This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Simon Van Booy, whose fourth story collection, The Sadness of Beautiful Things, is out today from Penguin Books. Over the past decade, Van Booy has been collecting stories in the form of anecdotes told to him by strangers. In The Sadness of Beautiful Things he transforms these anecdotes into fictional stories featuring muggers, musicians, hitchhikers, and other intriguing characters in a haunting exploration of the darkness of human longing, suffering, and grief. Van Booy is the author of nine books of fiction and three anthologies of philosophy. He has written for the New York Times, the Financial Times, the Irish Times, NPR, and the BBC. He lives in New York with his wife and daughter.

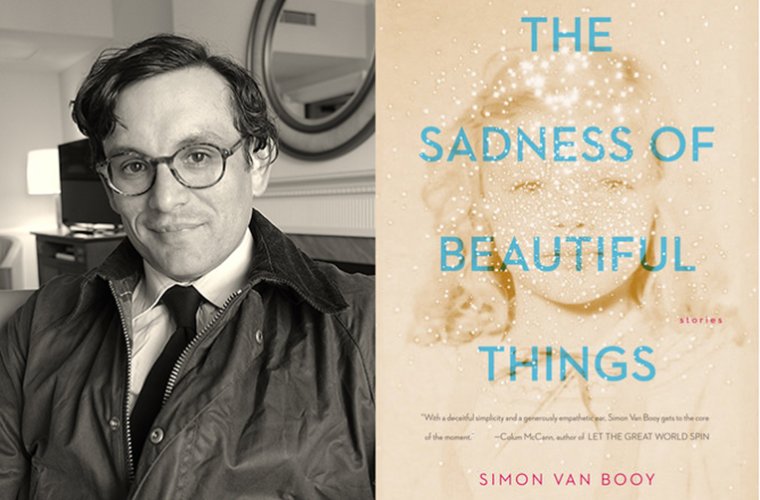

Simon Van Booy, author of The Sadness of Beautiful Things. (Credit: Ken Browar)

1. Where, when, and how often do you write?

When I lived alone in my twenties, I had a very specific desk (a plank of wood on sawhorses), chair (green, 1960s, faux-leather) and enormous amounts of time to work. Since becoming a father and husband however, I’ve morphed into more of a literary opportunist. One of my favorite directors, Andrei Tarkovsky, said something like, “the artist never creates under ideal conditions,” which I’ve certainly found to be true. Nowadays, I wake up at 5AM, run, lift weights, make my daughter’s breakfast, pack my own breakfast and lunch into Thermos flasks, drive her to school, then go to Adelphi University Library, where I have a favorite spot on C Level to write children’s fiction, and a quiet place on 5S to write adult fiction. I write from 8:30AM until the cup runs dry...usually 10:30AM to noon. If I’m having trouble, I get books of my favorite writers and put them on the desk for inspiration and support. And I always, always listen to music. Mostly early, religious music from France or Italy, or modern composers like Arvo Pärt. If I can do this for three or four days a week, it’s enough time to write two books a year. I write quickly, and intensely—on the edge of my seat, with the Internet off, sweating, crying, laughing—in other words, complete immersion. At the end of a writing period, it feels like I’ve been sitting there for five minutes. When I’m editing or under pressure, I sometimes take a Saturday and work a ten-hour stint. But that’s not the most pleasant way to work, it’s frankly awful. I don’t write every day, but I do read (or listen to part of an audiobook) every day to strengthen the roots of my practice.

2. How long did it take you to write The Sadness of Beautiful Things?

With the exception of the longest piece in the collection, “Not Dying,” I wrote a draft of each story in one sitting, so as to seal in the emotion and tone at both ends. I worked on the book while writing a children’s novel, Gertie Milk & the Keeper of Lost Things. It took just under a year. “Not Dying” was the hardest story, because it was only going to work as a very spare, almost stark piece of writing. I even had to spend the weekend in a creepy, 18th century house upstate. If you’ve read the story you’ll understand why I had to stay awake all night, and obviously not tell my wife and daughter why. “The Pigeon” was written in about ninety minutes, as I already had the structure and characters fully formed in my head after reading the real story in a New York City newspaper.

3. What was the most surprising thing about the publication process?

Honestly there was nothing surprising. My agent submitted it, an offer was made, then began the editorial process, which was fairly normal. I must say though, that having a good publicist is key these days, and I feel I have an excellent one in Chris Smith at Penguin for this book.

4. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Yes and no. I would recommend it if you already have a solid writing practice and questions that only more experienced authors can help with. I enjoyed my MFA course immensely, learning as much from my peers as my teachers. I have to say though, that I needed confidence then as much as technical instruction, and reading guidance. Thankfully the acclaimed novelist India Ganesan was one of my professors. Kaylie Jones and Roger Rosenblatt were excellent too, but Indira was more similar to me in style and tone, so she really helped coax out my writing voice. My other mentor was the late Barbara Wersba. She taught me everything she knew—much of which came from her associations with Dylan Thomas and Carson McCullers—who she nursed in extremis. Since Barbara’s slow decline into mental illness and death this year, I’ve been without a writing mentor, and of course, a friend. I think more experienced writers would gain an enormous amount of satisfaction from tutoring younger writers. It’s why I enjoy teaching so much (I work with private clients), and why I decided recently that teaching in an MFA program might be a nice fit one day soon.

5. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading every single piece of fiction I can by an Irish author called Billy O’Callaghan. He has books forthcoming with Harper, and a story called “A Death in the Family” which I believe is forthcoming in Ploughshares. I think he’s going to be one of the greats. He lives in Ireland on potatoes, cabbage, and Guinness. I’m also reading the ghost stories of M. R. James, Love for Lydia by H. E. Bates, and (I’m just looking on my nightstand) the complete poems of Philip Larkin, along with SPQR by Mary Beard.

6. Who is the most underrated author, in your opinion?

Caradog Pritchard and Michel Del Castillo. Monsieur Del Castillo is alive, and his books are available in French, but he's very hard to find in this country in English, and when I wrote to him through his French publisher, they returned my letter! I also want to say that the Turkish film director, Reha Erdem is worth exploring.

7. Where did you first get published?

My first poem was published by a vanity press in 1994. The deal was, they would publish the poem if I agreed to buy twenty copies of the anthology. I think I bought forty, though where they are now I don’t know. Even though I knew it was a scheme of sorts, I was thrilled to see my work in print. My next publication came in 2000, with a short story “The Reappearance of Strawberries” in the East Hampton Star.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Probably not reading enough. It really does provide vital nourishment, and most importantly, inspiration. But I also find the business of being a writer a little distracting.

9. What trait do you most value in your editor?

Friendliness and generosity. Where possible I’d like to be friends with my editors, and work with them for decades, through the highs and lows. This seems to happen less and less now, because editors move around more, and I think editors are working with more authors than they did in the 1950s and 1960s, and have the pressure of making numbers. But I’m fairly old-fashioned in that I value long lunches, walks in the park, fishing trips, et cetera. Good books come about from a collaborative effort—it’s almost a crime that it’s just the author’s name on the cover. Also, I would like to see more power in the hands of our brilliant editors, and I’d like to see them take more chances on strange new voices—otherwise how will we ever find the next James Joyce or Janet Frame?

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Write the book you’ve always wanted to read. Also, when you’re writing, get out of the way and let the story reveal itself to you.