This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Sarah Thankam Mathews, whose debut novel, All This Could Be Different, is out today from Viking. In this coming-of-age tale set during the Great Recession, recent college graduate and Indian immigrant Sneha thinks she has “been saved from drowning” when she lands a position as a corporate consultant in Milwaukee. While the poor economy has forced many of her friends to move home with their families, Sneha has no such safety net: Her parents have returned to India after a period of difficulty in the United States, leaving Sneha to fend for herself. While her new job isn’t perfect—particularly its lack of health insurance—Sneha feels optimistic as she bonds with an old friend, makes new ones, and falls in love with Marina, a dancer. But when her career takes a turn for the worse and other challenges emerge, Sneha and her comrades find themselves in dire straits and reliant on a friend’s bold plan to dig them out of trouble. Kirkus Reviews praises All This Could Be Different as “marvelously envisioned. Resplendent with intelligence, wit, and feeling.” Sarah Thankam Mathews grew up between Oman and India, immigrating to the United States at seventeen. Her work has been published in The Best American Short Stories 2020, and she is a recipient of fellowships from the Asian American Writers’ Workshop and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. In 2020 she founded the mutual-aid group Bed-Stuy Strong.

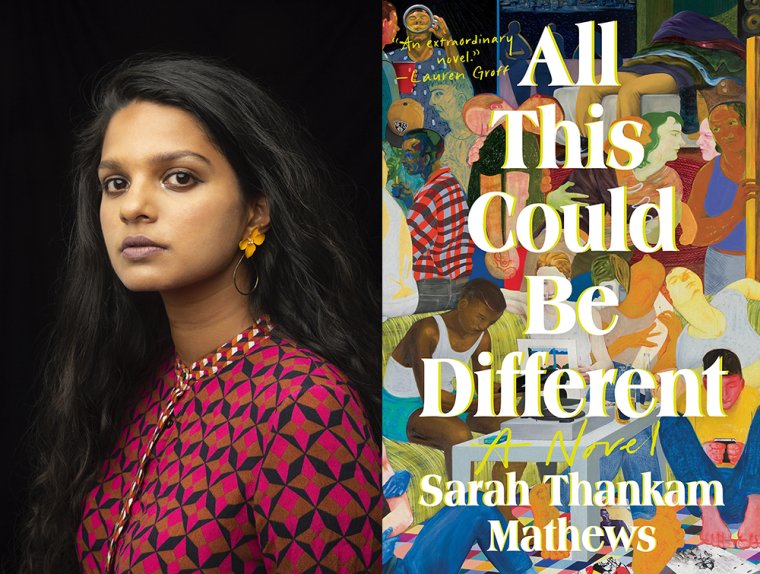

Sarah Thankam Mathews, author of All This Could Be Different. (Credit: Dondre Stuetley)

1. How long did it take you to write All This Could Be Different?

I wrote All This Could Be Different in a fever dream, mostly during the summer and fall of 2020, after working for seven years on a completely different project, after having written nearly eight hundred pages of an attempt at it. I felt determined to put every lesson of failure from that previous project to use when writing All This Could Be Different, which felt in many ways like my second round in the ring.

All This Could Be Different grew out of what I thought would be a short story titled “Milwaukee,” which I had first pictured as a satire of the modern office combined with a disaffected queer romance. But upon rereading it I thought, “Well, this isn’t a short story. But there’s something alive here.” The voice that emerged on the page—preoccupied with these big questions around love and material needs and coming of age—felt large enough to hold a novel.

It feels as true to say that I wrote All This Could Be Different in four to five months in 2020, when I had unemployment benefits, as to say that the process of being able to write it took at least eight years, if not longer.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

First: setting clear intentions and formal constraints, instead of trying to write a book that bloated itself through trying to be everything in the world. Second: maintaining my confidence that I could execute my intentions. Writing, I now believe, is both a confidence trick and an alchemical process: The prose itself radiates what the writer is feeling while writing, from introspection to fury to cool certainty. You can tell when a writer is having a good time writing. With All This Could Be Different, I had tapped into a vein of confidence, for once knowing exactly what I wanted to do and say.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

For years I wrote at night, after my day job. After I went to graduate school for writing, I tried to write every day and mostly succeeded, dutifully parking my proverbial butt in the proverbial chair. But in 2020 I started writing when I felt like it. I make work in booms and busts. I don’t force myself to write and try to have a more intuitive, less rigid practice.

4. What are you reading right now?

Self-Portrait With Ghost by the great Meng Jin, and I’m rereading Gold Diggers by the brilliant Sanjena Sathian. Oh, and a book of poems, Spooks, by Stella Wong.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Toni Morrison and Arundhati Roy are the reason I am a writer. Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy gave me the key that unlocked All This Could Be Different. Other varied influences: June Jordan, Annie Proulx, William Maxwell, T. S. Eliot, Deepak Unnikrishnan, Ben Lerner, Perumal Murugan, Danez Smith, Marguerite Duras, Dionne Brand, Edward St. Aubyn, Sayaka Murata, Saul Bellow, Zadie Smith, Michael Cunningham, Claire Messud, Anuk Arudpragasam, and Vikram Seth.

6. What have you learned about the publishing industry that you wish you’d known before you published this book?

There’s something irreducible about this experience, and it will come much slower than you first wish it to; then it will come all at once. There’s making art and there’s moving that art out into the world as a commodity—an arguably decently democratized and accessible commodity—and those are two different things.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

That it takes a long time and many people to publish a book well. That I wasn’t an employee but a creative partner in publishing the work, and what I wanted mattered.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started All This Could Be Different, what would you say?

There’s the work you do, and there’s the person you are. Both matter, but they are not and never will be the same. What’s for you will come to you. Be patient and play the long game. The people who love you most will be proud of you when you write the book but will also love you if you never write the book. Drink more water and take care of your lower back, bitch.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Many years of various day jobs and freelance jobs. The emotional work of choosing to be the caretaker of my creative life and continuing to believe in it without much evidence that I should.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

From my friend C Pam Zhang, who in addition to being a truly remarkable writer has been an incredible possibility-model for me as a slightly younger-in-career author: “Walking is writing. Crying is writing. Talking to a parent whose health you fear for is writing. Cooking is writing. Lying prostrate on the rug and watching sun stripe the wall is writing. Your lover’s hand on yours is writing. Your dog is writing. I have had years in which I could not see the shape of my life or string together a good sentence; and I have had a summer in which, three years late, the fog lifted in a different climate and suddenly I could write about my father. Don’t force the words. They will come, like old friends. ... If you are grieving, then I give you permission to write in the best way you can—which is to say, to live.”