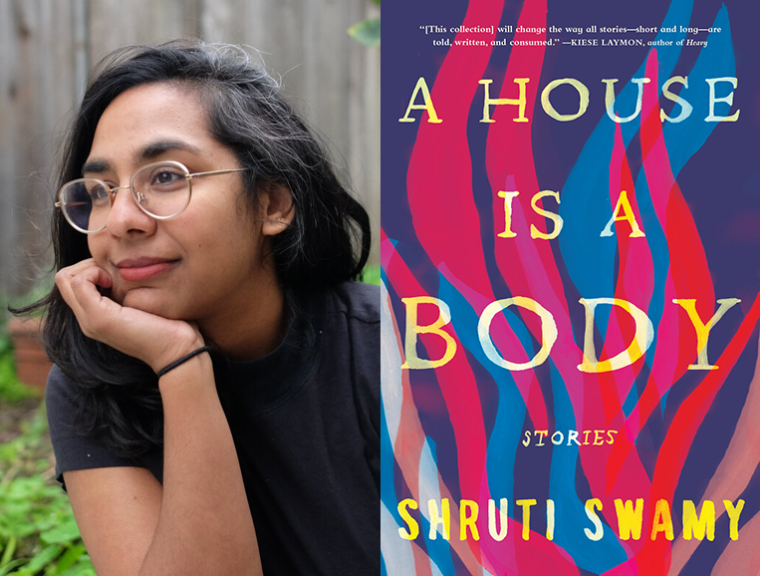

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Shruti Swamy, whose debut story collection, A House Is a Body, is out today from Algonquin Books. Set in the United States and India, A House Is a Body features a diverse cast of characters who are struggling to make their way in the world amid mental health crises, loss of loved ones, and extreme wildfires. In one story, a woman repairs a burst seam on a coat that belongs to a dead friend, “Why bother?” she wonders. “But she must bother.” Later, she observes, “What a violence mending does, the needle piercing and piercing.” A House Is a Body is filled with such tender yet sharp observation. The characters always “bother”; their actions brim with humanity even as the world moves to take it away. “There is nothing, no emotion, nor tiny morsel of memory, no touch, that this book does not take seriously,” writes Kiese Laymon. “Yet, A House Is a Body might be the most fun I’ve ever had in a short story collection.” Shruti Swamy’s writing can be found in the Paris Review, Prairie Schooner, and the Kenyon Review Online, among other publications. A Kundiman fellow, she has also been awarded residences at the Millay Colony for the Arts, Blue Mountain Center, and Hedgebrook. She lives in San Francisco.

Shruti Swamy, author of A House Is a Body.

1. How long did it take you to write A House Is a Body?

I wrote a draft of the earliest story in the collection in 2008. The bulk of the book was finished by 2015, but I worked on the manuscript again with my agent in 2016, and then again with my editor last year. So I think it’s fair to say ten years—give or take.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Story to story, I had many moments of challenge—often related to plot, which is not my strong suit, or simply keeping up the momentum and courage to push through to the end. But as a whole, one of the challenges I faced was making the stories I wrote into a cohesive collection, one that was not bound by location, shared characters, or even a single common theme, but rather a voice, perspective, and sensibility. I guess what I mean is the challenge was finding the larger picture, how the stories spoke to each other, and what they were trying to say. It changed quite a bit over the years—often it was the help of an outside perspective that allowed me see what I was trying to do and to shape the collection accordingly.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

In the corner of my bedroom I have a very, very small desk that was actually called a side-table in its Craigslist posting, upon which I did very little writing before the pandemic. I use it much more now. With noise-cancelling headphones on, I try to imagine I’m shutting a door to the outside world, though the headphones don’t really cancel much noise. I try to reserve the afternoon hours while my daughter is napping for my writing, but I am generous with my definition of “writing”: reading, writing in my journal, and meditating—but not napping!—all count. I completed a major revision of my novel during the first month of the pandemic this way, running on the world-ending adrenaline of it, maybe. Now I am not as focused. But I have been through fallow periods before so many times that they don’t worry me so much. Something will come again, if I am listening.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just finished Renee Gladman’s Houses of Ravicka, the conclusion, I think, to her dreamlike and disorienting series of novels that center on the invented city-state of Ravicka. I wouldn’t like to live in Ravicka, whose customs and language are so obscure and subtle to outsiders that they are close to nonsense. Still, inhabiting it for a time was an escape for me from the surreal nonsense of our current reality. Also, with the rest of America, I am reading Brit Bennett’s riveting The Vanishing Half. What can one say about it, except that it is a perfect novel.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Ambai, who writes in Tamil, but is readily available in translation in English. I’m still in shock that I learned of her work so late, with the publication of the excellent A Kitchen in the Corner of the House by Archipelago Books last year. Each story in that collection is a marvel, communicating so much about human nature—grace, violence, humor, connection, and distance—through the smallest moments.

Another author is Vandana Singh, a science fiction writer of short stories. The Woman Who Thought She Was a Planet was excellent, but her more recent Ambiguity Machines is even better. She’s a worthy heir to Ursula K. Le Guin, whom she studied with. Her ability to imagine other worlds and ways of being is astonishing, and her stories are rendered in graceful prose.

By some lucky coincidence I wound up reading both of these authors at once and felt like my understanding of short fiction—especially fiction by and about the South Asian diaspora—beginning to crack open.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I think it depends on what they wanted to get out of it. The most valuable thing I got out of it was the introduction to the books that shaped me as a writer and as a person. More than anything, I learned how to read: deeply and carefully and slowly, which is not my natural mode. I still don’t know if good writing can really be taught or learned in the classroom, perhaps not directly. But learning to read well, and also being a kind of editor for the works in progress of peers, can be enormously useful in one’s own writing life. I don’t think that an MFA is the only place to learn those things, though, and there are a lot of other means to becoming a good writer.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Rather than any one thing: After years of feeling very outside the publishing industry, it was tremendously moving and inspiring to me to have two people I admired so invested in my work. In a funny way, I think that it has made me bolder as a writer.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started A House Is a Body, what would you say?

I don’t know if I have any knowledge that will help that younger me! I had a strange sense of belief in myself in those days, which I didn’t yet deserve—my writing didn’t yet deserve it, because nearly all of it wasn’t any good. Somehow, after years and years of work, it got better—maybe I simply believed that it could, that I loved writing and I could get better at it. If I had known just how long it would take to get a book into print, I might have despaired, but now, having waited and worked through those years, I’m glad for it, in that I know that this is the best this book could be without becoming a whole new book. Because I had written so many stories by the time I sold the manuscript, I had some freedom in putting the collection together. Ultimately, there isn’t a story in the collection I don’t feel proud of, even though they were written by a younger, wilder writer who had fewer tools and less life experience at her disposal.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I am lucky to count many good and generous writers as my friends, who have read so many versions of my stories and novel. But most of all is Meng Jin, whose beautiful first novel, Little Gods, came out earlier this year. Meng has not only a great eye at the sentence level but also a kind of genius for structure—she’s able to see things buried in the text that I didn’t even notice were in there and help me tease them out. Over the years of our friendship I think we’ve come closer and closer in our taste as readers, and though our writing is different, it also seems to be interested in similar ideas and ways of seeing.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Shamala Gallagher, the poet, essayist, and also my brilliant best friend, once told me, regarding a piece of dialogue that wasn’t working: “I think your characters understand each other too well.” People misunderstand each other more often than they understand each other, and for all sorts of reasons—they miss each other’s subtext or don’t have enough context or are lying to themselves or are being lied to. And actually that can be true of the internal experience of the character as well—we often say or do things without a perfect understanding of why we did them. We’re lying to ourselves, maybe, we’re overwhelmed with emotion, we have hidden motives that lie underneath our explicit desires. People understanding each other too clearly can also be, for me, a symptom of me trying to control the story too much, an attempt to “get to the point,” which comes at the expense of actually listening to my characters.