Among the many new books published each season is a shelf full of notable anthologies, each one showcasing the work of writers united by genre, form, or theme. The Anthologist highlights a few recently released or forthcoming collections, including This Is the Honey: An Anthology of Contemporary Black Poets (Little, Brown, February 2024).

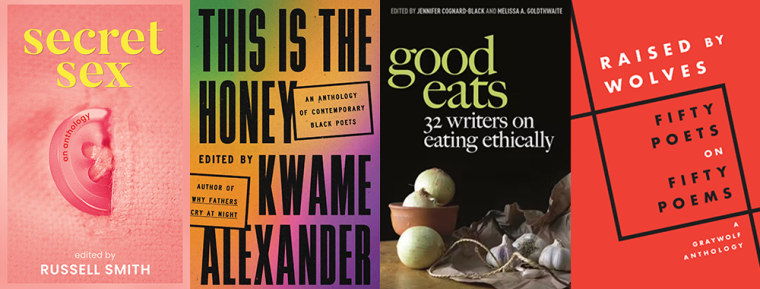

It is a truth universally acknowledged that sex is among the most difficult subjects to write about. U.S. authors can blame Puritan prudishness baked into the national DNA, and Canadian writers are apparently equally uptight. So says Russell Smith, editor of Secret Sex (Dundern Press, January 2024), which gathers erotic fiction by two dozen Canadian authors ranging in age from their twenties to their seventies, including francesca ekwuyasi, Pasha Malla, Heather O’Neill, and Zoe Whittall. But good luck trying to figure out who wrote what: While contributors’ names are listed at the front of the anthology, the stories in Secret Sex do not have bylines. This is not an editorial oversight but part of the volume’s design. Smith wondered: What would happen if he “gave a selection of literary writers the opportunity to write sex scenes, or reflections on sex, and share them, without any fear of identification? Would they write more explicitly, more openly.... The answer is a dramatic yes,” he writes in his introduction to the collection. In language ranging from lyrical to droll, these stories consider pornography, sexting, the varieties of coitus—and, yes, even romance. By turns graphic, tender, melancholy, and comical, Secret Sex offers a nuanced exploration of sexuality and the many complications, surprises, sorrows, and joys it can bring to human life.

In his introduction to This Is the Honey: An Anthology of Contemporary Black Poets (Little, Brown, February 2024), editor Kwame Alexander describes the collection as holding space for the “in between” Langston Hughes evokes in his poem “Advice”: “Folks, I’m telling you, / birthing is hard / and dying is mean / so get yourself / a little loving / in between.” As Alexander envisioned this anthology, he interpreted the phrase “in between” to mean “a gathering space for Black poets to honor and celebrate. To be romantic and provocative. To be unburdened and bodacious.” These descriptors aptly capture this generous compendium of verse by more than one hundred living Black bards considering subjects including the meaning of home, romantic love, child rearing, grief, and politics. In “Dear Barbershop,” Chris Slaughter traces his lineage to the titular salon: “I come from you: every argument, debate and dare— / every hand-me-down bet that taught me to run,” he writes. Morgan Parker’s “Beyoncé on the Line for Gaga” lionizes the Black pop star and offers a critique of the white one, while subtly opening space for solidarity between the two: “Give me your hand / and I will let you back this up,” she writes in Beyoncé’s voice. Chris Abani, Derrick L. Austin, Terrance Hayes, Rickey Laurentiis, Roger Reeves, Clint Smith, Tracy K. Smith, Natasha Trethewey, Marcus Wicker, and many others offer odes, elegies, prose poems, and lyrics “full of hope and humor and humanity of a proud people who hold the promise of tomorrow in their hearts,” as Alexander puts it.

The term food writing often conjures visions of restaurant reviews, recipe blogs, or reportorial accounts of culinary trends. But Good Eats: 32 Writers on Eating Ethically (NYU Press, January 2024) showcases the literary side of the genre with personal essays exploring edible nourishment and its relationship to place, identity, history, and social systems. Edited by writers and academics Jennifer Cognard-Black and Melissa A. Goldthwaite, Good Eats considers deep questions about our connection and access to food, the stories we tell about it, and their effects on our bodies, communities, and planet. Some entries speak directly to the philosophical dimensions of the title. Lynn Z. Bloom’s “Do I Have to Give Up Chocolate? An Ethical Dilemma,” for example, unpacks the internal conflict “a woke consumer” experiences as she confronts her hankering for cacao: “Every aspect of the production process represents exploitative working conditions, all reprehensible and unethical,” she writes. Other essays offer looser approaches to ethical eating, such as Will Becker’s “Men & Meat,” which investigates the connections among animal-flesh-as-food, masculinity, and sexuality. In “My Body, Our Body, Her Body,” Cognard-Black reflects on the disordered eating habits she developed in childhood and how to communicate with her daughter about food and body image. Ross Gay, Nikky Finney, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, and others contribute selections in “language that engages the body’s senses alongside the mind and spirit,” as the editors put it in their introduction.

Graywolf Press, one of the nation’s most influential independent publishers, celebrates its fiftieth anniversary this year. Since 1974, the press has published more than four hundred poetry collections. While it is also a home for fiction and creative nonfiction, “poetry that span[s] a range of styles and visions remains at the heart of Graywolf’s mission,” Carmen Giménez, the press’s publisher and executive director, says in her introduction to Raised by Wolves: Fifty Poets on Fifty Poems (Graywolf Press, January 2024). The anthology gathers verse and criticism by Graywolf authors invited to “select and write about poems they love by other Graywolf poets,” celebrating “connections and lineages” across the decades, writes Giménez. The anthology opens with Kaveh Akbar’s “The Miracle” and Leah Naomi Green’s exploration of the way the poem “holds a holy space empty by surrounding it with words, then striking those words to reverberate, like a bell.” Other inspired pairings include Claire Schwartz’s consideration of Elizabeth Alexander’s “Stray,” Saskia Hamilton’s meditation on Catherine Barnett’s “Accursed Questions, iv,” and Danez Smith’s contemplation of Donika Kelly’s “The moon rose over the bay. I had a lot of feelings.” The last line of verse in the collection—from Monica Youn’s “Hangman’s Tree”—could double as a tagline for this anthology or for Graywolf itself: “It will keep you alive.”