This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Navid Sinaki, whose debut novel, Medusa of the Roses, is out today from Grove Press. This queer literary noir is the story of Anjir and Zal, two childhood friends who fall in love as adults in Iran, where being openly gay is criminalized, and the government’s apparent acceptance of trans people requires them to surgically transition and pass as cis straight people. After Zal is attacked for being seen with another man in public, Anjir is determined to carry out their plan for the future: Anjir, who’s always identified with the mythical gender-changing Tiresias, will become a woman, and they’ll move to a new town for a fresh start as husband and wife. But Zal’s subsequent disappearance sets Anjir on a quest to find the other man, hoping he will lead to Zal. “Very rarely does a book come along that you feel might save lives, including your own,” writes Porochista Khakpour. “Medusa of the Roses is the most dynamic literary debut, certainly of the Iranian queer canon, I have ever read!” Navid Sinaki is an artist and writer from Tehran who currently lives in Los Angeles. His works have been exhibited at museums and art houses around the world, including the Lincoln Center, British Film Institute, Cineteca Nacional in Mexico, and the Modern Museum in Stockholm.

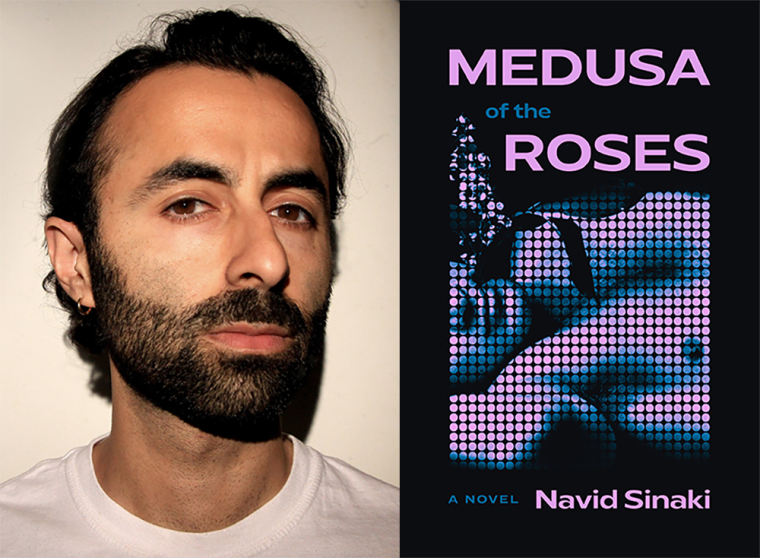

Navid Sinaki, author of Medusa of the Roses.

1. How long did it take you to write Medusa of the Roses?

I was born in Tehran because my parents, Persian émigrés living in the U.S., wanted me to be born where they were born. If they waited another month, I’d have been a Miami baby. Instead, they packed up and returned to their motherland. Eight months pregnant, my mom arrived in Tehran during the Iran-Iraq War. My sister remembers windows shattering during air raids. “We’d go from room to room to count which windows were still intact and which ones were broken.” She talks about it like it’s a funny anecdote to share, nothing more. After one bombing too many, my parents decided to take me (age one) and my siblings back to the U.S., this time settling in Southern California.

We would visit Iran often during the summer. I dreaded these visits because I was an anxious kid and because I always missed out on the larger pop culture phenomena that my classmates went on and on about during the first few weeks of school. I pretended to get references to The Matrix once September came around. “That red pill, am I right?”

Before landing in Imam Khomeini airport in Iran, the pilot always announced a final warning. At that point, people took the last swig of their drinks, and women put on their scarves. My siblings and I would play a game of chicken. We flew with a few items we thought would be contraband once we arrived. One time, my sister brought along her TLC CD, my brother lugged copies of Sports Illustrated, and I carried many books. We usually chickened out and left behind our goods on the plane, tucked next to the barf bags. CrazySexyCool was a sultry enough album title, so my sister discarded her CD. The Sports Illustrated magazines had swimsuit issue ads, so that was a no-go too. Even though I could argue The Story of O was an Oprah biography, I left my book behind just in case.

I was twenty-one the last time I went to Iran. I knew it would be my final visit, since I’d started making experimental films that were unabashedly queer and Persian. Returning to a country that criminalizes homosexuality was not in the cards for me. Because I knew it would be my final visit, I was focused on what I would take back to California with me. There were always some trinkets: gawdy jewelry, ceramic bowls, and Persian rugs. I was mainly there to research Iran films from before the Islamic Revolution—titillating, campy melodramas that were a shock to discover. They existed as copies of copies, films filmed off movie screens, slapped with subtitles, refilmed until the picture was a sliver of what it once was. This final trip to Iran began my entry into Medusa of the Roses. At twenty-one, I wondered what it would be like if my family never left Tehran. Would Pauline Réage still have made her way into my life?

My novel began as many snakes searching for a head. I had a series of e-mails I wrote in Iranian Internet cafes, always pay-per-minute, to my closest friend and the guy with whom I’d had an amazing first date the day before my flight to Tehran. There was something sensual about my final trip. In retrospect, it was likely because we hadn’t visited in a few years. Now as someone aware of his homosexuality, I really took notice of the men. I showed up in modest clothes, rather than the tight pants I stole from my sister during the indie sleaze era. But the young men in Tehran were dreamy in a way I didn’t notice as a nerdy teenager, before I started fluffing out my hair and listening to the Velvet Underground.

It took me close to a decade to finish this novel because I felt a certain weight. At the time I thought it was pressure to document a culture and place. It eventually became about documenting who I was at that moment, a portrait of the intensity with which I felt, loved, and lusted.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

My challenge has always been about knowing when to let go. Growing up, my mom loved fake statues. She purchased a topless Venus for our front yard, and decorated the nearby palm trees with blue Christmas lights. She painted faux cracks on columns she bought in bulk, before glazing them and putting distressed neoclassical urns up top. We had a tacky Cupid water fountain in our garden. To me, it was a magical fountain. If ever I found a penny with my birth year on it, I used it to make a wish. The pennies would always go missing. Perhaps it was my fairy godmother taking the coins out of the fountain. (It was my brother who stole the money.) I decided to try to trap my fairy godmother by filling the water fountain with red Jell-O, hoping the gelatin would solidify while my godmother’s hand was in the water. The result was a mess. It took me hours to scrape the gunk out of Cupid’s throat when my parents realized what I had done.

At root, I was trying to hold onto the magic. Just as my mother dotted plaster with eye-liner, or added gold leaf to Athena’s bust, she was trying to conjure antiquity, to summon history somehow. She used high-quality glaze. I used gelatin. We were trying to capture some sort of magic.

Writing Medusa of the Roses, I was trying to hold onto the memory of my last minute. I felt like I was constantly asking for permission.

“You didn’t even grow up in Iran,” my mom said, as if that invalidated trying to have a relationship with the culture.

Diasporic identity was difficult to manage while writing this book. Even in my artwork, I wasn’t sure to what extent I could explore being Persian. I never had luck submitting queer Persian video art out into the world. The breakthrough came when I realized that my queerness was such an important part of my personality. The queer communities I belong to and navigate (up close and from afar) have always been more accepting than any union based on blood, birthplace, or neighborhood. Was I writing this novel to get across a portrait of Iran, or did I want to create a love letter to prickly, complicated queer love? I landed somewhere in between, writing something that feels neither reverent nor repulsed. There were so many times when it would have been easier to make something a little more exploitative of western value placements on non-western circumstances. I’ve had to stomach many teary-eyed “it must be so hard for you” pats on the back when I mention I won’t return to Iran. It’s complicated. I didn’t want to write something out of pity, so I decided to write a novel in which the lovers aren’t adamantly trying to leave their homeland. They love each other, and they want to fight to be in their home country. I don’t exactly relate to that sentiment. I will gladly leave a circumstance or a place that harbors animosity towards me. My allegiance is to my spirit, and trying to keep a part of me afloat and aflame. Did I need permission to write this book? Was my diasporic experience valid? I eventually learned that it was enough to start a conversation, a ribbon, between me and the abyss.

I was surprised by how tightly I wanted to hold onto memory. Eventually I knew I needed to loosen this affair with my last trip to Iran, for authenticity can come from the lies as well as the truth.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write in the morning fairly consistently. I go for a run in the early hours, when it’s just me, the coyotes, and skunks I’ve startled at least twice. After, I sit and write. Since I live in a studio apartment, I usually just sit on the floor of my closet typing away while my partner sleeps. A thousand words is the aim. Maybe later in the day I’ll reread the thousand words I wrote the day before, so the editor side of my brain can approach the text with a bit of distance. In tribute to my days as a young writer, as a junior-high kid with an array of gold-edged notebooks, I sometimes write by hand in a café before it gets too crowded. Those entries are a bit more intimate, searing poetic one-liners that can be truer than the quantity-based writing sessions. Writing a novel is daunting. Writing an essay can be terrifying. I try to make it interesting with variation.

I try to alternate art practices throughout the day, week, or month. I might be deeply invested in writing, but I like to switch it up by making artwork or watching films or reading art/film theory.

I can come up with unexpected imagery or quirky plot points fairly easily. Perhaps it’s because I’m a good liar. My work will likely always braid together sex, death, acid humor, mythology, and the cinematic. Still, I never want to be stuck in aesthetics and artifice. I want to have something new to say. I write daily, though it’s harder now that I know it takes roughly two years for a novel to come out. How strange that something I’ve written today for novel number seven might not be out in the world for fourteen years. But allowing that cushion of time could be miraculous. What I write today is an offering to myself in the future. I can return to the novel, the plot points, the imagery, and add the nuances from my future experiences. Same as I did with Anjir. He began his story over a decade ago, but hindsight allowed me to cut deeper into his feelings. The anxieties I felt at the time I started writing his tale are a little clearer for me now, still painful to face but important to unpack.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m always reading Sophie Calle. Her texts are triptychs: artwork, art object, and performance. The Hotel is her diary from a stint as a chambermaid, during which she photographed the belongings of the hotel guests. I’m savoring making my way through Suite vénitienne.

When I need inspiration I visit Joseph Cornell’s writing. Joseph Cornell’s Theater of the Mind: Selected Diaries, Letters, and Files is a cherished text. His shadow boxes have influenced so much of my work. Aren’t DVD menus and early webpages just digital shadow boxes? I love reading his letters. His gentle reclusiveness gives me hope when anxiety keeps me stuck in my room eating expired deli turkey slices. He ate a grotesque amount of sweets. My hero.

Tehrangeles by Porochista Khakpour is on my bedside table. (I sleep on the floor, so I guess it’s my coffee table.) Porochista has always been one of my literary lighthouses, because she makes unique, complicated, and biting work, tinged but not solely defined by Persian-ness. Her biting (and hilarious) satire of a SoCal Iranian subculture doesn’t shy away from dark comedy. I always worried writing about my ethnicity had to be woeful, corny AF passages about “maman’s tahdig.” (But for real, my mom makes a mean tahdig.) Porochista opened my eyes to how one could incorporate being Persian with humor, melancholy, and complexity.

I just got this book about death photography (Securing the Shadow: Posthumous Portraiture in America) that I’m too excited to even open. I like this stage where I’m imagining all the places it can go.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Jean Genet has always been very influential to me. He died the year I was born, so I imagined a wicked kinship (though he probably would have laughed at the mission-style strip malls of Rancho Cucamonga). There are similarities in our novels, some theft, sex, death, and perversity. Craigslist was hardly the same as cruising in Marseille, but there were through lines. I learned about simultaneity from his work. A character can be pacing in a prison cell, but also be walking through a garden. His maximalism is magnetic.

Marguerite Duras’s writing is clean, poetic, and brutal. So much is packed in her brief novels. In The Lover, the cool detachment to sex and desire felt very close to my own. Sure, some of my suitors reached out to me in late-aughts Myspace convos, but the bruise was always the same: intimately violent.

The first novel I reread multiple times was Jazz by Toni Morrison. There was a musicality to it, a melancholy noir, all set in the aftermath of a heartbreaking betrayal. A woman deals with the consequences of her husband’s affair with a young lover. The noir elements of misfortune, betrayal, and melancholy are there. From this novel, I learned how to toy with when a novel begins. Sometimes it’s long before any sign of trouble (“the garden of innocence,” to borrow from the language of the melodramatic imagination). Sometimes it’s during a moment of high action. Oh, but in Jazz, the aftermath is vibrant and telling, tumultuous and quietly untidy.

Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh introduced me to so much Persian mythology. His epic turns history into something magical. However, one passage stands out. During a slight interlude, the Ferdowsi stops telling the tales of the empire to commemorate the death of his son. I’ve learned to sew a bit of myself (or a lot of myself) into my work too, with immediacy and without fear.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Medusa of the Roses?

I recently came across the entry I wrote in a friend’s yearbook during my senior year. I didn’t sign it, but I recognized my own handwriting. It was around the time of my high school reunion, one I was intent on going to because life in a homophobic suburb circa 9/11 was a challenge. I knew the dark comedy still had some acid content to provide. Prior to the event, I sent advanced copies of my novel to a few of my old college professors as a thank you for their support in my awkward, angsty days. Most of them responded kindly. One of them had had a massive stroke, so her husband wrote on her behalf. There was a consistent thread through the messages.

Of course we remember you. We knew you were going through a lot.

At first I chalked this up to micro-homophobia, the assumption that because I was young, gay, and Persian, I must have been facing challenges. I definitely had my share of mental health issues, and the collection of meds to prove it, but I thought I was good at hiding my turmoil.

The yearbook entry I wrote for my close friend read almost like a suicide note.

I’m barely alive, almost a speck of a person, all would have been left behind, gone, erased, without your friendship.

The sentiment was there in my high school reunion, while the 360-degree selfie moment swung in circles and smacked the wooden fence of the tacky dive-bar patio.

“I know it must have been hard for you then,” one of the honors kids said while someone’s phone transmitted Jimmy Buffett to the bluetooth speaker. (I was disappointed they didn’t opt for a more appropriate mid-2000s playlist. No Usher? Inaccurate.)

It was hard for me then. It was hard for me for a long time, until I got proper help for anxiety and depression. The former classmates and professors, maybe they did see me. Maybe they saw more of me than I did.

The most surprising part of writing Medusa of the Roses was realizing how personal this work of fiction was. Revisiting that yearbook entry, I saw glimpses of Anjir.

7. What is one thing your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

I am an overly cerebral beast. I overthink to the point of physical nausea. Since I also make video art, I’ve always wondered if I should spend more time working on art, or if I should prioritize writing. Did I want to be Navid the artist, Navid the filmmaker, or Navid the novelist? For me, writing always comes first. It’s the first thing I do in the day, and it was the first (and maybe only) activity that brought encouragement from adults in my life. Even with my novels—I overthought which one I should work on, Medusa or what will be my second novel. Did I want to start with such a Persian tale and risk being pigeon-holed, or work on something wildly baroque? To me, all these texts felt different. My agent, Mariah Stovall of Trellis Literary Agency, pointed out that even though these projects seemed very different to me, they were very much works by the same creator. She made me see that I am the constant. Genre is drag.

My editor Katie Raissian (previously at Grove Atlantic, currently at Scribner) knew how antsy I was as soon as I found out it would take two years for the novel to be published. With so much anti-trans, anti-gay, and anti-drag legislature out there, I wanted my work to be in conversation with these issues immediately.

With deadpan empathy, Katie said to me: “For better or worse, these issues aren’t going anywhere.” She reminded me that I was writing something we hoped would have a life beyond the present moment, so we needed to do right by the characters. When good and ready, the novel would join the waking world. She was right. The fight is ongoing for many communities, queer and beyond, trying to go about their lives without getting killed.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Medusa of the Roses, what would you say?

My partner and I have been together for over a decade. At some point, maybe midway through our relationship, we realized something about nostalgia. We always looked back on the apartment right before, or our last jobs, or our school schedules from the not-so-distant past. “Remember Casbah Cafe? Remember when you’d pick me up from the bus stop after my Hitchcock class? Remember when you used to drive me to the cemetery for my shift?” We decided to start enjoying our specific circumstances while they were happening, instead of chasing after nostalgia. Enjoy every chapter for what it is. Whether it’s grad school malaise, or two busy work schedules that only collide for laundry and a guava-cheese pastry during the dry cycle, that was an important lesson to learn. I would grab younger Navid by the shoulders and tell him to take note. This chapter is just as scary as any other. With a novel out in the world, there are new anxieties. But even now, even in a time of personal or political worry, there are pockets of triumph.

I would also tell myself to start contemplating what success means to me. I didn’t set out to write a novel that would appeal to a large audience. I just wrote something I thought I would enjoy reading. Did I think anyone would appreciate a text with queerness, noir, Greek mythology, and Persian folklore? I truly don’t know. So now that it’s over, now that my book is on shelves and on bedside tables (I hope), is success defined by accolades? Is it book sales? Is writing something divisive the end-goal? I still don’t know. I just know I wrote something that made me feel vulnerable, a portrait of myself within circumstances that aren’t my own. Perhaps success is just finishing the work, or being quietly subversive. If I started thinking about it sooner, maybe I would have the answer by now. I don’t. But per my own advice, maybe I should enjoy the uncertainty of this chapter. Here we are. There we were.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

A visit to Marienbad. A conversation with Barbara Stanwyck. Evenings with Slowdive. The additional work I did to write my novel was all in my head. In Rancho Cucamonga, the California suburb I grew up in, the only cultural spot was the local Barnes and Noble. I learned about jazz from Mimi’s Cafe. My local art house theater was the channel Turner Classic Movies.

I watch films for many reasons. Usually I’m left with many questions. What makes one plot work versus another? Which films linger and which ones don’t? Does a tidy ending leave one with as many questions as one with a more jarring climax?

In the film Detour (Ulmer, 1945), a man’s awful luck gets him into an unbearable amount of misfortune. If he got away with his identity-theft plot, would that film have stayed in my mind for just as long? Same with unrequited love and melodrama. The “almost-but-not-quite” is what bruises. It’s a difficult concept to balance in my own work. At what point is a plot explosive versus exploitative?

Films invigorate my imagination. For example, in Medusa of the Roses, many scenes take place inside hotels. I had my own memories of dinner parties in Tehran, or visiting a holy city with my now-deceased aunt. Rewatching Alain Resnais’s Last Year in Marienbad helped give me physical details to incorporate into my work, almost like using a nude model to practice sketching. The dizzying sequences of hallways, geometric gardens, and chandeliers helped me capture place when I couldn’t. I’m a fast-moving writer, enter the scene and move on. But there were times when even in my quest for brevity, I knew I needed to give a bit more detail. (Well, my agent and editor knew I needed to linger in the moment some more.) How does one stay in an imagined room? Descriptions in screen or stage plays can be brief, because the visuals will be built out by a crew. In the case of a novel, a little more is needed. I leaned on the films that inspired me throughout my life. For example, Pépé le Moko’s tour of the Casbah helped me when I felt I had wrung all I could from my memories of the Tehran malls and bazaars. Much of Medusa is drawn from places and conversations I had during my last trip to Iran. Conjuring a whole novel from a month’s worth of experience was impossible to me. Memory was the starting point, but the set needed to be built with words.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

My mother found out I was gay from my journal when I was eighteen. I rarely wrote anything personal in there, nothing about my burgeoning sexuality, the dangerous hookups or the disappointing threesomes that didn’t pan out once they realized I was Persian. (“You looked Latino from afar,” one of the dudes said.) The first winter I was in college, I planned to go to Paris to see a grad student who had been courting me since I was seventeen. I didn’t need my parents approval to go to France, because they weren’t helping me through college in any way, and my father was in jail for white-collar crimes. Still, I decided to double down on a lie. I made faux permission slips, itineraries, and film dossiers.

“I’m going to France for a film program,” I told my mom. She hesitated to believe me, but was too depressed to fight back. Until she read three damning sentences in my journal.

My family thinks I’m going to France for a film program. I’m not. I’m going to see a boy I think I love.

I knew something was up when I got home from my double shift at a Barnes and Noble Cafe. With my apron over my shoulder, and expired Cheesecake Factory cheesecake crumbs still on my face, I heard my mom weeping.

“It’s not true,” I told her. “It’s a writing prompt I learned. Take something from your life and turn it into fiction.”

Some distorted version of that lie became my advice to myself.

I don’t really write personal journal entries to this day, not with any regularity. Instead, I sink my thoughts into my characters. An event that might have happened to me yesterday (seeing a young boy toss ice chunks at a trash can full of bees) somehow might make its way into the life of a murderous tin-type maker. I thrive in the blur between my waking world and my invented worlds. It’s a quiet way of writing a diary. Documenting a day is also admitting its end.