This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Srikanth Reddy, whose nonfiction book, The Unsignificant: Three Talks on Poetry and Pictures, is out today from Wave Books. The collection explores a history of poetry, from Homer to Gertrude Stein to Ronald Johnson, refracted through images such as Bruegel’s Landscape With the Fall of Icarus, Hermann Rorschach’s inkblots, and Galileo’s drawings of the moon. Ranging from pictorial backgrounds in visual art to portraiture and similes to the poetics of wonder, The Unsignificant leads readers on a wandering tour of Western poetry from the ancient world to present day. The edited lectures are drawn from talks Reddy gave as part of the Bailey Wright Lecture Series in 2015. Srikanth Reddy is a professor at the University of Chicago, where he teaches classes on parody, obscenity, and contemporary literary publishing. His latest book of poetry, Underworld Lit (Wave Books, 2020), was a finalist for the Griffin International Poetry Prize, the T.S. Eliot Four Quartets Prize, and a 2020 TLS Book of the Year. A recipient of fellowships from the Creative Capital Foundation, the Guggenheim Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts, Reddy is the poetry editor of the Paris Review. With Rosa Alcalá, Douglas Kearney, and Katie Peterson he edits the Phoenix Poets series at the University of Chicago Press.

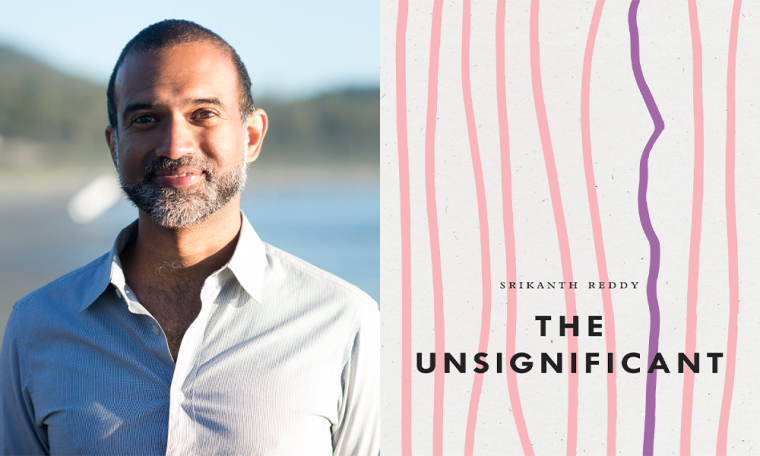

Srikanth Reddy, author of The Unsignificant. (Credit: Kaitlyn Shea)

1. How long did it take you to write The Unsignificant?

It took me about a year to write the three lectures on poetry in The Unsignificant. I had a sabbatical from teaching in the 2014–15 academic year, so I wrote the first talk (on backgrounds) over the summer; the second talk (on wonder) that fall; and the third talk (on similes) that spring. Nothing really connected those talks, beyond my fascination with the interplay between certain poems and paintings. I just dove into the dynamics of that material and let it take me where it wanted to go.

In many ways the lecture, as a genre, felt very different from writing essays or articles about poetry. With lectures you’re addressing a plural “you”—not a solitary reader, but an audience of listeners. It’s more interactive—even though you’re alone in your office while you’re writing it, you have to imagine yourself performing the talk in some fictive venue. There’s an intimacy to the lecture genre, too, because you’re writing as if you were sharing the same space with your listener, rather than some far-off reader. The orality and intimacy of the lecture bring it closer to some aspects of lyric poetry than the nonfiction essay.

Unlike a book of essays I didn’t publish the lectures once they were written. First I traveled around “delivering” the lectures to different kinds of audiences in the fall of 2015—everywhere from the Library of Congress to the Poetry Foundation to the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa—thanks to the generosity of the Bagley Wright lecture series at Wave Books. I learned so much from my conversations with people about poetry and paintings during that little tour; it inspired me to revise and expand those lectures the following summer.

And then I kept idly tinkering with things, daydreaming about adding new material, or maybe taking some things out, for too many years afterward. I wanted to say something more conceptually unified and ambitious than the original three talks (which felt sort of miscellaneous and all-over-the-place to me in retrospect). I tried to think about poetry as a technology of feeling, and about other historical traditions like Japanese haiku and the ghazal in Persian and South Asian poetry. Time passed. Trump happened. COVID happened.

Finally, I realized the three little original talks, in all their eccentricities and discontinuities, said more about poetry (and about me) than any sort of expansive statement about the art of poetry writ large. I e-mailed my incredibly thoughtful and supportive editors at Wave Books and said, “Why don’t we just publish the lectures as they were back in 2016?” Even though I finished them eight years ago, it took all that time to realize that they were done!

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I tried to let the paintings and poems show me what to think (and feel) about art. I didn’t want to bring my own ideas to the artworks; I wanted my thinking to emerge from close intensive contact with the surfaces of paintings and with the linguistic textures of poems. I didn’t know where I was going before I started looking and reading—and that was challenging and exciting, to discover that what I was really interested in was, say, the deep background of Bruegel’s painting Landscape With Fall of Icarus, or Emily Dickinson’s wild similes, or why nobody really looks at Achilles’ shield in the Iliad.

What most amazed me, in the end, was how generous people were in looking at those paintings and poems with me when I delivered those lectures. It felt like, yes, you can trust your own looking and feeling, and others will go with you—even if you find weird things, like a pyramid inside a poet’s head in a painting, people will try to see it too.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I mostly write in my office at school, because my wife writes at home, where we don’t have much room to spread out. I need to feel like I’m the only person around who’s making art—otherwise I start wondering what the other writer is up to, in a distracting sort of way. Fortunately, my colleagues down the hall at the university aren’t poets—they’re scholars, so I don’t feel like I’m just another worker-bee in some sort of literary hive-mind when I’m at school.

I used to try to write every morning at work, but that almost never happens lately—I’m too busy with administrative work and teaching and editorial correspondence. So now I mostly write when I’m on leave from teaching, or in the summers. But during those open times, I try to write every morning, for three or four hours at a stretch—sometimes even a little longer if I can.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading a lot of poetry submissions to the Paris Review, where I’m the poetry editor. We receive 1,500 submissions every season during our open reading periods in autumn, winter, fall, and spring—and of course many more poems come in from publishers and other ways throughout the year, so that leaves little time for reading novels or philosophy like I used to.

We also receive over 300 poetry manuscripts every year for the Phoenix Poets book series at the University of Chicago Press, which I coedit with Rosa Alcalá, Douglas Kearney, and Katie Peterson. I’m mostly just reading work by the poets of the future! It’s immensely rewarding, but I do miss having time to dive into something old, like The Faerie Queene, and really live inside it over an extended period of time.

But I do sneak in some reading here and there—though I rarely finish what I start. I read some parts of the Icelandic sagas this summer and loved them. I’m a sucker for anything with characters who have names like “Unn the Deep-Minded.”

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I’m a big fan of Eliot Weinberger’s writings—as a translator, as an essayist, and as someone whose life’s work feels to me like a wondrously unified yet multi-faceted epic poem in many ways. Whether it’s his translations of Jorge Luis Borges or Bei Dao, or his essays on bees or angels, everything connects to everything else in his writing in a manner that feels, to me, deeply poetic.

But Weinberger would probably wince to hear himself described this way—and that’s what I love most about his literary sensibility. There’s nothing grandiose to his style or his perspective on things—but the universe feels bigger, deeper, and older when you read his books.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

I’m surely my own greatest impediment as a writer. I can always find reasons not to write—whether it’s university committee work or e-mailing authors who’ve submitted their poetry to the Paris Review or to Phoenix Poets or answering author’s questionnaires about the biggest impediment to my writing life. I could blame academia or editorial work or Poets & Writers Magazine—but it’s really me!

Then again, I think all those other things really do enrich the writing I do when I find time for it. I have no complaints.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

I don’t have an agent, but the editor at Wave Books I worked with most closely in the endgame of putting together The Unsignificant was the amazing Heidi Broadhead. She’s an incredibly thoughtful reader who quietly yet very artfully makes it possible for you arrive at a new understanding about things on your own as a writer. Heidi never “told me” to do anything, but I remember that she floated the possibility of ultimately ordering the lectures in The Unsignificant in a different way than I’d first envisioned the sequence. Originally, I’d assumed that I should begin with the lecture that’s about wonder as the emotional condition for beginning a poem—but Heidi asked if I might like to end with that lecture instead, to end with the question of beginnings. And that was exactly the right way to go.

It's funny, as an editor myself when I work with writers, I’m usually more hands-on when it comes to line edits—I’m always thinking about how little micro-tweaks here and there can change the tone or the image-construction of this or that poem. But I’d like to be more like Heidi and see the larger structural possibilities for reshaping a book on the global level—to me, that’s an amazing thing to do for another writer.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Unsignificant, what would you say?

I’d say trust your audience even more than you trust yourself. That will let you discover things you couldn’t discover on your own. You can explore what you’re unsure about, and if you acknowledge your own uncertainty, others will help you understand what you’re trying to find. Maybe the lecture format lends itself to this sort of collaborative inquiry more naturally than a traditional book of essays. In the end I’ve never really liked the word lecture for this kind of work—it feels too authoritative. “Talk” feels more like a conversation, in the spirit of this exchange, to me.

Now that they’re published in book form, the lectures have moved into a different relationship to their audience. They aren’t oral performances anymore—they’re the record of those performances. Publication introduces a new dimension to the lectures as an experience. Now you can push pause, rewind, or skip ahead in the talks by flipping through the book’s pages or rereading this or that passage. You lose the intimacy of live performance, but you gain the luxury of dwelling on the text and images at your own pace.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of The Unsignificant?

Paintings were at the heart of this work. Bruegel, Picasso, Chardin—I’m almost embarrassed to say, canonical paintings that you find in art history books or courses really shaped my thinking about the poems in these talks. That’s probably because I’m not a specialist in art history—I just like to look at paintings in an amateurish kind of way, like most other people visiting a museum. Maybe those paintings simply offered me a way of thinking about the art of looking—at paintings, but also at inkblots in a Rorschach test, or Galileo’s drawings of the moon, or oneself in the grips of a great poem.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

This isn’t writing advice, but it’s great advice for writers and for pretty much anyone in all sorts of situations. I once heard someone talking about an art studio course where the instructor was circling the room, looking at students’ work while they were making their sculptures. The instructor stood behind one student who was struggling with a project, maybe overthinking it and trying all sorts of different things that just weren’t working—and becoming hopelessly tangled and frustrated in the process. The teacher whispered into the student’s ear, “Let it be latent.”

I have no idea if that helped the student or if it just worsened their perplexity, but it’s helped me again and again as a writer. Whenever I start to feel like I’m forcing things, I try to remember to “let it be latent”—to trust that what you’re trying to bring out might already be there, perceptible to others, informing what you’re trying to do from within. Maybe it’s just me, but it always helps.