This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Subhaga Crystal Bacon, whose new poetry collection, Transitory, is out today from BOA Editions. In this searching consideration of gender that bridges the personal and political, lyric and docupoetics, Bacon elegizes forty-six trans and gender-nonconforming people who were murdered in the United States and Puerto Rico in 2020. The elegies—whose titles contain the name, age, and death date of each life—memorialize those lost and bear witness to the mounting toll of violence against people whose gender falls outside the normative binary. Bacon, who uses she/they pronouns, explores their own coming of age in the years after the 1969 Stonewall Uprising opened the door to greater openness for queer people and increased activism demanding social inclusion and equal rights. Without drawing an equivalence between the lyric “I” and the lives mourned in Transitory, Bacon nonetheless explores parallels, including experiences of discrimination and violence the speaker encounters at work as a teacher and on other fronts. Aware of the problematics in Transitory’s monumental project, Bacon incorporates metacommentary and reflection about “the need to name this, the brutality of tallying the dead,” as she puts it in “Why I’m Writing About the Murders of Trans & Gender Nonconforming People in the Year of COVID.” Diane Seuss praises Transitory, particularly its use of poetic form: “The forms provide elegance. Dignity. The details, affinity.... I could feel each loss with profundity.” Subhaga Crystal Bacon is the author of Blue Hunger (Methow Press, 2020) and Elegy With a Glass of Whiskey (BOA Editions, 2004). They live on the eastern slopes of the North Cascade mountains in Twisp, Washington.

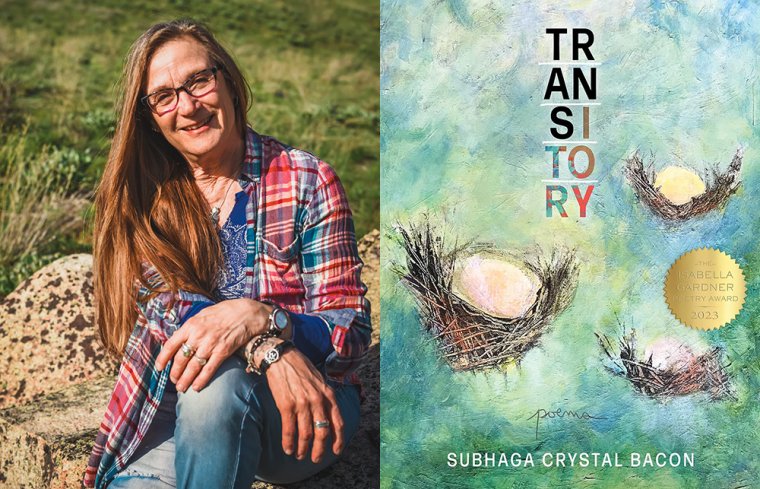

Subhaga Crystal Bacon, author of Transitory. (Credit: AKR Photography)

1. How long did it take you to write Transitory?

I wrote the first poem in early July 2020 during a workshop about writing poems of protest in form. That first poem was an acrostic for the word justice, repeated twice to accommodate the twenty-one transgender people murdered since the start of the year. I knew once I’d finished that catalog that I’d have to write a poem for each of those who were murdered that year. I finished the bulk of the manuscript in December then began fleshing it out with some personal poems to provide context as to why I had written the collection.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Tracking the reports of these murders was extremely painful. I checked the Human Rights Campaign website a couple times a week. Some weeks there’d be nothing and in others a record would appear of a death that had happened earlier in the year. Or the death of a teenager, like Brayla Stone, who was only seventeen. Then I’d spend days reading everything I could find online, taking notes and thinking about the poem’s form, living with grief and loss. There were some very low days for me, when I’d be holed up in my study working and emerge at the end of the day really weighed down by what preciousness had been stolen from families and friends.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’ve tended to alternate between my study and our kitchen table. My partner is a painter and spends most of her day in her studio, so it’s really best for me to work in my own studio space. I recently did some rearranging of books and sort of “fluffed up” the space so it’s more inviting again. It’s a nice room, and it’s good to be able to close the door and carry on if my partner comes in to eat during the day, keeping our shared space communal rather than expecting her to tiptoe around if I’m at my computer.

I retired from college teaching last June, and I love having the freedom to write every day if I want, apart from the month of April, when in the last couple of years I’ve written a poem a day. I work in an intuitive way. I have a very interior life and am frequently investigating myself, my thoughts and feelings, my memories and impressions, so I’m grateful to have the freedom to follow those impulses and see where they lead. We live on beautiful, spacious, open land, on about thirty acres in north central Washington that bump up against undeveloped land. We take turns walking our labradoodle, Lola, out there, and I often write on my phone during our walks. If I’m not writing, I’m revising or submitting new work. So I’m writing in some way most days.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m just back from the Lit Youngstown Fall Literary Festival in Ohio, where I was on a panel with Jennifer Martelli, Jessica Cuello, and Stacy Gnall on poetry of witness. I was lucky enough to snag a copy of Jessica’s first book, Pricking. It’s an enthralling collection about medieval French history and the persecution of Cathars [a sect of Christianity], Jeanne d’Arc, and “witches,” so it feels timely and deeply connected to anti-trans violence and state-sponsored persecution. She’s one of my favorite poets.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

The book mostly organized itself as I arranged the poems chronologically in order of the deaths. The more challenging work was integrating the poems about my own queer journey and experiences with homophobia and threats of violence, my history as a queer person who’s been blessed to live to elderhood. I have a wonderful group of writing friends from my MFA cohort at Warren Wilson College, and they helped me to place those poems. The book starts with a long poem I wrote in August 2020, when there were no deaths reported. It’s a poem that situates me as the “watcher” and gives some context for what that was like. I scattered the personal poems every so many pages to provide a kind of relief from the otherwise unrelenting horror of the murders.

6. How did you arrive at the title Transitory for this collection?

The word transitory came to me early on to resonate with transness and with all the things trans can mean as a prefix. Life is transitory— but more so for trans people, particularly people of color, for whom the life expectancy is thirty-five years. The original title was Transitory: A Catalog of Gleaned Sketches of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming People Murdered in 2020. It’s unwieldy but I wanted something that would point to how little information there is about these lost lives. In the end my writing group suggested just Transitory, to let it be more evocative and less literal. They were right of course. And what Sandy Knight did with that word on the cover, conjuring both the words trans and story, is brilliant!

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Transitory?

You know, I recently read an interview with the poet Joshua Jennifer Espinoza in the anthology Subject to Change: Trans Poetry & Conversation, in which she says, “Investigating your own gender—whether you are cis or trans or anything else—allows you to experience the world in a new way, allows you to be more sensitive to the oppression faced by those whose gender is not legible within this system.” As a queer-identified person of a certain age, I came late to investigating gender identity. It was surprising to me how little I both understood and was comfortable with my own gender. Once people started talking about this more and identifying themselves and their pronouns, I went through a shift from queer and cis, to queer and nonbinary, to queer and “anything else,” something that feels quietly trans-masculine. The final poem in the collection started out titled “Cis/Sister” but is now titled “This/Sister.” I finally have the language and freedom to know myself in this way, as my true nature. It’s a deeply personal knowing that shows itself only shyly. I wish I’d remembered to edit my bio in the book to reflect my pronouns correctly as she/they.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Transitory, what would you say?

It’s okay for you to reveal more of yourself in your poetry! There’s a poem in the collection titled “I Have Room for You in Me: A Litany,” and it’s addressed as much to myself as to others.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

My true work is spiritual awakening into my true and total nature. The tradition in which I teach and practice, Trillium Awakening, is a tantric path, which means that we accept everything as it is. It’s not a transcendent path of up and out but an embodied path that accommodates and welcomes the down. Writing this book took me into the down in a big way, living briefly the lives and dying the deaths of those I elegized. Without my spiritual capacity I don’t know if I’d have had the stamina to do it, to keep tracking the deaths and bringing them into the light—to the limited extent I was able to.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

My early teacher, Larry Levis, told me that I scared myself and backed off of going where the poem wanted to go. He was right! I recently read a piece in Poetry by Kiki Petrosino that was good advice on this count, to enter “the field of language dressed as a pilgrim, not a tractor...to witness, to encounter, to love those poems onto the page. Love; this is the work.”