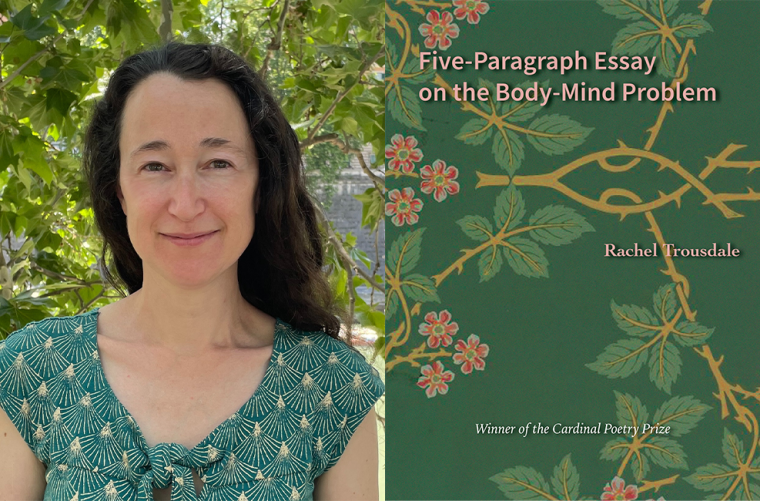

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Rachel Trousdale, whose debut poetry collection, Five-Paragraph Essay on the Body-Mind Problem, is out today from Wesleyan University Press. The collection explores how the interplay between the mind and body illuminates our most vital relationships—with other people, wild spaces, and works of art. In both free verse and invented forms, Trousdale examines the intensity and challenge of romantic love, the chaotic joys of parenthood, illness and grief, and the way we develop a sense of responsibility to the world around us. Robert Pinsky, who selected the manuscript as winner of the inaugural Cardinal Poetry Prize, said, “A rare gift in art is directness: to turn a clear, unsentimental gaze on love and grief in all their variations, with no smokey or mysterioso evasions. Almost as valuable is meaningful surprise, the stunned laughter of recognition even if the subject for marvel is loss. The heartfelt, unpredictable poems of Rachel Trousdale attain that kind of discovery.” Rachel Trousdale is a professor of English at Framingham State University. Her poems have appeared in the Nation, the Yale Review, Diagram, and other journals, as well as in a chapbook, Antiphonal Fugue for Marx Brothers, Elephant, and Slide Trombone (Fishing Line Press, 2015). Her scholarly work includes Humor, Empathy, and Community in Twentieth-Century American Poetry (Oxford University Press, 2021) and Nabokov, Rushdie, and the Transnational Imagination (Macmillan, 2010).

Rachel Trousdale, author of Five-Paragraph Essay on the Body-Mind Problem. (Credit: Nick Beauchamp)

1. How long did it take you to write Five-Paragraph Essay on the Body-Mind Problem?

The oldest poems in the book are probably fifteen years old, but I figured out what shape I wanted the book to take about ten years ago. At that point I had a full-length manuscript, but many of the poems in it were placeholders, so the revision process consisted of slowly writing new poems better suited to the structure I had in mind. I am still fond of some of the poems I took out, but they didn’t belong in this book.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Understanding who I was talking to. I’ve written a couple books of criticism, but those have a very targeted audience—I knew exactly who I was writing for. It took me a long time to imagine who might want to read a book of my poetry. Then I changed tacks and decided that I should write a book that I wanted to read, and hope that people would want to read it too.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write crankily, in stolen moments. Dictating into my phone while I drive to work and then revising from the garbled transcription in the ten minutes before class starts. Hunched over my laptop on the couch when I should be grading papers. Hiding in my room when my kids want to play. It’s lucky that I work in a short form, because during the school year I get very little writing time. But on the other hand, all the things that keep me from writing give me stuff to write about, and often I’m doing the composition in my head when an outside observer might think I am doing something else entirely.

4. What are you reading right now?

The books I have in progress are Stephanie Burt’s Super Gay Poems (Belknap Press, 2025), part two of Emil Ferris’s My Favorite Thing Is Monsters (Fantagraphics, 2024) and my class prep, William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience (1794). They make a lovely E-minor chord.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Harryette Mullen! She does get recognition, but she deserves more. I want to grab people by the arm like the Ancient Mariner and read her at them.

6. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

The title poem riffs on the five-paragraph essay, and I wanted the book to parody that structure: A brief intro stating themes, three sections developing those themes, and then a conclusion. In a classic five-paragraph essay, this involves a lot of very dull repetition. But because the book is, in part, about the way things escape or defy or exceed their containers, the sections keep leaking into each other, and instead of reiterating the same ideas, the conclusion expands them, or turns them inside out. At least, I hope that’s what happens!

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

At the start of the pandemic, my friend Catherine Rockwood sent an e-mail to several of us saying, “We’re going to need poetry to get through this.” We formed an online writing collective which we called the Harpies, giving each other feedback and writing prompts and moral support. It was sanity-saving. And what was so important was not just the word “poetry” but the word “we”; poetry is community, writing is shared.

But you’re asking about editors in the more formal sense. Wesleyan University Press has been a delight to work with throughout, but a moment that stuck with me was in the first Zoom call I had with [the director and editor in chief of Wesleyan University Press] Suzanna Tamminen. I said something like, “I think I want to cut my poem about wildfires and replace it with something else,” and she responded with the poem’s actual title: “You mean ‘How to Survive a Wildfire’”? And suddenly I understood that someone whose taste and judgment I really respect was paying meaningful attention to my work. It was such a gift! (I didn’t end up cutting the poem.)

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Five-Paragraph Essay on the Body-Mind Problem, what would you say?

I don’t know if I’d say anything about the book! I enjoyed writing these poems a lot, and part of the fun was a feeling of freedom—I was playing, trying to make something I liked, something no one else had already made for me. If I told my past self this collection was actually going to be published, she might start taking it too seriously. But I might tell my pre-pandemic self to lay in a bigger supply of hot sauce.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Five-Paragraph Essay on the Body-Mind Problem?

Teaching, definitely. My students are always giving me new ideas, while also sending me back to first principles. And while, despite the title, Five-Paragraph Essay isn’t scholarly at all, my scholarship fed it, particularly my recent work on humor. Looking at the ways Elizabeth Bishop and Marianne Moore and W. H. Auden use gleams of the comic in otherwise serious poems taught me a lot about how poems can produce multivalent emotional effects. But most, being a parent. A kid can spot a lie or a partial answer at fifty paces, or at least mine can, so you constantly have to figure out what you mean and the limits of what you know. And they won’t let you get away with too much seriousness. They’ve been training me in a weird blend of improv and existentialism for ten years now, and these poems would be much less interesting without them.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Years ago, at Bread Loaf, I got to do a workshop with Terrance Hayes. He said—not just to me, to several of us—that he wanted to see “more wildness” in our poems. And I thought, yes, that’s what poems need. Not chaos; the wild has its own order. But poems want words and ideas and images that operate on their own terms, rather than being tamed to someone else’s needs. I’ve been trying for that ever since.