This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Morgan Talty, whose novel, Fire Exit, is out today from Tin House. In this tale of complex interpersonal relationships, belonging, and family secrets, a white man named Charles yearns for contact with his daughter, Elizabeth, a member of the Penobscot Nation—just across the Maine river from where he has quietly watched her grow up. Although he was raised on Penobscot territory, where he lived with his white mother and his Penobscot stepfather, Charles was forced to leave due to his lack of Penobscot blood. After Mary, a Penobscot woman, becomes pregnant with Elizabeth, Charles was asked to stay silent about his paternity. But forces eventually conspire to bring Charles back into Mary’s and Elizabeth’s orbit, dramatizing the long reach of colonial violence in the United States, which through biopolitical tools like racial categorization continues to weaken social ties and mutual affection—even among those who should be closest. The Associated Press praises Fire Exit, in particular its “gripping ending to a thoughtful, heartfelt exploration of what it means to be part of a family and a community.” Morgan Talty’s debut story collection, Night of the Living Rez (Tin House, 2022), won the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize, the American Academy of Arts and Letters Sue Kaufman Prize, the National Book Critics Circle John Leonard Prize, and the New England Book Award. Talty is an assistant professor of English in creative writing and Native American and contemporary literature at the University of Maine in Orono.

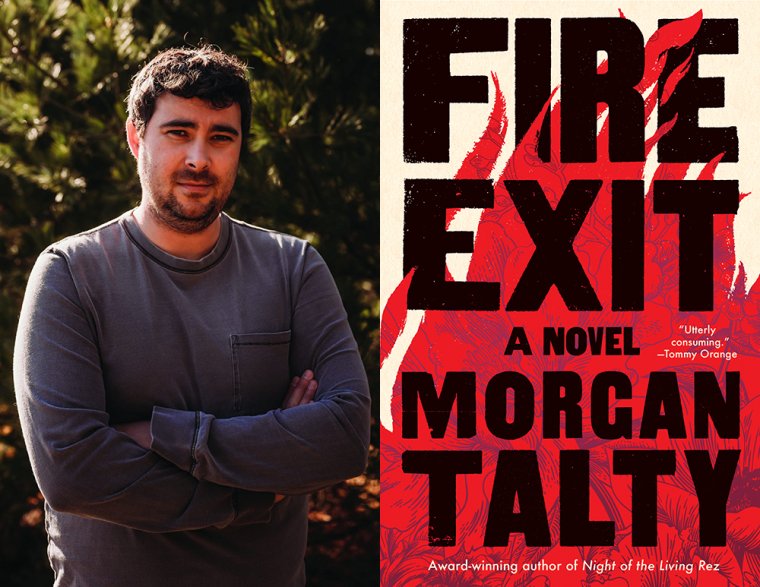

Morgan Talty, author of Fire Exit. (Credit: Tin House)

1. How long did it take you to write Fire Exit?

It took almost six years to write, a little more than six if you consider the editing process with my wonderful editor, Masie Cochran. But the idea of the book—or the engine of the novel, the very inexplicable situation that sparks the opening line of the novel—came to me in 2015. If percolating counts, then eight years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Finding the right point of view, then developing Charles’s character in a way that affected the story but made room for the story to affect the characters, which, in my view, helped deepen the emotion I felt for them (and for the reader as well).

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I have a room in our house where I write now; it’s my temporary office until we can get a shed built where I plan to work. Before I had a child I was able to write whenever, but that’s harder now. I am fortunate, though, to have Jorden, my wife—who is a “retired” teacher and now a stay-at-home mom—by my side so that I can go and write in the upstairs room. Without her I wouldn’t be getting anything done. Really.

4. What are you reading right now?

Delinquents and Other Escape Attempts: Linked Stories by Nick Rees Gardner, which is forthcoming in August from Madrona Books. I’m not reading it for the first time; I’m on my second read. It is a brilliant collection. A much-needed addition to contemporary literature, it offers both a searing critique of societal failures and a compassionate portrayal of human resilience in the face of addiction.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Every book I read I annotate, trying to figure out the logic of the story. Some stories are easy to figure out, meaning I can make a solid, concrete argument for how the writer achieves something like emotion. But some stories are harder, and then there are stories whose logic I can’t figure out. Those writers, the ones who create work I can’t figure out, are the ones I return to time and time again, the writers whose work will last for a long, long time. I’m talking about the greats, of course: Toni Morrison, Alice Munro, Anton Chekhov, Denis Johnson, and the many others who have left us with stories. For the living writers today, I can list a dozen whose work will be remembered for years to come. But when it comes to rewriting one version of Fire Exit, I was reading Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, which taught me a few things.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Fire Exit?

How intimately I knew these characters. It was like I spent my life growing up with them. I knew their histories, their secrets, their desires. This came from having spent so much time writing about them.

I’ll also add that after finishing the book and spending quite a bit of time away from it, I couldn’t remember parts of the book because I kept recalling moments from earlier drafts that got cut! And so when I reread the final version I received, I recognized it all but also saw the roughly fifteen hundred pages of cut material and scenes lurking in the shadows, so to speak. It was a surreal experience.

7. What is one thing your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

When talking about the final major change we made to the book, my editor, Masie Cochran, and agent, Rebecca Friedman, both said to me, “Just let it go, and you’ll see the story is still there.” They were right.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Fire Exit, what would you say?

“Have fun, loser.”

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I did research into the mental health aspects of the book, particularly electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). But the real work was having to keep the work alive in my head while I was not writing. That was the hardest form of work.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

I gotta go with what Rick Bass said to me: “Make something inexplicable happen, and then work to reconcile it, to make sense of it, while being specific.”