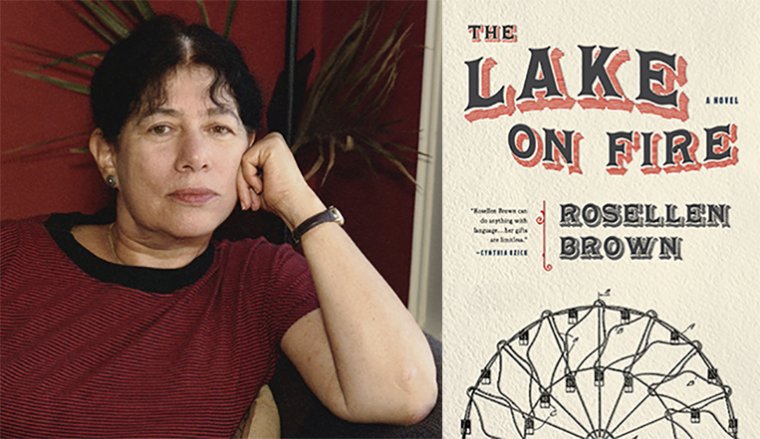

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Rosellen Brown, whose eleventh book, The Lake on Fire, is out today from Sarabande Books. The novel is an epic family narrative that begins among nineteenth-century Jewish immigrants on a failing Wisconsin farm and follows the young protagonist, Chaya, and her brother Asher, who flee to industrialized Chicago with the hopes of finding a better life. Instead, they find themselves confronted with the extravagance of the World’s Fair, during which they depend on factory work and pickpocketing to survive. The Lake on Fire is a “keen examination of social class, family, love, and revolution in a historical time marked by a tumultuous social landscape.” Rosellen Brown is the author of the novels Civil Wars, Half a Heart, Tender Mercies, Before and After, and six other previous books. Her stories have appeared in O. Henry Prize Stories, Best American Short Stories , and Best Short Stories of the Century. She lives in Chicago, where she teaches in the MFA program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Rosellen Brown, author of The Lake on Fire.

1. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Where depends almost entirely on the shifting light in my apartment that, most marvelously, sits sixteen stories up and a couple of blocks from constantly-changing Lake Michigan. So I follow the sun around and sit wherever it’s brightest (often with my cat on my lap). I sometimes wonder if I’d focus better if I had one desk, one room of my own, but I’m light-thirsty and this seems to work out pretty well. As for the “how often,” when my kids were little and I had to take advantage of every minute they were in school, I’ll admit I was a lot more disciplined; I published three books in three years. Like my waistline, I’m afraid things have slackened a little, but I still try to work every day that I’m not teaching and feel like I’m cheating when I don’t at least try, or on a dry day default to reading. It’s interesting that many people worry that reading while they’re writing might influence their work. On the contrary, I’ve always read just enough (of just about anything good) until I find myself thinking, hungrily, “I want to do that!” Then I put the book or the story away and get down to it, energized by envy.

2. Where did you first get published?

This is crazy to remember: The New York Times used to—I’m talking about the fifties—publish poetry, mostly pretty bad, on their editorial page and while I was in high school I sent them, and had accepted, a sonnet on the ghost of Thomas Wolfe. (I’m not talking about Tom Wolfe but the Thomas of Look Homeward, Angel: “Oh, lost and by the wind-grieved ghost...” and so on. A book not to be read when you’re older than sixteen.) In college, I had a few poems in little magazines and one in Mademoiselle and then my coup, never to be repeated: Poetry Magazine took a sestina of mine and published it in my senior year. A sestina is always a sort of tour de force; maybe if I tried that again, they’d take another poem! As for my fiction, I didn’t start writing that until later, moving gradually from poetry to prose poetry to some pretty unconventional fiction because I didn’t really know (or care about) “the rules.”

3. How long did it take you to write The Lake On Fire?

Oh, what a question! I just discovered, via an old letter that I happened upon, that I had begun talking about what became this book as long ago as 1987! I’m horrified. I published four books between that early hint of curiosity and my actually writing and revising it, so I was obviously not sidelined by that early—I’ll call it an itch. Somewhere along the way I wrote a first version that was set in New Hampshire. Of course, Chicago is at the center of the published novel. I could write a lot more than I have room for here about how long it takes me—and, I suspect, most writers—the coming together of two impulses to ignite a story, and that’s what happened when I moved here and learned so much about the city’s history. I sort of (but only sort of) wish I could find the original manuscript that never took fire but I have no idea what happened to it. (Good metaphor, given the name of the final book.)

4. What was the most surprising thing about the publication process?

How wonderfully attentive an independent (read: small but not powerless) press could be, if it’s seriously well-run. I got an almost instant response from Sarah Gorham, whose Sarabande has always been one of my favorites—none of that hanging around the (virtual) mailbox waiting for somebody in New York to say yea or nay because, I trust, she didn't have to run things past an army of marketers and others before she could say “I love it!” And their marketing has been another surprise: Really attentive and responsive, Joanna Englert is all in, efficient, and enthusiastic. Though I had a good experience at Farrar, Straus and Giroux with their publicity and marketing for my book Before and After, this is far more personal and agile.

5. What trait do you most value in an editor?

Respect for my intentions and an absence of the need to prevail. A good ear, not always available even from editors who can talk about structure or motivation and so on but who can’t hear a rhythmically perfect (or imperfect) line. I’ve had two great editors: The first, John Glusman, was just starting his family when I worked with him on Before and After, which raises some hard questions about parental responsibility, and he was deeply attuned to what I was trying to do. And my current editor, Sarah Gorham, is herself a terrific poet and essayist who knows how to listen to the rhythm of my writing, which—as someone who herself began as a poet—I take very seriously.

6. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

I’m hardly alone in saying that—both understandably and unforgivably—the “legacy” publishers look at their numbers, past and projected, far more attentively than I think they consider the quality of books they deem marginal. They are, like their counterparts in the entertainment industry, more sheeplike than daring.

7. Who is the most underrated author, in your opinion?

Not under-rated—he gets great reviews and sometimes wins prizes—but I find too few people who know Charles Baxter’s stories and novels. I’m not sure why: Too quiet, maybe? Never brings down the house but writes with exquisite sensitivity and great good humor, with his passion for social justice sometimes stage center, sometimes lurking around the edges. I remember him saying, memorably and better than this, that what we need to do is make people less certain about their certainties.

8. If you were stuck on a desert island, which book would you want with you?

This is still a little too much like the “who are your favorite writers?” kind of question. I hate ranking writers because it’s so apples and oranges. Two of my favorite novels, for example, are William Maxwell’s So Long, See You Tomorrow and Evan Connell’s Mrs. Bridge. But then, what about Alice Munro’s The Beggar Maid, which I consider one of the most satisfying collections of (connected) stories I know? To the Lighthouse? And then, on another day, trying keep dry the suitcase I’d have rescued from whatever boat capsized and deposited me on that island, where do I put Max Frisch’s Man in the Holocene or Marilynn Robinson’s Houskeeping, novels so different you might want to find another name for their genres? And then there’s poetry. And then there’s nonfiction, at least half the entries in The Art of the Personal Essay. So many delights! How to choose? I refuse.

9. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

I’m a plodding, one-idea-at-a-time writer, unlike some of my friends, who are filled to overflowing with great projects jostling each other to be attended to. Then again, with eleven books behind me, I guess I shouldn’t complain. Entertainment Weekly, of all places, recently chose The Lake on Fire as one of their “20 Fall Books Not To Be Missed,” and they called me some very complimentary things, but it was kind of a backhanded compliment because they said people ought to get to know my name because I’d been flying under the radar. Then again, whoever compiled the list was probably in first grade (if that) when my last book came out so I guess that’s on me!

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

The only teacher with whom I ever took a fiction class, a fine and much undernoticed writer named George P. Elliott cautioned us, at a time when we young ‘uns were too easily snarky and judgmental, to be compassionate toward our characters. He cited a letter by Chekhov in which Chekhov suggested that, at most, we should admonish people whom we find wanting: “Look how you live, my friends. What a pity to live that way.” Hard to live up to and I fail often because cleverness is so much easier to reach for than sympathy, but I try to remember and, without too many compromises, act upon it.