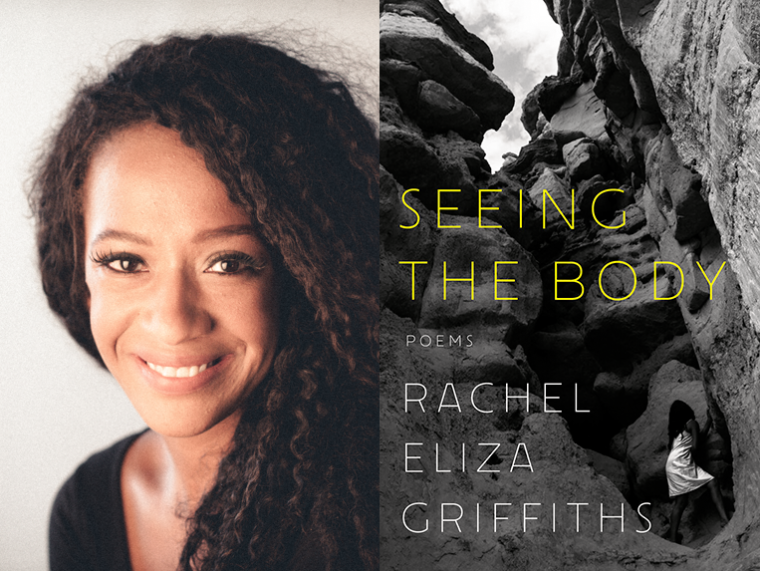

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Rachel Eliza Griffiths, whose latest book, Seeing the Body, is out today from W. W. Norton. In poems and self-portraits, Rachel Eliza Griffiths traces her grief in the wake of her mother’s death. She looks closely at her mother’s body—her hands, gestures, language—in both sickness and health, and examines, in turn, how this witnessing of illness and loss affects her own body. “I miss / the mind I had when I had / my mother,” she writes. Beginning and ending in this most intimate loss, Griffiths seeks a new way to be in the world, to continue to make art, fight injustice, and hold onto the loved ones that remain. “Radiantly elegiac, this hybrid work of poetry and photographs is one we all need for living, loving, and letting go,” writes Edwidge Danticat. Rachel Eliza Griffiths is a multimedia artist and poet. She is the author of four previous collection of poetry, including Lighting the Shadow (Four Way Books, 2015), which was a finalist for the 2015 Balcones Poetry Prize and the 2016 Phillis Wheatley Book Award. Her literary and visual works have also appeared in various publications, including the New Yorker, the Paris Review, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and Guernica. She lives in New York City.

Rachel Eliza Griffiths, author of Seeing the Body.

1. How long did it take you to write Seeing the Body?

My mother died in 2014. Maybe I began writing poems, at least fragments, during 2015. I was doing edits right up to the last moment I had to turn in the final copy. The photographs in the book were created within a similar window. That’s around six years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The uneven rhythms of grief don’t allow you to do or to feel life as you did before. Even the writer you were before is altered. It’s unquantifiable. Losing my mother forced me into the most difficult transformation of my life. Each poem drew me further into something I didn’t want to accept, which was that my mother was dead. Slowly, I understood that I also needed to put a lot of things in my life that frightened me to rest so that I could hear my own voice. It took some time for me to say that these poems were becoming a book. I didn’t want to say it.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I make things every day. I write. I work with visual material. Reading is my writing too. Deadlines are my frenemies. Given the current world, so much drains me, but making anything, even dinner, helps. Lately, I find myself needing to rest in ways I didn’t before. Writing is restorative, yes, but it’s taking so much more to get the engine into the air.

4. What are you reading right now?

The Complete Stories by Clarice Lispector, Jack Whitten’s Notes From the Woodshed, Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane, Joy Harjo’s How We Became Human, Gwendolyn Brooks’s Maud Martha, and some essays about Joan Mitchell. I keep returning to Virginia Woolf’s diaries. Also, I’m diving into Melville’s Moby Dick again for a project.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I want everyone to read Ama Codjoe’s poetry. Read Blood of the Air (Northwestern University Press). She’s divine. Read Rio Cortez’s I have learned to define a field as a space between mountains (Jai-Alai Books). Read Aldrin Valdez’s ESL or You Weren’t Here (Nightboat Books). Authors published by Archipelago Press or Alice James Books have my attention.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Trying to do too much at one time. I can hold a constellation of cross-genre projects simultaneously, and work on all of them, but sometimes there are moments when I really must concentrate on one thing. If I don’t then I end up sacrificing the quality of everything. There’s a rhythm to saying Yes and No, whether to myself, or to others, so that I can actually work.

7. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I’d ask writers who want an MFA what they think they want from it and how they came to that thinking. But I wouldn’t recommend one thing to all writers because we all need different things. No matter how you’ve come to writing, you are aware you have no idea how any of it will turn out. Except, of course, that you must write—and read.

Especially right now, many writers can’t afford to go into debt for an MFA—speaking as someone who is still paying for mine—when there are so many resources that can be curated to have community, support, and feedback. There are marvelous MFA programs that will support you. Find them.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Seeing the Body, what would you say?

Be careful with your sadness. I don’t want you to die.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

My most trusted reader of my work is myself. After myself, it’s my agent, Jin Auh of the Wylie Agency. Once I’ve gotten the work to a certain point I know she’ll give it her full attention. Her questions help me think and feel through my language and my ideas. Her voice complements my intuition. And she is always truthful, on behalf of what the work wants and needs for its own sake.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

My friend, the incredible and generous poet, Willie Perdomo, once told me to work on my writing in pieces, breaking it down, and do a bit each day. I needed his wisdom. Because I can get overwhelmed. Left to my anxiety, I’ll ambush myself before I even begin because I think I have to know the entire life of a story and that it must be a single breath. But that’s not how we breathe.