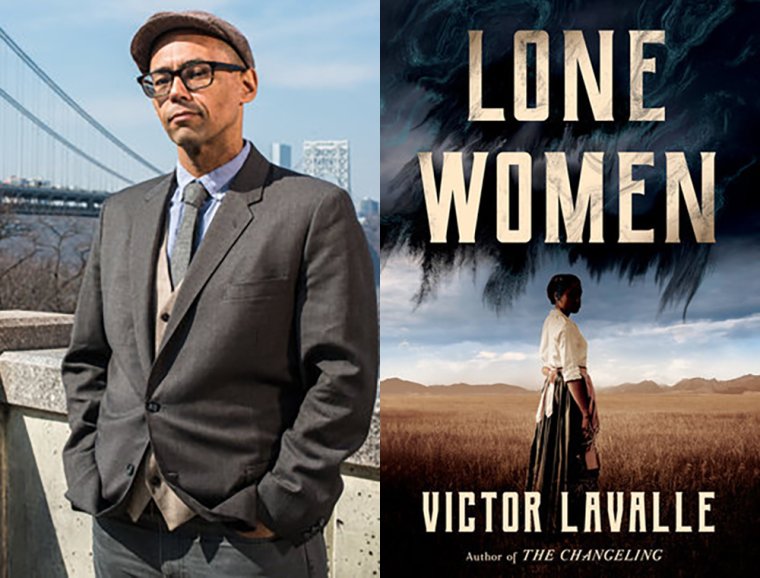

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Victor LaValle, whose new novel, Lone Women, is out today from One World. In this gothic western, a woman named Adelaide Henry tries her luck as a Montana homesteader fifteen years after the turn of the twentieth century, accepting free land from the U.S. government as part of its westward expansion efforts. For Adelaide, Montana represents the chance for a fresh start after tragedy in California, where her parents died under horrific circumstances. But as a Black woman in a largely white community, she feels isolated and vulnerable. Struggling mightily to protect herself and keep her family secrets at bay, Adelaide carries with her a locked steamer trunk, inside of which a powerful curse threatens her every move. “A counter to the typical homesteading narrative, this moody and masterful western fires on all cylinders,” writes Publishers Weekly. “Readers are sure to be impressed.” Victor LaValle is the author of five novels, including The Changeling (Spiegel & Grau, 2017), a short story collection, and two novellas. The recipient of numerous honors, including the American Book Award and Shirley Jackson Award, he teaches at Columbia University.

Victor LaValle, author of Lone Women. (Credit: Teddy Wolff)

1. How long did it take you to write Lone Women?

Lone Women began as a long story for an anthology called Long Hidden: Speculative Fiction from the Margins of History, which was published in 2014. I wrote the story, thought I was done, but couldn’t stop thinking about the women in the tale. After letting it rest while I wrote another novel called The Changeling, I got back to Lone Women around 2018 and finished in 2022. So it either took me four years or nine, depending on how you count.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Two choices: Writing a convincing cast of women, or writing a convincing portrayal of Montana. I’m a guy from Queens who usually writes about men from New York City. I had to not only transform into different people and places, but to also find myself within both of those.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

After the pandemic, we moved into a house in the Bronx. Big change from the two-bedroom apartment where we were living with our two kids. Three bedrooms, what a difference! And enough space that I’ve got an office of my own now. I work there four or five days a week. I write for two hours each day, no more than that. The quality of my writing, and thinking, drops off a cliff if I work for any longer.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Mott Street by Ava Chin. Chin traces the history of her family, going back decades, from coast to coast. It’s a personal history and offers insight about American history through the lens of her family.

Our eleven-year-old is also ready to try Stephen King, so I’ve bought us two copies of his first collection, Night Shift. We’ll read the stories together.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Stephen King feels pretty formative, as are Shirley Jackson and Clive Barker. I love Graham Greene’s novels, his “entertainments” even more than his supposedly serious ones. Ishmael Reed is foundational for his grasp of politics and history blended into narratives that become weirder and wilder in service of some very serious ideas.

6. What trait do you most value in your editor or agent?

I have the incredible good fortune of working with the same agent for my whole career so far—Gloria Loomis, twenty-five years and counting—and the same editor for all but two of my books: Chris Jackson, for twenty years or so. What this means is that they’ve seen me grow, shrink, stagnate, and change. But no matter how long it’s been, and no matter what place I’m in, I’ve always believed they wanted to help me write the best version of my book that I can. They might disagree with certain plans I have, or ways I’ve tried to execute those plans, but they never try to make me a different writer than I am. That’s as close to unconditional love as I can imagine in a professional relationship like ours. I am endlessly grateful for it.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Lone Women?

The existence of “lone women” as a part of the homesteading experience in Montana was my first and biggest surprise. It’s what spawned this entire novel. I just hadn’t learned there were women who went out to the territories truly alone and settled in. The idea went against so much of the bias I had based on popular entertainment and my idea of the West. In a way, this whole novel was an attempt to dispel those biases.

8. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

Standing in the campus bookstore at the University of Montana and finding a book, Montana Women Homesteaders: A Field of One’s Own by Sarah Carter. I plucked it off the bookshelf because of the subject matter, and the Virginia Woolf allusion. What good luck for me that this was the book that pulled me in.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I did lots of research. Maybe the most fun part of that was reading the archives of the Bear Paw Mountaineer, the local paper for the county where my novel is set. It was published on a weekly basis, and I spent months reading (or at least scanning) every issue that ran from 1911 to 1916. There was no better way to get a feel for the life of the town than this. I loved it, even though it could get tedious as hell at times.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

Once, while I was a student in an MFA program, one of the other students turned in a piece with a handful of literary references woven into the text, the kind of things we really should’ve known as graduate students. More than half of us didn’t know the references, and our professor (who I won’t name) yelled at us for five minutes straight about our lack of deep reading. How can you be writers who don’t read? he demanded. Even in the moment I knew he was right. So that’s the best writing advice I ever received. If you’re going to be a writer, you better damn well be a reader.