This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Steve Wasserman, whose book Tell Me Something, Tell Me Anything, Even If It’s a Lie: A Memoir in Essays, is out today from Heyday Books. The memoir takes readers on a journey through Wasserman’s career in books, featuring personal reflections on Susan Sontag, Huey Newton, Barbara Streisand, W. G. Sebald, and Christopher Hitchens. These essays include the story of a bookstore owner who wouldn’t let Wasserman buy the books he wanted, eulogies of close friends, and Wasserman’s assessment of the fast-changing world of publishing. Viet Thanh Nguyen calls Wasserman a “troublemaker of the good kind since his youth,” who “continues to inspire with his vigorous dedication to the life of the mind, exhibited with clarity and grace in this book.” Joyce Carol Oates calls the book “intensely personal, engaging, and illuminating,” and Hilton Als says, “to not follow [Wasserman’s] quicksilver intelligence and bountiful heart in these wonderful pages would be criminal.” Steve Wasserman, who was raised in Berkeley, is Heyday’s publisher; formerly he was editor-at-large for Yale University Press, editorial director of Times Books/Random House, and publisher of Hill and Wang and the Noonday Press at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. A founder of the Los Angeles Institute for the Humanities at the University of Southern California, Wasserman was a principal architect of the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books during the nine years he served as editor of the Los Angeles Times Book Review, from 1996 to 2005.

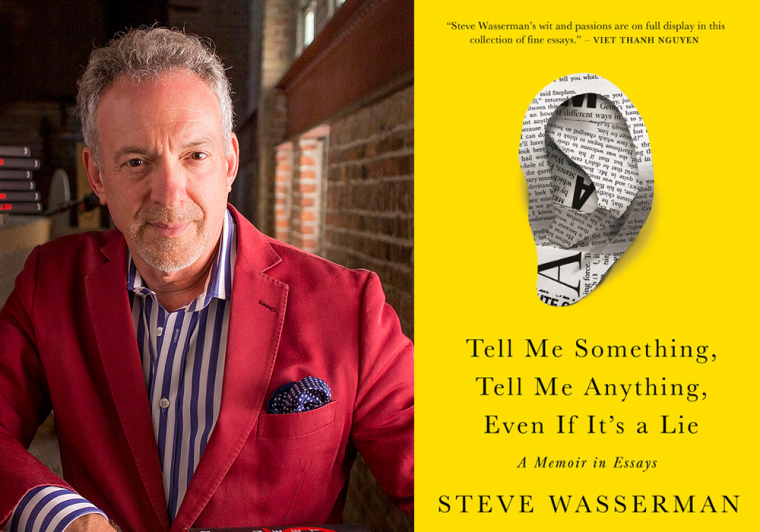

Steve Wasserman, author of Tell Me Something, Tell Me Anything, Even If It’s a Lie: A Memoir in Essays. (Credit: Dennis Anderson)

1. How long did it take you to write Tell Me Something, Tell Me Anything, Even If It’s a Lie: A Memoir in Essays?

My book comprises thirty essays written and, for the most part, previously published over the past nearly fifty years in a wide variety of diverse publications, ranging from the New Republic and the Nation, the American Conservative and the Progressive, the Village Voice and the Los Angeles Times, the Threepenny Review to the Times Literary Supplement. Choosing which of them survived the occasion for which they were first written was the main challenge. To my surprise and delight, they added up to a book of some 100,000 words, united by a number of elective affinities, ranging over politics, literature, and the tumults of a world in upheaval. Taken together, they offered up a story of the awakening and evolution of my own sensibility as I fell through time and circumstance.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Arranging the essays in an order that ensured that the sum of the parts was greater than any individual piece. And to revise, as seemed appropriate, to invite the reader to accompany me on my own, often exhilarating, journey through the world of books, ideas, and activism. More: To make sure that the reader awakens to the delights and seductions of an insatiable, driven capacity for curiosity about our often broken world and the embarrassment of riches that it provides if only we can pay attention.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

As little as possible, but when I begin dreaming in sentences, then I know it’s time to buckle down and lash myself to the laptop and begin typing. Soon one sentence prompts another and I’m off to the races. Procrastination is my enemy; my conceit is that it is also my ally, especially when I regard it as synonymous with thinking. Carving out the solitude necessary for thought is a prerequisite for writing. Late-night quiet is helpful. Also a good cup of coffee...or two or three.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m a promiscuous reader and am in the middle of a quartet of books: What Nails It (Yale University Press, 2024) by the indispensable and gifted Greil Marcus; Creation Lake (Scribner, 2024) by the wondrous wordsmith Rachel Kushner; The Lions’ Den: Zionism and the Left from Hannah Arendt to Noam Chomsky (Yale University Press, 2019) by the brilliant and courageous Susie Linfield; and Zhou Enlai: A Life (Harvard University Press, 2024) by the remarkable historian Chen Jian.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

The late Czech master storyteller Bohumil Hrabal, especially his novella, Too Loud a Solitude, a tale about the indestructibility of books and knowledge. Written in the form of a first-person monologue (or, perhaps, a confession), here in its entirety and beautifully translated by the late Michael Henry Heim is the glorious first paragraph:

“For thirty-five years now I’ve been in wastepaper and books, smearing myself with letters until I’ve come to look like my encyclopedias—and a good three tons of them I’ve compacted over the years. I am a jug filled with water both magic and plain; I have only to lean over and a stream of beautiful thoughts flows out of me. My education has been so unwitting I can’t quite tell which of my thoughts come from me and which from my books, but that’s how I’ve stayed attuned to myself and the world around me for the past thirty-five years. Because when I read, I don’t really read; I pop a beautiful sentence into my mouth and suck it like a fruit drop, or I sip it like a liqueur until the thought dissolves in me like alcohol, infusing brain and heart and coursing on through the veins to the root of each blood vessel. In an average month I compact two tons of books, but to muster the strength for my godly labors I’ve drunk so much beer over the past thirty-five years that it could fill an Olympic pool, an entire fish hatchery. Such wisdom as I have has come to me unwittingly, and I look on my brain as a mass of hydraulically compacted thoughts, a bale of ideas, and my head as a smooth, shiny Aladdin’s lamp. How much more beautiful it must have been in the days when the only place a thought could make its mark was the human brain and anybody wanting to squelch ideas had to compact human heads, but even that wouldn’t have helped, because real thoughts come from outside and travel with us like the noodle soup we take to work; in other words, inquisitors burn books in vain. If a book has anything to say, it burns with a quiet laugh, because any book worth its salt points up and out of itself. I’ve just bought one of those minuscule adder-subtractor-square-rooters, a tiny little contraption no bigger than a wallet, and after screwing up my courage I pried open the back with a screwdriver, and was I shocked and tickled to find nothing but an even tinier contraption—smaller than a postage stamp and thinner than ten pages of a book—that and air, air charged with mathematical variations. When my eye lands on a real book and looks past the printed word, what it sees is disembodied thoughts flying through air, gliding on air, living off air, returning to air, because in the end everything is air, just as the host is and is not the blood of Christ.”

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Conquering a lifelong case of imposter syndrome.

7. What is one thing your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

No one is getting any younger. Buckle down and get it done.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Tell Me Something, Tell Me Anything, Even If It’s a Lie, what would you say?

Not to unduly question the arrogance that is the birthright of youth and to understand that the hubris I harbored was merely a necessary and not at all discreditable prerequisite to realizing ambition.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Tell Me Something, Tell Me Anything, Even If It’s a Lie?

I seem to be someone determined to work almost every station in the publishing kitchen. The short answer is life itself. I hold with Henry James: “Live all you can; it’s a mistake not to.”

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Never let the pursuit of perfection be the enemy of the good.