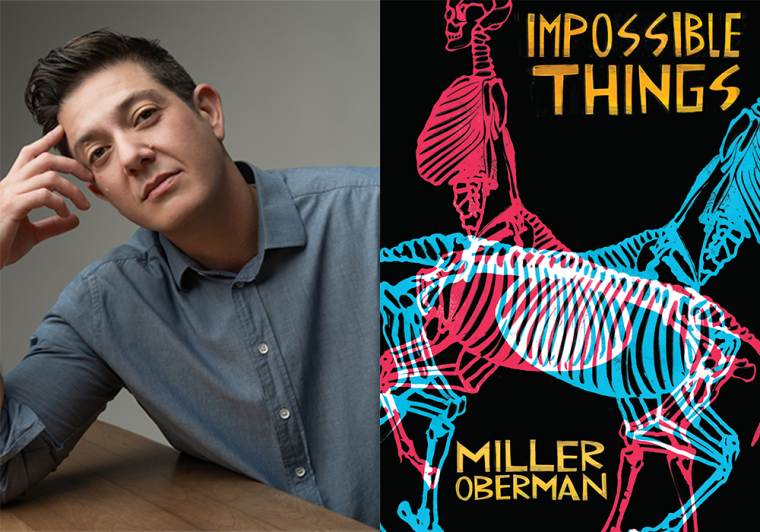

Miller Oberman, author of Impossible Things. (Credit: Beowulf Sheehan)

1. How long did it take you to write Impossible Things?

I began work on the poems in Impossible Things in early 2017, so one answer is seven years. But some of the poems in the book I’ve been trying to write for much longer—in fact, two poems (“Theory” and “Joshua Was Gone”) I was drafting as early as the first writing workshop I took as an undergraduate. I haven’t been working on them consistently since then, but I always hoped I’d be able to get them right, and I think I finally did.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The book includes erasure poems from an unpublished and unfinished memoir my father was working on before he died, and I think figuring out what form those excerpts from his writing would take was really tricky. It was crucial to me to share his language and be in conversation with him, but it took many different experiments to figure out how best to do that.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’m so jealous of writers who write in public spaces like cafés and I’m just not one of them! I need a lot of solitude to write. I really feel what I’m writing while I’m writing it, and sometimes I need to pace, explore language and rhythm out loud, make a big mess with a stack of books I’m drawing inspiration from, cry or laugh out loud, etc. I need to be somewhere I can be vulnerable, open, and undisturbed. I really get into a zone. I’m a very streaky writer. I’ll often taken brief notes throughout the day in a notebook or on my phone, but for the actual business of writing and revising, I usually go on a few DIY style retreats throughout the year, just to anywhere cheap or free where I can work without interruption. I wrote most of Impossible Things in the Catskills at my partner’s beloved grandparents’ house, where I’d go and work for three to four days straight a few times a year. Their memories were absolutely a blessing to me—even though they are no longer on our plane—it gave me such strength to work at Louisa’s grandfather Moishe’s desk, looking out at her grandmother Millie’s flowers. And, of course, at the mountains.

4. What are you reading right now?

There are writers who I’m sort of never not reading. Paul Celan, Lucille Clifton, Hart Crane, Kiese Laymon come to mind. And there are so many amazing contemporary poets right now—I’m reading some new favorite poets with breathtaking new books out this year: Omotara James’s Song of My Softening (Alice James Books, 2024) and Joan Kwon Glass’s Three Gone Kingdoms (Perugia Press, 2024) have been sustaining me this month. I’m a huge fan of Candace Williams’s new book, I Am the Most Dangerous Thing (Alice James Books, 2023). I’ve also been reading, like so many of us are, Mosab Abu Toha’s miraculous and devastating Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear: Poems From Gaza (City Lights Books, 2022).

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

This is an impossibly hard question! There has been a lack of support for and suppression of the voices of BIPOC and queer and trans writers for many, many years in the American poetry scene. The number of writers who have not had enough or any recognition by literary organizations and the publishing industry is just staggering and makes it inconceivable to me to mention a single name. But what I’m thinking of today and over the past year is the terrible lack of voices of Palestinian writers telling their own stories. These writers, in all genres, are making amazing, crucial work, and so much of it does not reach us.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

I truly don’t know how to answer this question! My first impulse is to say being the parent of two small children. They are always here and are not overly quiet. But I don’t think I’d have written this book at all without them. They were such a huge part of the drive to write it, and I learn so much from them every day about how to be a living human being, which also means they teach me how to be a poet. In truth, the impediment to all writing is just the right kind of time and space—there is never enough of it!

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

I asked for permission from a large press to use a poem in my book, and they said yes, but that the permission only lasted ten years. I thought this was great! But my wonderful editor, Ken Wissoker, gently advised me not to do this, because he told me my book would be in print for so much longer than ten years. This had not crossed my mind, which maybe sounds silly. But it was incredibly moving to me to imagine this book might still be read ten years or more from now.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Impossible Things, what would you say?

Ha! I am really into this form called a cento, which is a poem made entirely of lines from other poems. Highly recommend! But. My advice to myself would be, Miller: Keep better notes when you’re writing centos, or else you’ll spend hours and hours retracing your steps so that everything can be cited properly.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Impossible Things?

Reading, always. But beyond that, for this book in particular, the most important work I did was self-work. I started this book in earnest after my first child was born, and I began realizing how much I’d been impacted by having a father who’d lost a child. This took an enormous amount of unpacking and processing in therapy and with my partner. I don’t think I’d have written this book without my therapy or EMDR practice, which is a deeply poetic process. It truly mirrors so much of my understanding of the lyric in that it asks you to go into a memory or experience and essentially stop time so that you can look at it and change it or change your perspective of it in an endless number of ways. This practice allowed me to grapple with painful memories and experiences and relate to them in new ways. I’m laughing at myself slightly here because “exciting new ways to experience pain” sounds like such a capital-P poet thing to say. I’ve heard people describe writing as therapeutic, and I’ve never thought that for myself, but I do think that therapeutic modes can enhance artistic work enormously, because they give us access to our inner workings in fresh, sometimes even revelatory ways.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

The wonderful poet Alice Friman told me that a poem is a ghost and the words are the sheet you throw over the ghost so you can see it. “You can never see the poem,” she said. “It’s invisible. The best you can do is make your words, your sheet, as sheer as possible, to glimpse it.” She also told me (and you have to imagine this in a very heavy New York accent), “If you’re kissing JoJo behind the barn, and you have an idea for a poem, STOP KISSING JOJO.” Sometimes, when I see a writer sitting somewhere furiously writing (all you public space writers!) I also picture some sad JoJo abandoned by a barn.