Something extraordinary has happened to Philip Roth over the past ten years or so. Gradually, though irrefutably (and without any assistance whatsoever from Oprah Winfrey), he has become our Great American Novelist. Although Roth began racking up his prodigious collection of literary honors and awards early on, including the National Book Award for his very first collection of fiction, Goodbye, Columbus (Houghton Mifflin, 1959), one could argue that the 1993 publication of Operation Shylock: A Confession (Simon & Schuster), which won the PEN/Faulkner Award, marks the true beginning of Roth’s furious run to muscle out any literary competitors for the aforementioned title. In the thirteen years since Operation Shylock appeared, Roth has won (among other awards) a National Book Award for Sabbath’s Theater (Houghton Mifflin, 1995), a Pulitzer Prize for American Pastoral (Houghton Mifflin, 1997), a PEN/Faulkner Award for The Human Stain (Houghton Mifflin, 2000), and the PEN/Nabokov Award in 2006 to honor a body of work “of enduring originality and consummate craftsmanship.” What’s more, in 2005 Roth became only the third living American writer to have his work published in the prestigious Library of America series. The first two of eight volumes have been published; the last is scheduled to appear in 2013.

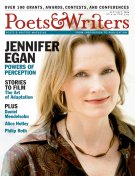

Philip Roth in March 1985 and (right) in March 2006. (Credit: Nancy Crampton)

The outcome of a New York Times Book Review survey, featured in the May 21, 2006, issue, perhaps most arrestingly affirms Roth’s titan status. The editors asked several hundred eminent writers, critics, and editors to name “the single best work of American fiction published in the last twenty-five years.” While Toni Morrison’s Beloved (Knopf, 1987) received the most votes, six Roth titles—six!—were among the twenty-one runners-up that garnered multiple votes.

Mainstream readers have responded in kind to the critical reception of Roth’s more recent work. His last big novel, The Plot Against America (Houghton Mifflin), has sold in excess of four hundred thousand copies since its release in 2004, while his most recent effort, Everyman (Houghton Mifflin, 2006), appeared for several weeks on the New York Times best-seller list. Suddenly, one hears allusions to Roth or his books in the unlikeliest of contexts. The coup de grâce for me was hearing Cornel West casually invoke Roth’s Everyman, apropos of pretty much nothing, during the season finale of the HBO show Real Time With Bill Maher. The allusion seemed all but lost upon West’s copanelists, and upon Maher himself. But still.

Famously reclusive (never quite a J. D. Salinger or Thomas Pynchon, but lean-ing in that direction), Roth has gradually warmed to his role as America’s preeminent novelist. In fact, by writerly standards, he has been downright gregarious of late. Notably, he visited with David Remnick, the editor of the New Yorker, for several interviews, which culminated in a substantial profile of the author in the May 8, 2000, issue of the magazine, coinciding with the publication of The Human Stain. More recently, he has been a featured guest on both NPR’s Fresh Air and PBS’s Newshour. Upon the publication of The Plot Against America, he even sat for an interview in his Connecticut home with Katie Couric of the Today show. The results of the recent New York Times Book Review survey will only generate more interest in Roth—more interviews, more casual invocations of the master’s name from every quarter.

While a part of me celebrates these heady developments, I can’t deny the possessive, proprietary feelings that curiously obtain with equal force. Like several of my young(ish) Jewish American peer writers and critics, I cut my teeth as a reader of serious books in the 1980s, and immediately came under Roth’s thrall. Indeed, one cannot overstate Roth’s impact on my generation of aspiring Jewish American writers. Although it might be difficult to fathom from our current vantage, these were generally bear-market years for Roth—post-Portnoy, pre-Zuckerman-as-elder-statesman. Roth’s fiction during this middle period tended to be either ignored or willfully misread as the thinly veiled autobiographical work of a misogynist or navel-gazer—which goes some way toward explaining his retreat to the verdant woods of Connecticut in the late 1970s. And so part of me now wishes to declare, “Hey, Cornel! Hey, Katie and all you other Johnny-come-latelies! Buzz off and find your own literary hero!”

But, beyond this visceral recoil, what worries me is the narrow, nearly patrician image of Roth that now threatens to gain firm purchase on the collective consciousness. For, if Roth’s increasingly familiar visage fairly evokes a crumpled Robert Frost, the celebrated prose of late also hews to a quieter, even more elegiac, tone. “It’s not that the books necessarily have any less vivacity, any less imaginative brilliance,” Daniel Mendelsohn recently observed in the New York Review of Books. “It’s merely that they seem, suddenly, to be written by some-one who’s closer to the periphery than to the center of things, who’s looking back in resignation, or anger, or both.” Given this context, it seems ever more important to read across the trajectory of Roth’s long career. For, to explore Roth’s evolving oeuvre is to encounter, above all, a dynamic and uncompromising craftsman who ought still to inspire emergent writers.

![]()

One must begin with those sentences, with that full-throated brio. The old adage “Jews are just like everyone else, only more so” was fully realized in the breathless, oft-italicized, and exclamatory prose of Portnoy’s Complaint (Random House, 1969). One could turn to almost any page, but, consider, for example, Portnoy’s fevered reflections upon his mother’s brand of discipline:

There is a year or so in my life when not a month goes by that I don’t do something so inexcusable that I am told to pack a bag and leave. But what could it possibly be?… My homework is completed weeks in advance of the assignment—let’s face it, Ma, I am the smartest and neatest little boy in the history of my school! Teachers (as you know, as they have told you) go home happy to their husbands because of me. So what is it I have done? Will some-one with the answer to that question please stand up! I am so awful she will not have me in her house a minute longer. When I once called my sister a cocky-doody, my mouth was immediately washed with a cake of brown laundry soap; this I understand. But banishment? What can I possibly have done!

These pitch-perfect cadences seemed effortlessly to capture the temperament of our postwar Jewish-American families. We didn’t know we could write like that! We had obediently read Henry James, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and Edith Wharton during high school and those early collegiate years. James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, and William Faulkner offered something else entirely, but these were not syntactical or linguistic models that could be of any use to our sensibilities. True, Saul Bellow had earlier broken loose from the shackles of blue-blooded American prose with The Adventures of Augie March (Viking, 1953), introducing his own crackling version of the American sentence to the literary scene. Roth has acknowledged his debt to Bellow’s novel, most pointedly, in his essay “Rereading Saul Bellow,” published in the October 9, 2000, issue of the New Yorker. Yet, for a writer of my generation, there was always something otherworldly about Bellow’s vernacular, those syntactical inflections of Yiddish. “I am an American, Chicago born—Chicago, that somber city—and go at things as I have taught myself, free-style, and will make the record in my own way: first to knock, first admitted; sometimes an innocent knock, sometimes a not so innocent.” We could admire the audacity of such sentences, but we could never write such sentences, any more than Roth—who is Bellow’s junior by a crucial eighteen years—could emulate Bellow’s style. Roth’s voice, by contrast, invoked the cacophonous music that resounded in our own childhood kitchens and family rooms.

Roth didn’t achieve this particular voice until his third novel. The prose of Goodbye, Columbus, Letting Go (Random House, 1962), and When She Was Good (Random House, 1967) smacks of Jamesian polish and restraint. The latter two books, at least, have been summarily dismissed as failures. In a 1994 essay, “How to Read Philip Roth,” Hillel Halkin spared nary a full sentence to dismiss these efforts as “ploddingly social-realistic stories set in the Midwest.” But there’s a lesson here to extract. More and more, it seems, the culture treats the endeavor of writing as a zero-sum game, exemplified by any number of factors: the ever-shrinking list of authors who demand an audience, the increasing thumbs-up or thumbs-down spirit of most book reviews, and even the recent (and, let’s face it, somewhat ridiculous) New York Times Book Review survey to identify the best work of American fiction of the last twenty-five years. Within this zeitgeist, we have little patience for a writer’s so-called minor works.

Yet, it seems important to recognize that the Roth who crafted the firecracker prose of Portnoy’s Complaint is the same author who crafted the contrastive prose (elegant at its finest) of his first three works, and that he could not have written the tempestuous music of Portnoy’s Complaint and the early Zuckerman novels—The Ghost Writer (1979) and Zuckerman Unbound (1981), both published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux—had he not first mastered other keys and pitches. Even the voices of Portnoy and the young Zuckerman were, like all voices, tied to a particular place and time, and were destined to be supplanted by other voices—specifically, by the more learned, contemplative, and brooding voice of an older Zuckerman, who, in American Pastoral, would fix a Whitmanesque eye upon the errant peregrinations of a fallen childhood hero from Newark, the Swede:

Well, he couldn’t commute from Down South but he could skip Maplewood and South Orange, leapfrog the South Mountain Reservation, and just keep going, get as far out west in New Jersey as he could while still being able to make it every day to Central Avenue in an hour. Why not? A hundred acres of America. Land first cleared not for agriculture but to furnish timber for those old iron forges that consumed a thousand acres of timber a year.... A barn, a millpond, a millstream, the foundation remains of a gristmill that had supplied grain for Washington’s troops.

Admittedly, not all longtime Roth admirers welcomed this new voice. Some lament this recent tonal shift, preferring their Roth red of tooth and claw. Fair enough. But to my mind the various permutations of the Rothian sentence might convey to working writers that we ought not grope for our one true voice so much as we should pay attention to the mani-fold voices that resound across the land-scape. One could argue that the inability or unwillingness to evolve in such a fash-ion has led more than a few of our strongest writers to silence or (à la Hemingway) unintentional self-parody.

Writers don’t set out to be one-book authors any more than presidents of the United States set out to be one-term incumbents. The elasticity and omnivorousness of Roth’s aesthetic sensibilities account, at least in part, for his longevity. His principal subject over the years has always been the multiform possibilities of being a Jew in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries (though Roth has always eschewed the label “Jewish American writer”). Driving him, apparently, is Roth’s nagging sense of his failure to successfully imagine these possibilities, combined with his fierce artistic determination to realize ever truer evocations of Jewish lives and counterlives. As Roth’s writer-protagonist Nathan Zuckerman reflects in American Pastoral,

And yet what are we to do about this ter-ribly significant business of other people, which gets bled of the significance we think it has and takes on instead a significance that is ludicrous, so ill-equipped are we all to envision one another’s interior workings and invisible aims?... The fact remains that getting people right is not what living is all about anyway. It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again. That’s how we know we’re alive: we’re wrong. Maybe the best thing would be to forget being right or wrong about people and just go along for the ride. But if you can do that—well, lucky you.

Indeed, Roth has tested the aesthetic boundaries of the novel throughout his long career, so that he might get right his panoply of major and supporting characters, so that he might imagine and evoke the divergent and polemical possibilities of being Jewish with greater, and then still greater, heft and resonance. Such is the overarching, cumulative feel of things as one reads one’s way through Roth’s canon.

![]()

Roth’s recent novel, The Plot Against America, in which he imagines Charles Lindbergh’s successful run for the U.S. presidency and the ensuing havoc wrought upon the nation’s Jews, was not the author’s initial foray into the fantastic. He seemed to know early on that to be a thoughtful Jewish writer in the twentieth century was to pose a series of “What if” questions. What if Kafka survived tuberculosis, and then the Nazi death camps? Might he have become a lowly Hebrew schoolteacher in Newark (in the short story “‘I Always Wanted You to Admire My Fasting’: or, Looking at Kafka,” of 1973)? What if Anne Frank survived typhus in Bergen-Belsen? Might she have immigrated to the United States and hidden her identity to preserve the legacy wrought by her published diary (The Ghost Writer)? What if a Czech Jewish writer modeled roughly upon the Polish Jewish writer Bruno Shulz managed to complete his masterpiece before the Gestapo murdered him (Zuckerman Bound; Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1985)? Kafka and Frank and Shulz were mythic Jewish lives that loomed large, and that continue to loom large, in the Jewish psyche. No other writer, however, dared imagine fictional counterlives for these hallowed members of the tribe. In doing so, Roth lay bare the cunning of history that accounts for the disparate fates of Jews living throughout the diaspora, and he also reclaimed these eradicated Jewish lives for the collective consciousness of an increasingly amnesiac culture.

As the 1970s gave way to the 1980s, conventional literary modes increasingly could not keep pace with Roth’s imaginative efforts to evoke Jewish life. And so he jettisoned these generic constraints. The Counterlife (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1986) would mark Roth’s most significant aesthetic leap. Here, he crafts a rigorous scaffolding to evoke the collision course of Jewish ideas that roil around the subjects of anti-Semitism, Zionism, Holocaust remembrance, the Palestinian issue, and the viability of Jewish life in the American and European diaspora. The novel’s five long chapters, or books, bristle against one another in essential ways, and several incongruous fictions emerge. In the first chapter, Zuckerman’s dentist brother expires during a risky cardiac operation; he then reemerges in the next chapter, abandons his family in New Jersey, and immigrates to Israel. In later chapters, the heart problems suddenly plague Nathan, and it is Nathan who dies on the operating table.

Mischievous Roth baits readers into locating the “real” fiction, into flipping back through the pages to figure out what’s what, until we ultimately realize that the labyrinthine structure of the novel—its collision courses and internal inconsistencies—trenchantly evokes the vertiginous fates, the internal clashes and conflicts, that have defined the Jewish ethos in these post-Holocaust years. If one cannot count on Roth’s characters to play by the rules, the ideas they force-fully express are certainly “real” enough. What are we at root, the novel seems to ask, but great and furious ideas made flesh? “The treacherous imagination,” Zuckerman contends, “is everybody’s maker—we are all the invention of each other, everybody a conjuration conjuring up everyone else. We are all each other’s authors.” And still one finds oneself caring for the lives of these most unreliable, most fictional of characters, so vividly and thoughtfully does Roth evoke his human subjects in page after page.

Given that we live in a culture that has supported multiple seasons of television shows like Fear Factor and The Apprentice, it is not surprising that most casual readers of Roth’s early work tend to remember the more scatological and caustic moments over the poignant ones. Mention Portnoy’s Complaint to ten readers and count how many of them segue into jokes about liver and masturbation. Yet, scenes of filial tenderness permeate Roth’s works as powerfully as those featuring various forms of rebellion. Indeed, the scenes of tumult depend upon these scenes of ineffable tenderness, and vice versa. These countervailing impulses imbue Roth’s characters with that requisite roundness that defines their and our humanity, and adds that necessary frisson of dramatic tension to the work.

When I think of Portnoy’s Complaint, I remember the outrageous moments, but I also remember Portnoy’s reflecting upon those “walks with my father in Weequahic Park on Sundays that I still haven’t forgotten. You know, I can’t go off to the country and find an acorn on the ground without thinking of him and those walks. And that’s not nothing, nearly thirty years later.” While outrageousness abounds in The Plot Against America (including, yes, a masturbation scene), the narrator’s recollection of the time when he mistakenly locked himself into a childhood friend’s bathroom resonates strongly. Roth infuses this apparently prosaic circumstance with great poignancy, as the friend’s mother, Mrs. Wishnow, soothingly advises a young, panicked “Philip Roth” how he might open the door and free himself. The tender counsel goes on for pages, until Roth’s friend, Selden, finally manages to shove open the jammed (but unlocked) door:

And that was when I began to bawl and Mrs. Wishnow took me in her arms and said, “That’s okay. Things like this happen. They can happen to anyone.” “It was open, Ma,” Seldon said to her. “Shhh,” she told him. “Shhh. It doesn’t matter,” and then she came into the bathroom and turned off the cold water—which was still streaming into the tub—and, without any problem she opened the closet door and took out a fresh towel and began to dry my hair and my face and my neck, all the while gently telling me that it didn’t matter and that these things happened to people all the time.

In this protracted episode, Roth evokes with stunning clarity the terror that occasions even the most ordinary of American childhoods, and the mother love that answers these summonses. Which is to say that the once prevalent view of Roth as a literary bad boy is every bit as impoverished an understanding of the writer’s achievements as the patrician image that now threatens to hold sway.

![]()

If it’s an image of Roth we must have, let’s see him in his two-room writing studio in Connecticut, poring over a trio of sentences that don’t quite hinge together in the manner he would like. This is an image that most likely captures the texture of Roth’s felt life, and one that might serve as a productive example for other writers. E. I. Lonoff, the maestro of Roth’s The Ghost Writer, offers a pithy description of his craft that would seem to apply to Roth’s own efforts: “I turn sentences around. That’s my life. I write a sentence and then I turn it around. Then I look at it and I turn it around again. Then I have lunch. Then I come back in and write another sentence. Then I read the two sentences over and turn them both around.” How else to explain Roth’s scrupulously crafted sentences?

I teach in an MFA program in creative writing, and while several of my students dream about being authors, few genuinely seem to enjoy being writers. Such enjoyment seems to them a luxury they cannot afford, given the hardscrabble literary and academic markets that await them. They work primarily, and doggedly, to achieve certain ends: securing that coveted book contract, delivering readings at book festivals, garnering thoughtful reviews. What I try to tell them (gently) is that most professional writers encounter far more indignities and disappointments along the way than rewards. At the risk of sounding sanctimonious, or downright depressing, I tell them that one must find one’s reward in the actual act of writing each and every day, in crafting that perfect sentence after a morning of fits and starts.

If you’re lucky, I say, a book will follow after many months, perhaps years, of labor. But completing a book—the kind worth completing, anyway—is a Herculean task (and one that Roth has accomplished over and over again during the past forty-seven years). For now, I tell them, just keep turning those sentences around.

Andrew Furman is chair of English at Florida Atlantic University. He is the author, most recently, of Alligators May Be Present (Terrace Books, 2005).